Welcome to The Big Picture, where CULTURED’s critics zoom out for a wider view of the art world. While reviews remain the focus of The Critics’ Table, this space is reserved for longer reflections—treatises, prognostications, diaries, and meanderings. Really, anything goes. For this second installment, Co-Chief Art Critic John Vincler sifts through the messes of the current New York scene.

At the Whitney, “Edges of Ailey” crowds 18,000 square feet of gallery space with objects across media, from paintings and sculptures by other artists, to Alvin Ailey’s own archival notebooks, as 18 screens of moving-mage work loom over the exhibition. The show moves between cacophony and rhythmic polyphony, turning the multitudes into a chorus. Over in Kings County, “The Brooklyn Artists Exhibition” similarly invites chaos with its more than two-hundred contributors at the Brooklyn Museum. Amid the mind-spinning eclecticism of Thomas Schütte’s MoMA retrospective, visitors confront, in Lager (Storage), 1978, numerous painted panels, leaning casually against a wall. And in the kindred Mohr's Life, 1988, Schütte enlists a drying rack hung with numerous colorful socks.

The teeming, the too much, the disposably commonplace, and outright trash—mess seems to be the go-to riposte for what, often in today's New York gallery scene, feels like a retreat into pretty, clean, and conservative work. But not everyone can make disarray sing.

At Greene Naftali in Chelsea: A projector with a cap covering its lens, ladders, large sheets of cardboard on the floor pushed against the wall as if to protect the ground while painting (but with no sign of any actual painting), buckets full of paint tubes, a roll of pink foam wrap standing vertically on its spool’s end, numerous folding tables throughout, a couch, a glass jug of turpentine, an upright vaguely human-shaped figure wrapped in quilted moving blankets; old print copies of the New York Times; Manhattan Mini Storage moving boxes in various sizes; a blue inflatable exercise ball; industrial metal sinks detached from any plumbing; a compact refrigerator; a basketball; prepared and stretched but unpainted canvases grouped by like-size; and a working Harko brand clock resting on the floor still ticking. All of this sprawling stuff is clearly the contents of an artist’s studio, now presented in the gallery’s ground floor space.

This workspace-as-art is the work of the New York-based, 70-year-old German artist Michael Krebber (born the same year as Schütte), who may be best understood as a conceptualist concerned with how the ghosts of abstract painting continue to haunt art today. At the gallery, I am handed a postcard of Krebber’s actual studio, now empty, because the contents are, through Oct. 26, right here. As artists’ studios go, this is a particularly unaesthetic one: a jumble in need of an assistant with an organizational kink. From what I could discern, there are no finished works (at least, no finished paintings). The tools to make art are present, but the artist’s labor isn't.

I headed a few blocks south to Peter Fischli and David Weiss’s straightforwardly titled exhibition, “Polyurethane Objects,” at Matthew Marks. With its scattered, lived-in feel, and concern with mundane items, the show might seem to pair perfectly with Krebber’s, but, while their subjects align, the effects they produce are starkly different.

At Matthew Marks, it seems impossible that all of the objects in the large gallery are of carved and hand-painted polyurethane. Approximately 300 of these objects, facsimiles of common items found in the artists’ studio—from shoes to cigarette butts and tools to kitschy figurines—are clustered into tableaus, with these constellated throughout the space. Each arrangement strikes a delicate balance between the haphazard and the just-so. Most contain a deliciously deadpan pop element, where the artists have painstakingly reproduced the packaging of a particular, though dogmatically unremarkable, consumer product. Take, for example, the blue and red screen-printed design on the cube-shaped corrugated cardboard box of a 75-Watt Servistar spotlight bulb package (with a color scheme that closely echoes and recalls Andy Warhol’s 1960s Brillo boxes).

