“Very demure, very mindful,” Jools Lebron said of her workday beauty routine in an Aug. 2 TikTok clip. For the popular trans influencer, it was a joke—an offhand jab at respectability politics dressed in diva steez. But a few days and several million views later, it mutated into something else entirely: a new normie lexicon of “I’m just a girl” memes, Rory Gilmore gifs, and mood boards of tasteful fits (usually modeled by women who look little like Lebron). Just when all the club classics and designer drugs had us thinking that Brat Summer would last forever, a modest new microtrend was here to take us back to school: Demure Fall.

Whether this is a frivolous fad or an expression of deeper cultural anxieties is hard to say. The speed with which the whole thing arrived suggests that it will fade before anyone can sort it out. But maybe not. In recent years, a growing number of painters have been unpacking the same themes of feminine etiquette and presentation at the heart of Demure Fall and the Venn-diagrammed microtrends before it, from Cottagecore’s playful reclaiming of farm fashion to the alt-right fundamentalism of Tradwives. But for these artists, something bigger is in the air.

Some blur the lines between critique and cosplay, reveling in regressive archetypes to make sense of their creeping hold on the cultural imagination. See the schoolgirls breaking bad in Karyn Lyons’s recent show at Anat Ebgi, or the “echoes of Balthus, Edward Hopper, or Norman Rockwell (by way of Lana Del Rey’s profane tmesis)” that one critic observed in the prurient portraits of Shannon Cartier Lucy. It’s why the paintings in Anna Weyant’s upcoming London show at Gagosian have a fairy tale feel. If the artist’s “subjects at first appear strangely calm,” as novelist Emma Cline once wrote of Weyant’s work, “On second glance their remove starts to look like a choice, an exhausted opting-out or a calculated pose, a weaponized strategy formed as an illogical response to a ridiculous world.”

