Welcome to Provocateurs at Play: a new column from CULTURED’s Style Editor-at-Large Jason Bolden. The preeminent stylist and creative director has earned a reputation as a conscientious interrogator of the fashion world's norms and expectations—working with the likes of Nicole Kidman and Michael B. Jordan to create intimately researched and refreshing moments that keep us hungry for more. This new series of conversations, spotlighting enduring talents from across the industry and beyond, promises to be no different.

“Whenever I take a moment and look out, there are artists like Samuel Levi Jones whose works invite me to shift lenses and dig deeper,” says Jason Bolden. His words speak to the core of Jones’s practice—one that finds clarity in dismantling the seemingly immutable.

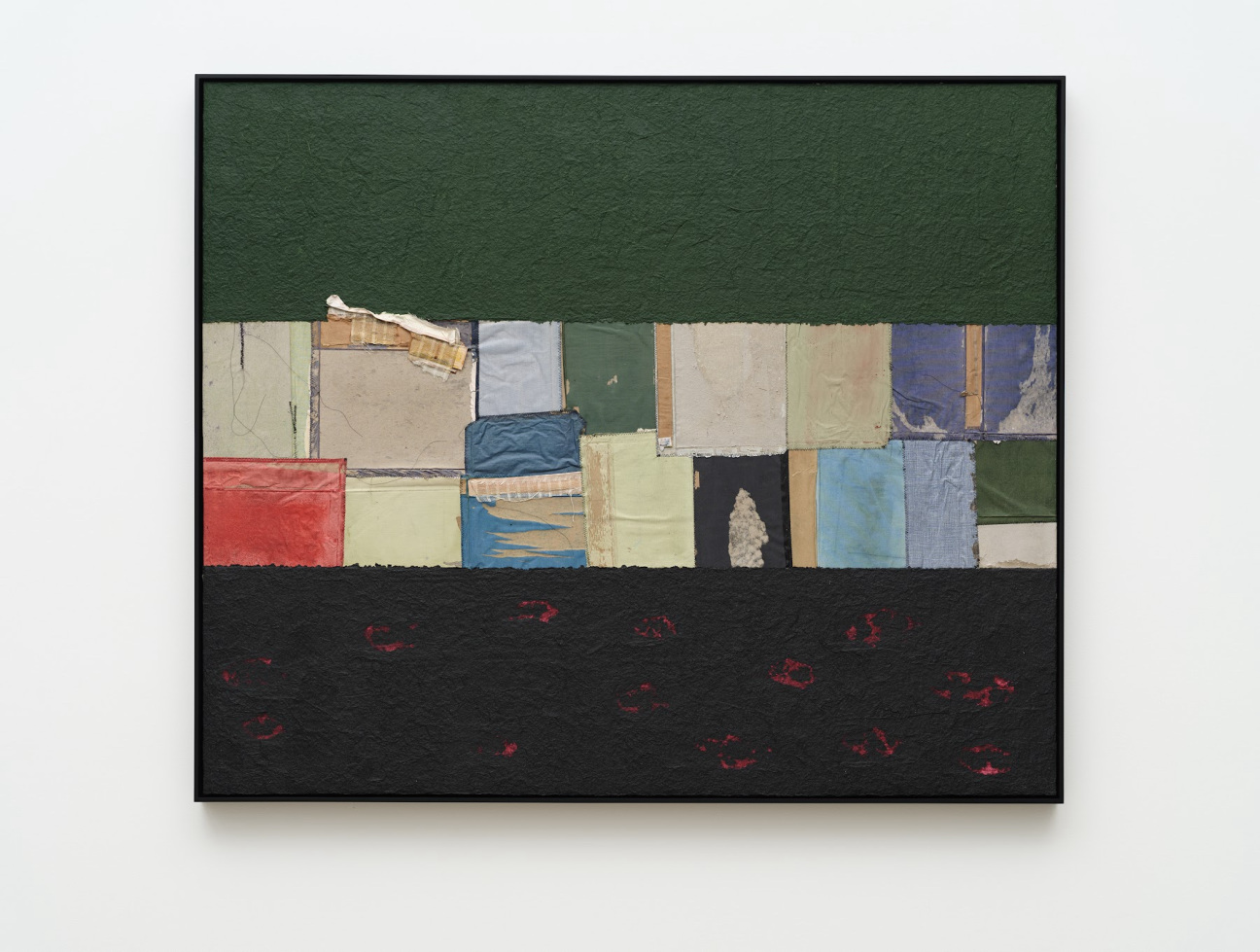

Jones’s work, particularly in his new exhibition "abstraction of truth" at Vielmetter Los Angeles, operates in this realm of deconstruction. After dissecting symbols of authority—law books, encyclopedias, and national flags—he reassembles them in configurations that interrogate the colonial narratives they’ve long upheld. The exhibition, on view through Nov. 9, is both a call to action and a confrontation, urging viewers to question the truths they’ve inherited.