The show invites playful, close scrutiny of the objects. Again and again, I found myself asking in delighted disbelief: This too is made of polyurethane? Try to spot the dog-food bowl with several pieces of kibble in one corner of the gallery. This and even the wooden boards and boxes, the pallet, the chair, and the tire are all made of the polymer. Only rarely, particularly with metal objects, like a pair of pliers, did I find the copies unconvincing, but this glitch added an uncanny jolt to the awe inspiring effect of the whole. The exhibition also serves as an archive of the artists’ collaborative labor, with this particular body of work dating back to 1982.

Further downtown, in Tribeca, at Andrew Kreps Gallery, He Xiangyu presents a series of objects scattered, albeit very elegantly, on the floor of the gallery, in arrangements suggestive of urban architecture, a construction site, or a child’s make-believe world. The sculpture Hazy Windows, 2024, evokes an imagined spaceship, the components laid out on the floor in a loose approximation of the completed object before it is put together. The parts are made of ceramic or cast aluminum, with the exception of a few found metal elements (of galvanized iron and tungsten wire). He lives and works in Jingdezhen, China, where a millennium of tradition informs local ceramic production. His conceptualism smuggles in a deep engagement with the history of clay-based art through his seductive geometries of crafted objects. The work is immensely satisfying, evocative of minimalist sculpture. And it’s only messy when you consider He’s use of unpredictable materials like molten aluminum, and his sculpture’s relationship to more rigidly-ordered precursors, like the coldly formal floor sculptures of Carl Andre in the 1960s.

