Alexandre da Cunha is a master collector and manipulator of everyday objects, from shovel handles to ping pong rackets. Taking inspiration from art-historical movements like Arte Povera and Tropicália, he turns found tools and knicknacks into sculptural poetry. His goal is nothing more—and nothing less—than to bring himself and his audience into the present moment.

Da Cunha’s latest exhibition, on view at James Cohan in Tribeca through Dec. 21, includes large-scale sculptures, new “Vitral” works, and a series of “Ikebanas” inspired by the namesake Japanese floral arrangement—but instead of flowers, the whimsically bent elements are bottle brushes, broom parts, a glass bottle, a drain, and so on. He finds every element of his sculptural collages between the United Kingdom and Brazil, the two countries where he works.

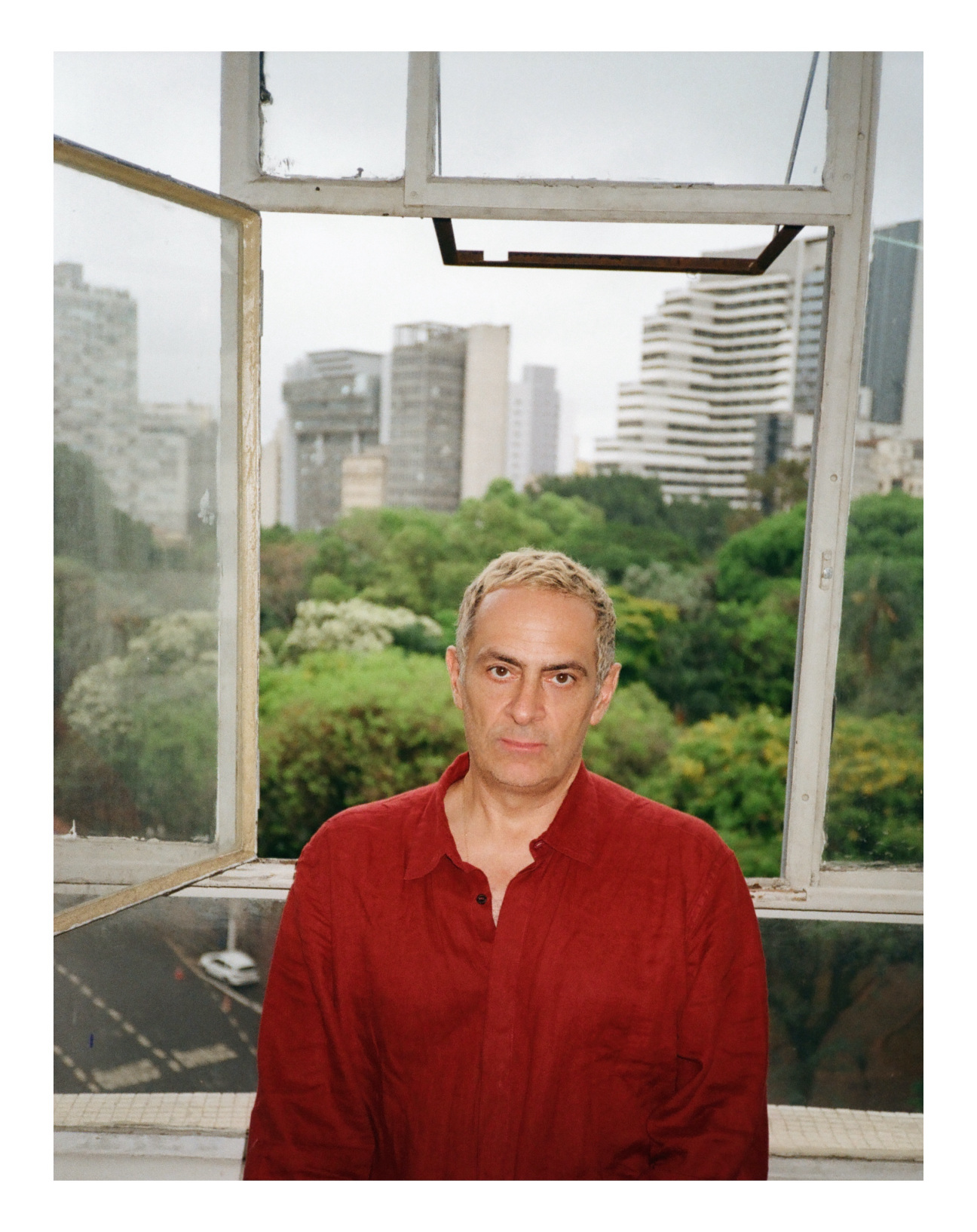

“My work is an invitation to the viewer to slow down and fight that anxiety of being in between the past and the future,” da Cunha says. “The materiality of the work functions as a reminder of the present time.” The artist caught up with CULTURED to discuss how his itinerant lifestyle fuels his work and why young artists should worry a little bit less about their futures.

