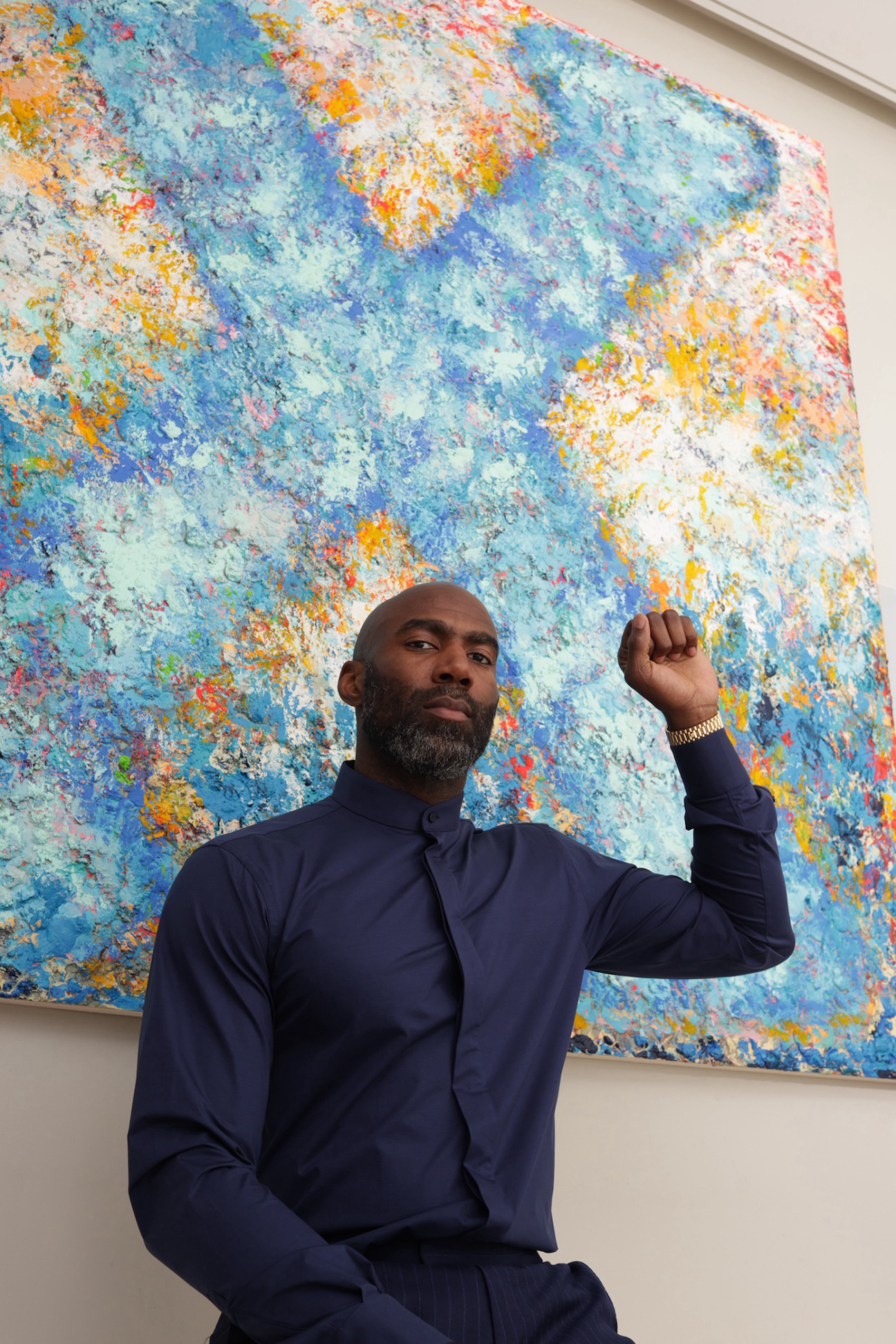

For many, the transition from an NFL career to the world of art collecting might seem like a leap. But for Malcolm Jenkins it was a natural evolution deeply rooted in the culture and creativity that shaped his upbringing. Growing up surrounded by paintings by his aunt, Cynthia Vaughn, Malcolm was introduced early on to the power of art in capturing the Black experience. However, it wasn’t until his retirement from football in 2022 that he immersed himself in the art world—driven by a desire to engage with the creative minds behind the works he loves.

Jenkins’s first studio visit was a turning point—one that broadened his understanding of the visual arts and propelled him into a journey of collecting with purpose. Now, with a trove of works that reflect the rich tapestry of the African diaspora, Jenkins is focused on bringing attention to underrepresented artists and supporting the growing intersection of athletics and art. Here, he shares insights on navigating the art world as a newcomer, the importance of representation, and why he believes there’s never been a better time to step into the world of collecting.

Take me through your transition into collecting art.

I grew up with my aunt Cynthia Vaughn’s art covering our family’s walls. It was work depicting scenes of Black life and imaginative, fictional topics. I wasn’t formally trained in the language of art, but as my career progressed and I gained more access, I realized I wanted to take collecting seriously. That’s when I started spending time with artists and really got into it.