In their candid conversation below, Bolden and Jones delve into the “beautiful accidents” and “divine moments” that guide their presentations. Art’s greatest revelations may not come from precise planning, but rather the spaces left open to the unexpected—a testament to the transformative power of letting go.

Jason Bolden: There so much I’d like to talk about so let's dive in. Was there a defining moment in your life when you knew you were an artist?

Samuel Levi Jones: It was toward the end of a photo class I took in undergrad. I shifted from thinking I was just an athlete, to knowing I was something else. Growing up, I played various sports, and in college, I played American football and ran track. In the summer of 2000, some of the team took a trip to Europe. We played a couple of exhibition games, and that was my first time overseas and the first time that I ever flew on a plane.

I was in college and had a point-and-shoot camera with me. We were there for nine days in the Czech Republic, Austria, and Germany. It was a very, very tight schedule. We had maybe two hours of downtime the whole time. I took a dozen rolls of film, so a little over a roll of film a day. That was my way of seeing things. I took a photography class, and everything about it just made sense. I wasn’t the best student. I don’t retain and regurgitate information very well. But I was in this class where you could get hands-on experience, and I was just excited about doing something in school that I was actually good at.

Then, there was a period from about 2000 to 2006 where I worked a couple of different jobs with the mindset of going back to school. I eventually went back and got a BFA in photography. At that point, I had an amazing instructor who encouraged me to apply for grad school. She envisioned me teaching, which I haven’t done yet but had considered before. I was actually considering applying for a job for a few nights, but I didn’t. But from that point all the way through grad school, a lot of my making was in academia.

Bolden: So you still hadn’t really focused on the idea that being an artist could be a job where you could make a living and have a career?

Levi Jones: I didn’t! Even in grad school, I was really just focused on what I was doing. I made 48 portraits which are now on display with [Gerhard] Richter’s portraits in Dallas. I remember coming back for my final semester of grad school and one of my classmates was complaining about grades. It was after winter break and well into January. I told him, you know, I never even really went online to look at my grades. I wasn’t there for the grades. Grad school was the first time I had a studio, and I was fully into it. I knew nothing about the art world. I’d maybe been to New York one time. I was in a group show at the Watts Towers [Art Center] in LA, where I met Mark Bradford. He invited my family and I to his studio that evening, and we spent several hours talking.

Bolden: That’s a beautiful introduction! That’s a huge introduction!

Levi Jones: Yeah, it was insane! That was in late August of 2012. Then in October, Mark had an exhibition at Sikkema Jenkins. He invited me to come to New York and hang out. I was in New York for a little over a week and went to a couple of different things. That was my introduction to the commercial art world for all intents and purposes.

Bolden: That's wild. A lot of us, myself included, started out in the same kind of world. With things like art or fashion, you never really know if it can really be a full-time job. I never understood that this was a possible career. When I thought about fashion, I only thought about two kinds of people: people who work in retail, and designers. That’s really what I thought the business was. It’s amazing to hear you talk about this and understand that the throughline for most art is people standing in the exact same space of not really having an idea of what it can be. It all becomes this beautiful accident. And then you see someone like you!

Sometimes I look at your work, and a lot of the abstract stuff, and it’s like, Could this be a perfect, beautiful accident? Oftentimes I have an idea then I’m in the middle of styling someone and I’m like, “Oh this is it! I’m done!” When I look at your work, I think the exact same way. Did he just stop? Or did he just think that he could keep piling things on?

Levi Jones: Using the word accident is interesting because there are these sort of divine moments that happen. When I discovered that Richter’s images were sourced from the encyclopedia, I realized that those books were unintentionally from the same years that he first showed that work in Venice. It was like the universe spoke to me in that moment and told me that this was the path I was supposed to be on. Also in that moment, before the work even started to come together and I figured it out aesthetically, I wanted it to be shown with Richter’s.

Bolden: Sometimes the shoe just fits. It's not just an “accident,” but feels like it was meant to be in that space. Sometimes the body, mind, and eyes just connect in those moments, and you find those perfect “accidents,” if you will. How did you jump into really honing in and focusing on the African-American experience in your art?

Levi Jones: That comes from my upbringing, my familial experiences. I grew up in the Midwest, outside Indianapolis.

Bolden: Oh that’s right! I grew up in the Midwest too, in St. Louis.

Levi Jones: Growing up in a small town like I did is interesting in the sense that a lot of people know each other. I never had issues with law enforcement. In fact, one of my father’s ex-girlfriends was a police dispatcher. So I remember one time I was pulled over and I was let go. I heard about it from my dad a few days later.

Bolden: Maybe in some cases, it isn’t the best scenario. And, sometimes it can be the opposite.