CULTURED: The title of your latest exhibition, “These Days,” has a mundane yet dreamy undertone that seems to pervade a lot of your work. Where does it come from?

Alexandre da Cunha: “These Days,” to me, refers to notions of time. I feel that my work and my relationship with materials is somehow a call for the viewer and myself to be present and aware of things that surround us right now.

These Days is the title of one of the “Exile” works in the show. I have been developing a series of works on A4 paper over the last couple of years, and they seem to work well in contrast to the more formal, large-scale sculptural works. I sometimes make them at home or when I am traveling, and I really enjoy how portable and straightforward they are. But they are also confessional and funny, as if they were pages of a diary or chapters of a dreamy narrative.

CULTURED: Your work is in dialogue with historical movements, such as Arte Povera and Tropicália, that go against the grain of mainstream art. Why did these movements initially speak to you, and how do you relate to them now?

Da Cunha: Both movements played a massive role in my work from the beginning. They combine radicalism with poetry through the use of simple and mundane materials. When I use cleaning mops, I am referring to the softness of the material and the relationship to textiles, but also the social aspect of labor and trading embedded in them. The other common point [with these movements] is the relationship with everyday life. My work doesn’t exist without me being outside the studio, seeing street markets, traveling, relating to other people and other environments.

CULTURED: Could you elaborate on some of the everyday “throw-away” materials that serve as recurring subjects in your work, like bottles, brushes, keys, belts? What do these objects mean to you once their functionality is stripped away or transcended?

Da Cunha: The core element is curiosity. I start by being intrigued by an object and how it is made, designed, traded, and so on. My studio is a sort of laboratory of objects with a lot of studies and experiments going on. From there, it is about investigating these objects and their movement, highlighting them by doing a gesture where some elements are combined together. The most economical gestures are usually the most successful. I often feel that my work as a sculptor is almost invisible—I don’t do much with my hands directly onto a material.

The objects have a lot of baggage, and that tension between my initial idea and their personality is the most essential part in the construction of the sculptures. It is a dialogue—sometimes a bit of a fight. My role is very similar to a choreographer or a film director, and I have to listen and pay a lot of attention to those players in the game. It is an endless negotiation.

A lot of the objects I use have a clear relationship with the body and the domestic. In the recent series, “Ikebanas,” I used a lot of materials that I lived with for a long time; I combined them as if they were random words being placed together to form a sentence, but they seem to be always talking about the same subject: the body.

CULTURED: How has living in both Brazil and the U.K.—navigating between these two worlds, cultures, landscapes—shaped your art?

Da Cunha: I grew up in Rio de Janeiro, lived in a few places in Brazil, and spent half of my life in London. Now I am moving back to São Paulo and pretty much sharing my time between places. Being in transit has a lot to do with my practice. I find my materials and references when I am moving around.

At this point, I might be ready to be more settled in one place but I feel that my work is constantly pushing me not to stop, not to accept, not to commit to a specific place or culture. It can be quite disorientating at times. I often feel that I don’t belong anywhere, but I do think the work grows as it travels and the flux of ideas and things in general inform the work in a positive way.

CULTURED: The “Exile” series features gouache paintings without glaze to facilitate a direct, unfiltered relationship with the viewer. What is your relationship to gallery spaces? How can it be institutional but also a private, intimate space between artist and viewer?

Da Cunha: The decision to not frame these works was an attempt to make them more vulnerable and look more like an object, rather than a precious picture. There is a certain ambiguity between them being an object and an image. It was very liberating for me to carve out space for them and make them look as relevant as the large-scale works. More generally, I think my work refers to this tension between public and private, soft and hard, intimate and monumental. I have been trying to make this shift between spaces, trying to make a gallery feel like a museum, a public sculpture feel like urban furniture, and so on.

CULTURED: What advice would you offer younger artists? In particular, how would you advise them to seek inspiration from everyday life?

Da Cunha: I have been doing some teaching and have a lot of contact with younger artists both in São Paulo and London. Young artists seem to worry too much about a career and end up avoiding taking many risks. They try to have too much control, and that can easily go wrong. It took me a long time to understand and see my practice as a separate “being” that I actually don’t have much control over. The secret is to be together with the work, follow and trust it.

in your life?

in your life?