One pivotal moment was when I got an invitation to visit Tavares Strachan’s studio. I was skeptical at first, but thankfully, I went. Meeting him and experiencing his work was a game-changer for me. His art explores everything I love—sharks, space travel, and hidden history. During our conversation, he told me, "If you want to be a collector, you should go to the Venice Biennale." I had no idea what that was, and he said, "It’s the Olympics of art, and it’s next week." I ended up going for just two days, and it was an absolute whirlwind.

How has your NFL career influenced your approach to art collecting?

It has certainly given me guidance on how to be new in a space. I remember what it felt like to be a rookie in an NFL locker room, and stepping into the art world felt similar. You’re at gallery openings and events with seasoned veterans, people who’ve studied art and are professionals, and you’re still trying to cut your teeth. But that experience was familiar to me and so I knew how to navigate it. For me, evaluating talent in sports is similar to evaluating art. Some things just stand out immediately, like watching LeBron James on tape where you just know it’s something extraordinary. Other times, it’s about consistency. You might not focus on a single piece, but you believe in the artist’s journey and want to be part of their growth, much like watching a player develop into something special.

As a new collector, who or what has been influential in your journey?

I've learned a lot from Anwarii Musa, my advisor, who has really guided me on this journey, introducing me to the key people in the art world. Early in my NFL career, one of my mentors was Keith Key. He was one of the few major Black collectors I knew at the time, and I remember walking into his office and seeing over 100 pieces of Black art. Before that, I didn’t even know Black people collected art, and he made me realize it was a possibility.

The artists I’ve met along the way have also been incredibly influential. The more I speak with them, visit their studios, and get to know them as peers, the more I learn. I gain new perspectives, understand their processes and stories better, and see what they’re trying to express. It’s an ever-growing experience.

After funding the Hank Willis Thomas sculpture at the Super Bowl, how do you see your role in supporting public art?

My focus right now is on the intersection between sports and art. More and more athletes are getting into collecting, which is exciting but also comes with some risks. We’re seeing books that address Black and other minority stories being banned in academic spaces, while at the same time, there’s been a surge in recognition for contemporary Black artists, particularly African and African American artists.

But there’s a disconnect: the collectors often don’t look like the artists themselves. This creates a situation where history is suppressed, and the art that tells these important stories is being consumed without the proper context or representation. I see this as a critical moment for people like myself to step in as a new collector, to highlight what’s happening, and to bring more attention to these artists. The Hank Willis Thomas project is a great example of that, aligning with my current focus both as a collector and in my career.

Your collection includes a lot of works from the African diaspora. How do you choose these pieces, and what’s your goal when collecting?

I really love this idea of just being. Many of the pieces I acquire reflect the diverse experiences of the diaspora–our struggles, joys, and everyday moments. I focus on contemporary artists but also deeply respect the titans who haven’t received their due recognition yet. I’ve collected works from Gordon Parks and Ernie Barnes, but I’m also exploring various mediums like abstraction, sculpture, portraiture, photography by artists like Alteronce Gumby to Dominic Chambers. It’s about surveying the landscape, finding artists I can connect with both personally and through their work, and building relationships that deepen my attachment to their art.

Tell me more about your connection with Ernie Barnes.

I love Barnes's work on so many levels. As a retired athlete, I find it inspiring that someone who also played in the NFL could redefine himself and become known more for his art than his sport. His paintings really resonate with me; they capture the essence of being Black, the joy, the emotion, almost like a freeze-frame of our experience. Growing up, I was surrounded by his images. My aunt, who was training to be an artist, would recreate his works, so I initially thought they were hers. As I got older and learned more about Ernie Barnes, his art became even more meaningful to me. His images have always been a part of my life and they always will be.

What excites you about digital art, and do you see it alongside your physical collection?

Before I got serious about collecting, I explored the crypto and NFT spaces. I was really intrigued by digital art, especially how artists can retain equity in their pieces. The economics of it appeal to me, having seen how tough it is for artists to make a living unless they’re at the top, similar to athletes. The ability to track both physical and digital works over time is powerful. I think it’s fair that artists like Kerry James Marshall could continue to benefit from their growth. I’m excited to see how digital and physical art merge in the future—I think there’s real utility there.

Any words of wisdom for new collectors?

Be patient. Figure out your own process, your rhythm, your reason, and know what your threshold is when it comes to investment. Just buy what you love. Like anything, when you love it, you’ll know it. The most rewarding part of this is supporting and getting to know the artists. When you hear their story, you can understand all the angles of an artwork and what goes into it and then you can go on and tell that story. Take advantage of that.

Did you face any challenges getting into the art world?

I entered the art world at an interesting time, focusing on the African diaspora. The landscape is changing and the faces of the collectors and the dynamics of the space are evolving. I haven’t experienced the isolation or friction that might have been felt five or 10 years ago. I want everyone to know that these spaces are more welcoming now. It’s the perfect time to step in and be part of the exciting and meaningful art being created.