Levi Jones: Yeah definitely. When I lived in Indianapolis for the first time, from 2002 to 2010, that’s when I started having different experiences. I was like, “Oh, shit.” It really hit me playing football in college, at a predominantly white Christian school. There were covert acts of racism on the football field and in class. Interestingly enough, I was recently invited to participate in a group show there. And I’m gonna give them something heavy.

Bolden: As you should!

Levi Jones: I told Mark Bradford about it, and he said, "Someday you'll be invited back, and you can tell those coaches what you really fucking think."

Bolden: There’s a similar thing in my business. When I first started, people would say no. They wouldn’t always have a reason, they’d just say no. But eventually you’re in a place where you can say no to people, and even tell them why to their face. I think what draws people to your work is the heart and the story behind it. It's done in a very beautiful and abstract way. That's part of the magic of your art—it is a constant study and teaching. Not everything is on the surface, and it’s nice to jump into a world with a little more cultural depth sometimes.

Levi Jones: I think we exist on the surface too often. If we want to get to the root of things, we can’t stay on the surface.

Bolden: With social media and all that access, do you think the purpose of art has shifted?

Levi Jones: I think so. Social media brings things to the forefront visually. It’s right in your face and you can't ignore it. You can’t say, “Oh, I didn’t know.” Of course, there are downsides, but it depends on what you use it for. It has created a space for deeper consciousness. It at least provides the opportunity for that.

In terms of my making and being in these spaces and being around other creatives, it really opened my mind up from seeing things on the surface. I used to watch mainstream media, but I don’t consume that anymore. Now, with social media, it allows access to things that are happening below the surface.

Bolden: So true. I’ve always wanted to ask this question; it just popped into my head. Do you ever find it hard to let go of your work? You’ve completed a piece and were like, “I can’t let this go?”

Levi Jones: There's one work I wish I had back, but I don’t think about that unless someone asks.

Bolden: I guess you’re starting in a place of creating this art to live in different places so more people can experience it. But, in my head, I see you spending so much time with a piece, all that goes into finishing it and then finally when it’s done, you just turn it over? That’s wild.

Levi Jones: I can explain why. When I was taking photography in undergrad, I had this instructor. First of all, I had no idea what I was getting into. I had no idea I had to take three semesters of drawing, I freaked out. I had some time before the program started, and I started drawing.

I got through just fine but I had this professor who helped me merge the ideas with the making. When I played college football, at any given time there were usually no more than three non-white players on the team. They did everything they could to keep us off the field. I kept having these recurring dreams about a different scenario where they excluded me. It wasn’t until I left Indianapolis for California that I stopped having these dreams. So, for me, art became a medium to share those stories and create spaces for conversation. If the work doesn’t leave, that conversation can’t happen.

Bolden: Maybe there’s part of me that’s just being selfish. It’s so profound to see it in that way. In order to have these stories exist in different places, you have to release them. That way, they can spread to more and more people and keep the conversation going.

Levi Jones: Exactly. There's a sharing and giving that goes along with it as well. The message can’t go out into the world unless the object leaves.

Bolden: My grandmother used to say all the time, "If a person keeps their hands closed, nothing can go in and nothing can come out." It kind of speaks to that. If you hold on to the story, it stays confined, but when you release it, it can impact others and shift things. Are you excited to explore new mediums, or is this your world and your wheelhouse right now?

Levi Jones: I’m working on a public project that I’m really excited about. At first, I thought it would be a one-off thing. But there are so many other stories involved. Recently, I’ve been thinking about expanding it and doing projects in other towns. Growing up in my small town, I had little access to the arts. I’m thinking about young people in the community and what this project could mean for them. It’s a working class town, and a lot of people play sports. The town is in a lot of decay, like many industrial towns were. I have no idea what will come from it in terms of opportunities, but I’m excited to give people a different perspective on the world. Going back to what we were talking about earlier with making a career in art, there are so many things we can do that bring pleasure in life.

Bolden: I love how you simplified it. It makes me want to live in that space and simplify things as much as possible. Just like how the best meals are often made with only a few ingredients, some of the most impactful things are the simplest. I think you can look at art and life in a similar way. I have to ask because it's interesting and people always ask me this. Who is the one person on your list that you would say, “I personally like to collect that person’s work”?

Levi Jones: Wow. I won't give a particular name, but I can say that a lot of my collecting has been through artist trades and are with people that I have a connection to. And it's interesting because it doesn't happen simply. There are so many times where you engage with an artist and be like, “We should trade.” And it never happens. Then you're sort of always revisiting that topic of trading. So, there is something to be said about that.

When you spoke about being in your own space all the time and having your blinders on, there's something to be said about when you get to that point of making it actually happen. It's like in the same way with you and I having this conversation, like we've engaged a little bit before. We have so much going on. Now we've gotten to the point where it's like, “This should happen.” So it's really about, for all intents and purposes, the connection that happens and the objects that you exchange. There's a token of that connection that exists.

in your life?

in your life?