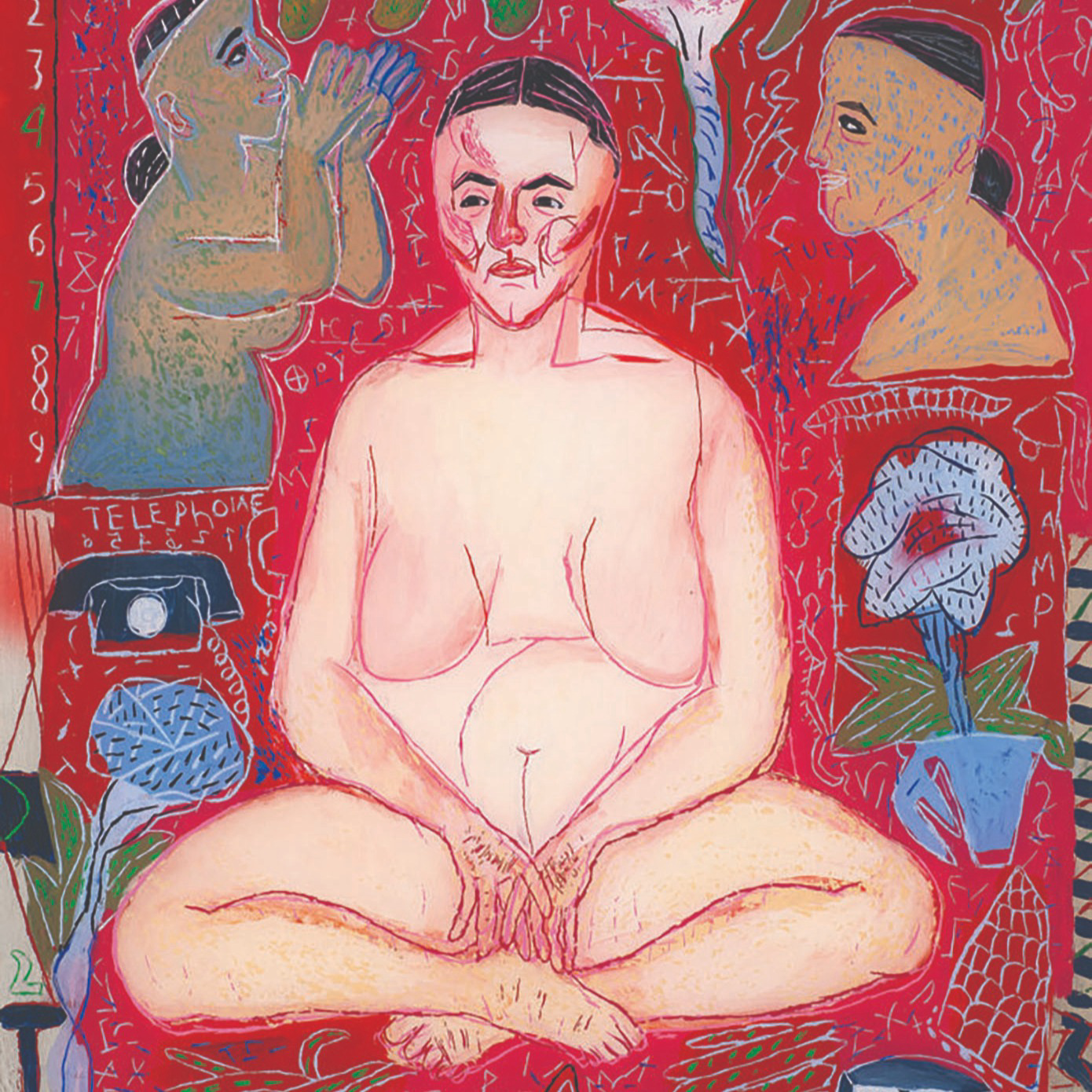

Over the past decade, Meriem Bennani has filtered the crushing estrangement and feverish pace of postmodern life through a delirious yet distinctly earnest lens. Topics as disparate as immigration, girlhood, and the aftershocks of colonization in the Maghreb surface in the artist’s work, which can take the form of a scrappy reality TV show or a spinning tornado powered by electric bike motors.

