"It's kind of a Gesamtkunst work," muses Doug Aitken from his studio in Venice, Los Angeles.

The "it" in question is Lightscape—the artist's latest multidisciplinary undertaking. The project, five years in the making, is difficult to describe: "It's like a planet," Aitken continues, "occupied by music, film, narrative, and many tactile sculptural works made from foraged materials."

At the core of this "total artwork" is a feature-length film that unfolds like a lucid dream. Aitken takes as his setting miscellaneous landscapes of the American West—desert vistas, multi-level parking garages, Neutra houses, highway gas stations, and 24-hour donut shops—staging cryptic encounters between people (including the likes of Natasha Lyonne and Beck), wild animals, and the built environment. "I like this idea of embracing the world as a sprawling, hallucinatory space and not trying to make sense of it," Aitken muses. Tensions build, but questions remain unanswered.

The project is the result of pure exploration for the 56-year-old artist, who was working pre-pandemic on a Philip Glass-inspired "minimalist song cycle" when he was approached by the Los Angeles Philharmonic to collaborate on a mixed-media work. Lightscape took shape from there, with Aitken's vocal compositions brought to life by the Los Angeles Master Chorale, accompanied by the Philharmonic under Gustavo Dudamel. This captivating sonic collage propels a tangle of narratives forward, eschewing conventional dialogue in favor of language so sparse it feels abstract.

Those curious to learn more will need to witness its debut for themselves, first on Nov. 16 at the Los Angeles Philharmonic, or later in its second iteration at the Marciano Art Foundation from Dec. 17 through March 2025.

Ahead of the work's premiere, Aitken sat down with CULTURED to talk about the genesis of his ambitious undertaking—and when he knew it was finally finished.

CULTURED: Lightscape will premiere with the Los Angeles Philharmonic. You will screen the film alongside a live score. Then, the work will go on display as a multi-screen installation at the Marciano Art Foundation. Which is the primary, intended format of this work—live performance or video installation?

Doug Aitken: There really is no intended format. It seems to me that the art world isn't really about embracing change—it's about stasis. You make the work, you show it, and it goes off somewhere. Often, the artist has no idea where it goes. That system needs to evolve: Art should be allowed the chance to be more liquid and mercurial.

CULTURED: What was the genesis for the project?

Aitken: About four or five years ago, I decided to write a minimalist song cycle that would lean into this idea of the future, the space in front of us. Like, How are we inhabiting the landscape and the ecology as we move forward? I thought, It'd be really interesting if I could use a human voice to explore this. I found myself looking at some of the uses of language that are very reductive, like Samuel Beckett, or Bruce Nauman, or Joan Didion—people who reduce language to these little electric haikus. I started developing these sonic poems, and then I began to bring in singers.

CULTURED: How did the Philharmonic get involved?

Aitken: I got a phone call from them. They said, “We like your work. We'd love to collaborate, do you have any ideas?” I said, “Well, I'm kind of writing this piece about this liminal frontier, why don't we develop it together? Maybe we can make it a film and an installation?” I started seeing it as less of a sound work, and more as a planet of narratives and stories.

CULTURED: Of all the elements in this "planet of narratives," I imagine the film will be the component that is most widely disseminated, or most accessible. How do you feel when one facet of a work comes to represent it in its entirety?

Aitken: I don't really know—in this case, I'm not finished yet. But I do see it as a work that will exist in many iterations. The version that we're launching at the Philharmonic is about live human performance, accompanied by this filmic narrative. The second iteration is more immersive—there will be seven screens, so it's an architectural environment that you fall into. We're working on a third iteration, too.

CULTURED: What makes the West a particularly fruitful place to explore these ideas about the future and our reality?

Aitken: Despite the control that we superimpose on our culture here, we live in a very feral landscape. There's a lot of diverse energy, culturally and geographically. I find myself constantly exploring, trying to rediscover places I know well, only to find that they've transformed completely—seemingly overnight. That vision of the West—as feral and ever-changing—is hugely important for me creatively.

CULTURED: So much work has gone into this project. It seems you didn't have a specific vision for how it would turn out—how to you keep your cool when there's so much riding on your work?

Aitken: I feel very at home in environments that are improvisational. I feed on that condition in terms of artmaking. For example, we filmed the video work over six months—it wasn't a few weeks. We spent half a year just… out there. You can't really script something like this, because it doesn't have much dialogue or traditional scenes. I'd say, “There's going to be 10 narratives, and they're going to be occupied by different characters and different music will propel them.” But at a certain point, we'd gone past what we'd planned, so there was nothing to do but to keep going. At that point, you're at a Days Inn in Death Valley, it's 2 in the morning, and you're scribbling a scene on a napkin. At 6 a.m., you meet everyone in the parking lot and you just go make it.

CULTURED: How did you cast the actors in the film?

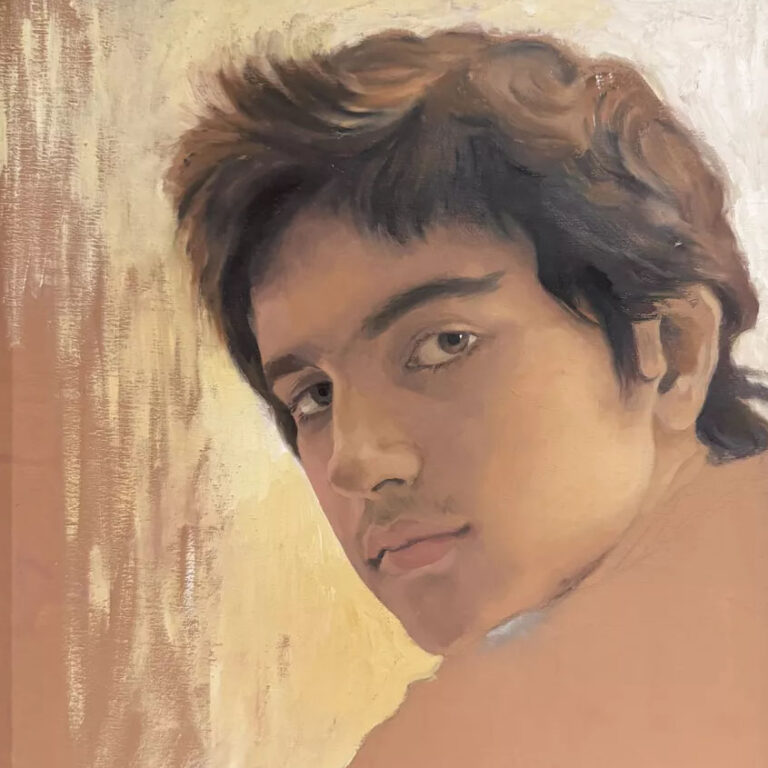

Aitken: It wasn't highly cast. Natasha [Lyonne] is just someone I knew. Another actor in it, Joanne, has been in several pieces. I found her sitting on a tree stump drinking a coffee like 10 years ago. Nikolai Haas ended up in it because we ran into each other at something, and I just asked him. Beck is a lifetime friend and collaborator. He's in this 2 a.m. scene at a doughnut shop in the valley. It's totally unscripted—one thing leads to another. I like this idea of embracing the world as a sprawling, hallucinatory space and not try to make sense of it. Some great filmmakers throughout history have done that, like [Jean] Cocteau with Orpheus or [Robert] Altman with Nashville or [Alejandro] Jodorowsky with El Topo. They totally abort traditional logic, embracing something that's more intuitive and stream-of-consciousness. In the end, we absorb it in the same way.

in your life?

in your life?