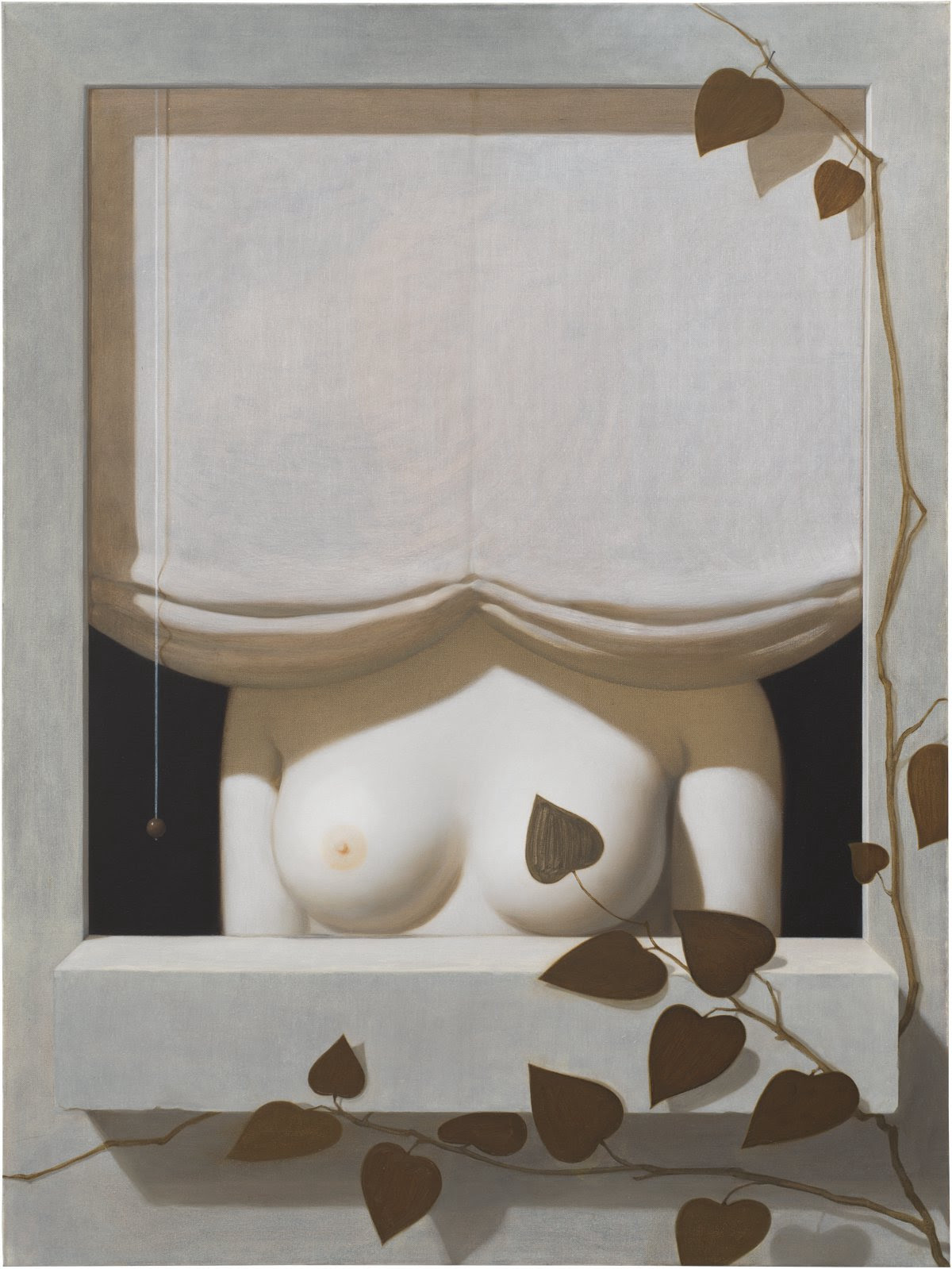

Others, like Sabrina Bockler, draw on the tropes of classical painting for insights into our contemporary mode. One work in “Coquette,” the 37-year-old artist’s recent show at New York's Hashimoto Gallery, depicts a delectable spread of aphrodisiacs; another centers on a bare-breasted woman in a Rococo-style dress preparing a mysterious concoction. Both were inspired by Bockler’s research into ancient love potions, used by women of history and myth to secure status through marriage or off their partners. In this lore, Bockler saw a metaphor for the damned-if-you-do, damned-if-you-don’t dilemma so often thrust upon women. “It’s a double-edged sword,” she says. “You’re either the villain in the story, or this innocent archetype of beauty.”

These projections “all pile on top of each other until the female body, like Atlas holding up the world, is left struggling under the weight of all that has been ascribed to it,” Jesse Mockrin, painter of Mannerist fantasies, wrote of the women figures in her 2023 exhibition at James Cohan. Mockrin’s heroines are split, doubled, and refracted by mirrors; they see themselves just as they see us looking at them. Are these women empowered by their awareness of the gaze or just further ensnared in its recursive trap? Their glassy-eyed expressions offer no answers.

A similar ambiguity colored the domestic tableaux of Marisa Adesman’s last show at Anat Ebgi. In these paintings, the rooms of the home become a stage for nightmarish theater, full of gendered innuendos and Freudian haunts. Dining room forks are bent in erotic poses or twisted into violent instruments. Kitchen candles light themselves. A woman is made of flesh one instant, turned into a translucent vessel the next. “Who is she?” the 29-year-old artist asks of this recurring figure, still unsure of the answer herself. “Is she in service of the household or is she working against it?”

The same question might be asked of those who have indulged in the demure of late. Can images of the feminine ideal really be used to dismantle the feminine ideal? Or, as one recent microtrend explainer put it: “Are we in on the joke, or the butt of it?” For Bockler, at least, the upshot is clear: “While these trends might appear to have fun with traditional [roles],” she says, “they often end up reinforcing outdated and regressive ideas.”

Still, others aren’t so eager to draw conclusions. “The way culture has taken these ideas and run with it—there has to be something there,” Adesman says, either hedging out of uncertainty or playing coy to preserve the mysteries of their work. Long before the painter learned of brat and demure, she obsessed over author Elizabeth Gilbert’s concept of “martyrs” and “tricksters”—the former a self-serious worker who believes in change through pain and duty, the latter an agent of chaos, prone to provocation in the name of boundless experimentation. “I like that push and pull,” she said, careful not to identify with either figure.

Instead, she pointed to a podcast where Jungian analysts break down our latest microtrend in the soporific tones of public radio. It was a great listen—and also kind of a demure thing to recommend.

in your life?

in your life?