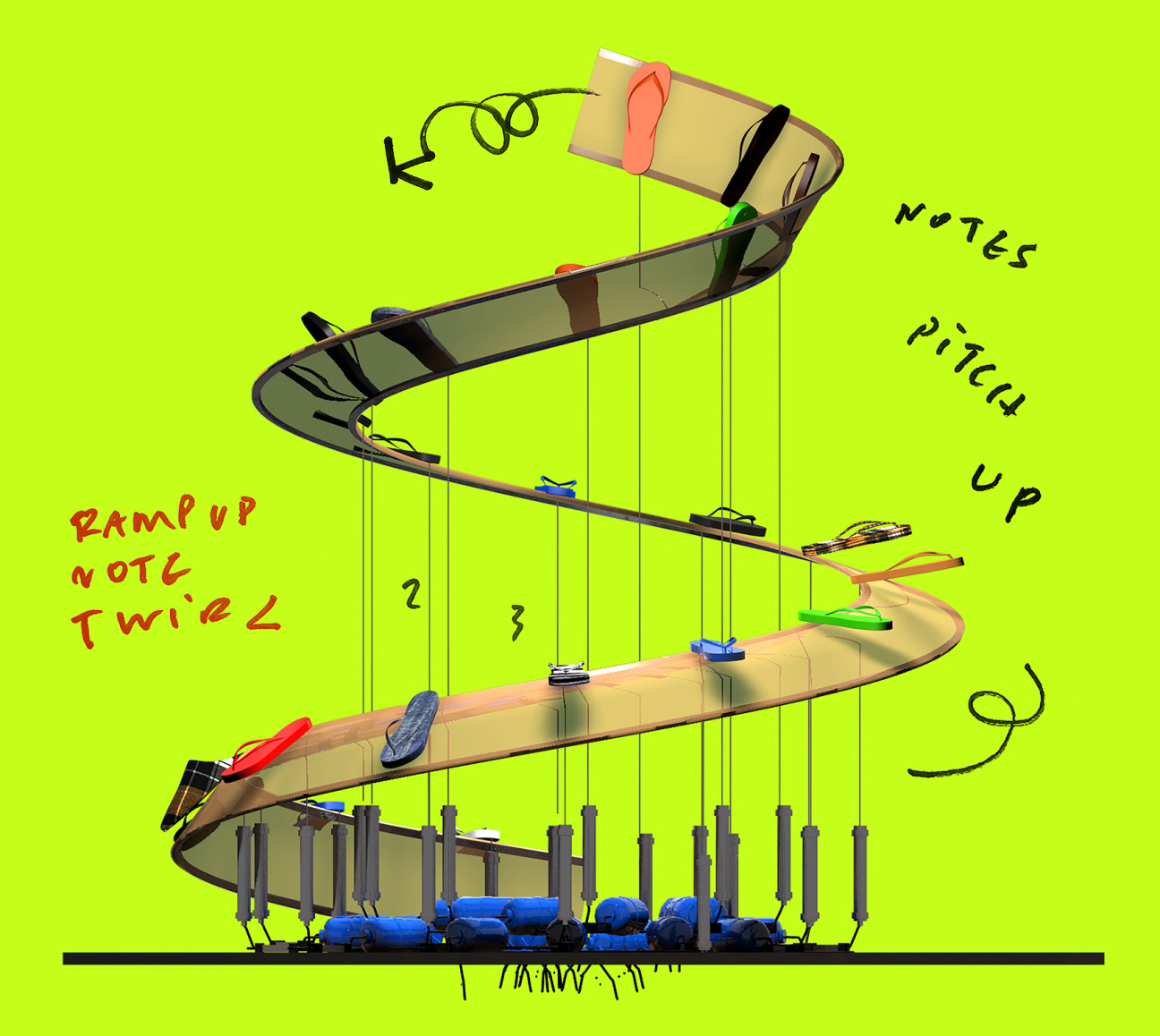

“For My Best Family,” a new exhibition opening Oct. 31 and commissioned by Milan’s Fondazione Prada, is Bennani’s latest world-building exercise. On the ground floor, a soundtrack composed with Cheb Runner will accompany hundreds of flip-flops in a trance-like ballet. The mechanical installation, titled Sole crushing, promises both cacophony and catharsis. Above, visitors will be able to take in the artist’s most ambitious film thus far, For Aicha. Directed with her longtime co-conspirator, documentary filmmaker Orian Barki, and with the support of animators John Michael Boling and Jason Coombs, the work follows Bouchra, a Moroccan jackal living in New York, as she attempts to make a film about how her queer identity has shaped her relationship with her mother. Below, Bennani and Barki give CULTURED a peek at the film and exhibition’s backstory.

CULTURED: For Aicha, the film included in “For My Best Family,” is the longest video project you’ve ever worked on. What challenges and opportunities did the extended format bring?