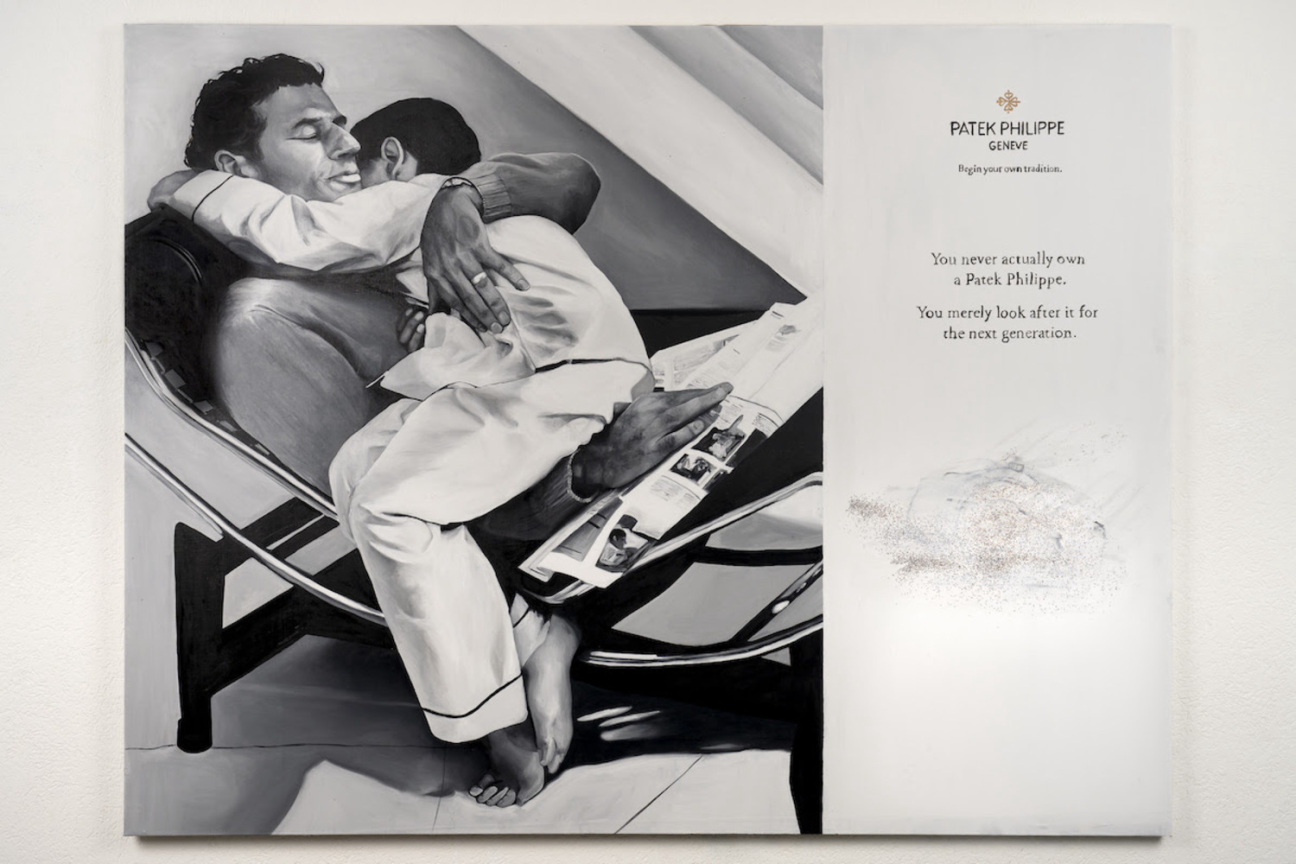

Across the East River at MoMA PS1, Jasmine Gregory’s solo show is a single-room installation incorporating paintings and video. Monochrome canvases embedded with glitter, a puzzle piece, and human hair mingle with figurative paintings, such as a serviceable copy of a Patek Philippe advertisement depicting a man and a boy in a boat. Nearby, a related work that reproduces another grisaille watch ad—what looks like another father-and-son scene, though in this one they sit on a Le Corbusier chaise longue—awaits visitors.

The intentionally messy monochromes next to the sleekly painted ads send up both heady abstraction and Richard Prince’s Pictures Generation ad play. (Swap the rugged masculinity of the Marlboro man for genteel European masculinity here.) A translucent rectangular platform at the center of the room acts as a sort of chandelier, with toppled martini and champagne glasses within. A video on the far wall, shot at an off-kilter angle, records a trip through the aisles of a German-language grocery store.

Gregory seems to be gently lampooning the art world’s proximity to luxury, creating an installation that feels like an aftermath, the instant when the lights come on at a bar. Here, that immortalized moment of truth reveals a Bergdorf Goodman ribbon resting on the floor a few feet away from a toppled Comme des Garçons perfume bottle.

Down the street at SculptureCenter, in the most affecting show of the bunch, the Madrid-born and Berlin-based artist Álvaro Urbano similarly mines art gold from ruin. Urbano’s project is built from the remnants of another’s: He salvaged parts of Atrium Furnishment, 1986, made for a Midtown skyscraper’s lobby by the American utilitarian modernist, Scott Burton—an artist who worked at the intersection of furniture and sculpture, and died of AIDS-related illness at the age of 50 in 1989. The semicircular seating of dark verde larissa marble, illuminated by a set of four pink onyx lamps, originally contained a water feature and plants. It was dismantled and removed in 2020.

In a poetic and elegiac reworking that transcends the source material, Urbano has mashed up the remnants of Burton’s vision with his own works—all in metal—recreating select flora inspired by the Ramble, in Central Park, a site for birding and cruising. You needn’t know any of this to grasp the sense of fecundity and autumnal over-ripeness that Urbano conjures within the space, scattering apples—often bitten—(that look real) and leaves (that look less so) throughout the space on the benches and floor.

It is remarkable that this ruin, discarded and stored away, was brought back into being—not to exist again as it was, but to be transformed through a loving and tender act of willful reincarnation.

Urbano’s intervention raises a question that many of these messy works also begin to approach: Why don’t we spend more time turning our collective trash, excess, errors, and ruin into beauty? At their best, these artists exalt the neglected or the everyday, bringing art vividly closer to life. And if we are willing to really look, with a steady gaze, this is where much of life is found—amongst the mess.

in your life?

in your life?