Is there a piece you remember making a strong first impression?

I was at an auction with no plan on bidding on anything but I was compelled to raise my hand when I saw Gordon Parks’s Boy with June Bug. It’s a photo of a little boy with a junebug on his head tied to a string. I had been having numerous conversations around masculinity and what that looks like, coming to understand how, as children, boys are taught to swallow their feelings and frown on the softer moments they experience. Here was this image of a little boy, laying in the grass, the simple gesture of having a junebug on his head and I thought, Yes, this is what we want to encourage. Boy, that was beautiful. To be able to capture that side of boyhood in a photo and to show that not only is sensitivity okay, but it’s beautiful.

How do you curate artworks in your home?

I’m decorating my home now, and the best part is deciding what each room should express and how I want to feel in it. It’s about choosing art pieces that belong, how they interact, and creating a cohesive theme.

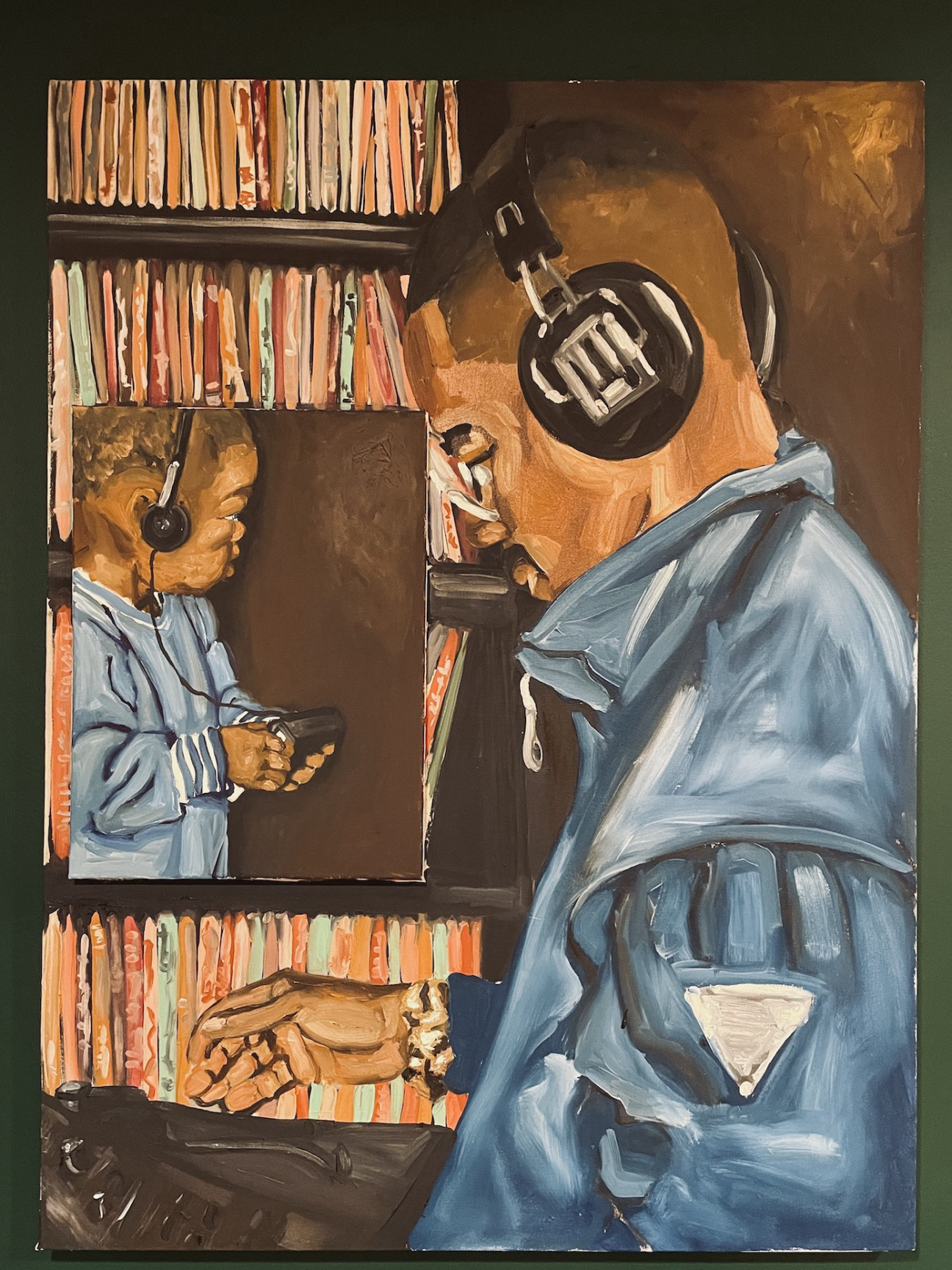

Is there a room you’ve perfected?

I just finished my basement, which I’m calling the Shadow Room. It’s a listening lounge with photos, paintings, and moody lighting. It’s a vibe—a mix of a game room and a place to chill.