Meriem Bennani: When you make a movie over two years, you’ve gone through so many different political and personal moments. You have to sustain some kind of narrative cohesion while going through so much. You also have to maintain spontaneity. The story [is] about a mom and daughter learning to understand each other around queerness. The thing is, it can so easily fall into something so annoying in terms of a coming-out story in the Arab world.

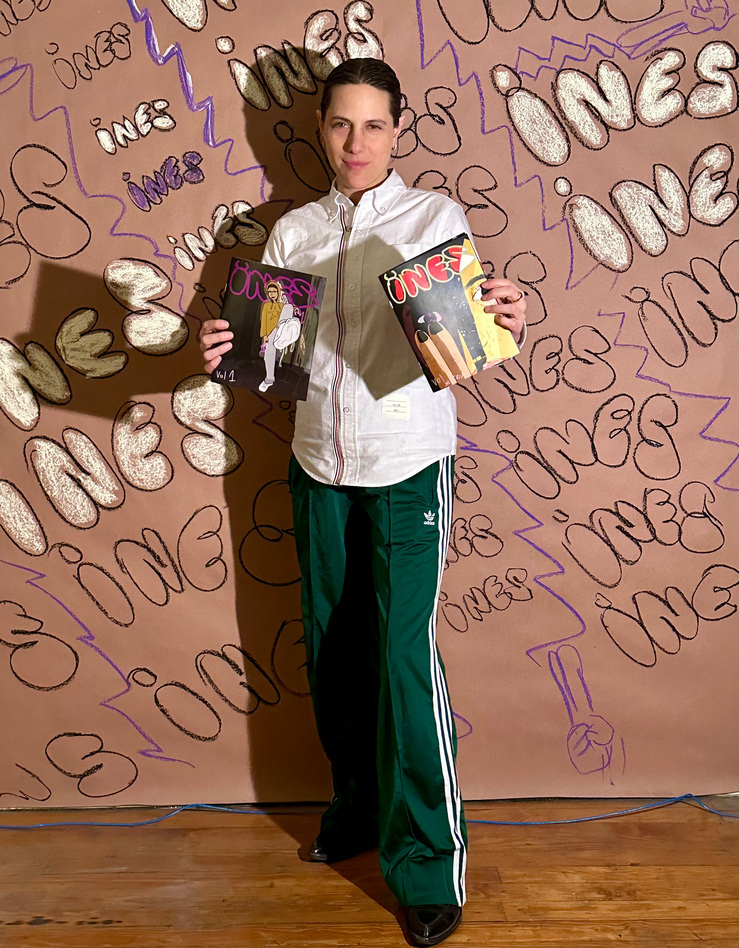

People in Western countries, maybe that’s all they ask for—to see how it’s so hard to be Arab and gay. We were scared to fall into that, but at the same time we thought it would be cool to have a fun and emotional lesbian story about this Moroccan filmmaker who lives in New York... What we found as a solution is specificity, which is realizing that maybe it’s a documentary about me and my mom in a way, and it doesn’t matter what it means because it’s so true to us.

Orian Barki: Meriem was like, “I feel that we’re missing the perspective of the parent in the relationship. Maybe I should call my mom and ask about her experience, and we can use that as inspiration.” So she called her mom. They’ve had conversations before about Meriem’s queerness and their relationship, but never like this. After the call, [Meriem] played the recording to me and translated it live.

Bennani: We were like, “This is better than everything we’ve been trying to write. We have to use it as the spine of the [film].”

Barki: So we created this meta layer for the story. On one level, it’s about a daughter trying to understand her mother better, to be able to have some type of closure and move on, but on another it’s like, “I need to understand you in order to be able to make this film.”

Bennani: I was really uncomfortable making a film about myself or bringing my mom into it. She’s always accepted being in my films, but that doesn’t mean she accepted making it about us, especially about the most sensitive part of our relationship. I’m really impressed by her. Giving me this was a mix of love for me, but also an understanding that I need it, which she says in the film.

I also want to say that a very important step was to fictionalize things: This is not my mom anymore. It’s re-recorded with Moroccan artist Yto Barrada’s voice. Departing from things in that way allows you to look at it like a story ... What Orian and I have in common is we know when something feels true. It’s a balance between a certain tenderness and humor that is not trying to be cool or relevant—it just is. That’s our compass.

Barki: Sometimes it was just about going on our phones, looking for videos of moments, and then reproducing them in a fictionalized way. The scene in For Aicha where she gets her ear pierced and then puts the sunglasses on to hide her emotions—we have a video of when I got my ear pierced and Meriem made fun of me. She was like, “Are you crying?” You can take those real-life moments and place them in a way that feeds into an emotional arc. That’s another way of keeping this documentary spirit, with these small poetic life moments.

CULTURED: Meriem, what was it like to work on Sole crushing at the same time as For Aicha?

Bennani: With Sole crushing, it was fun to create an environment that is not telling you a story but that hopefully generates a feeling within you. It’s an overwhelming, loud installation. It is definitely informed by going to protests. It’s about being surrounded by a big group of people [united] around one thing—what that feels like. It’s also about moments of collective catharsis—not necessarily just around politics, but also around musical traditions. It’s more about the essence of living than a specific person’s story.

CULTURED: Why choose flip-flops as your protagonists?

Bennani: The Fondazione Prada space is so gorgeous and fancy. It felt like a challenge to be like, “In this insane space, I’m going to work with a flip-flop. How can I go from silly to monumental with such an unprecious, bottom-of-the-fashion-chain thing?” That was the initial impulse. Because I wanted to make music with flip-flops, I started researching percussive dances, like tap dance and flamenco. I started getting really into flamenco and duende, [an elevated state of emotion often associated with flamenco]. Duende is anchored in a kind of tragic swag; it doesn’t matter how good you are technically, it just comes out of you. In the way it’s described by [Federico García] Lorca in his text on duende, it comes from the feet. And I grew up going to these spirit ceremonies of Gnawa music where you ask for the spirits to come [possess] your body. You have to take your shoes off so they can inhabit you because they come from the ground.

CULTURED: You’ve worked together for years now. Did you learn anything new about each other through this project?

Barki: I work with doubt as a guide, which can be a very annoying thing, but I use it as, like,“Oh, is this good? Is this not good?” Meriem is the complete opposite. We’re able to complete each other in this way where she has an idea and runs with it. And I’m always like, “Wait, I don’t know.”

Bennani: I’m more visually uptight. I’ll care about more within a scene, and sometimes I can get lost in that. Like, “She can’t be wearing those pants, she already wore them. They need to be blue.” Orian is always looking at the bigger scale. It’s like, “Who cares about if this shot looks good. First, the story needs to work.” But then we also need the shot to look good sometimes, because it does do something to the story.