In 2004, an erstwhile Southampton barbershop and beauty salon—opened in the 1940s by Emanuel Seymore, a Black barber with an entrepreneurial spirit who had migrated north from the Jim Crow South—was transformed, by village local Brenda Simmons, into the Southampton African American Museum.

Committed to preserving and promoting the area’s Black cultural history, SAAM is anchored by a permanent presentation on the building’s top floor dedicated to barber shops and beauty parlors—including Seymore’s own—as sites of community building, featuring ephemera from the barbershop and the neighborhood juke joint that was once next door. This summer, the museum’s rotating exhibition space hosts a solo exhibition from SAAM artist-in-residence Alvin Clayton.

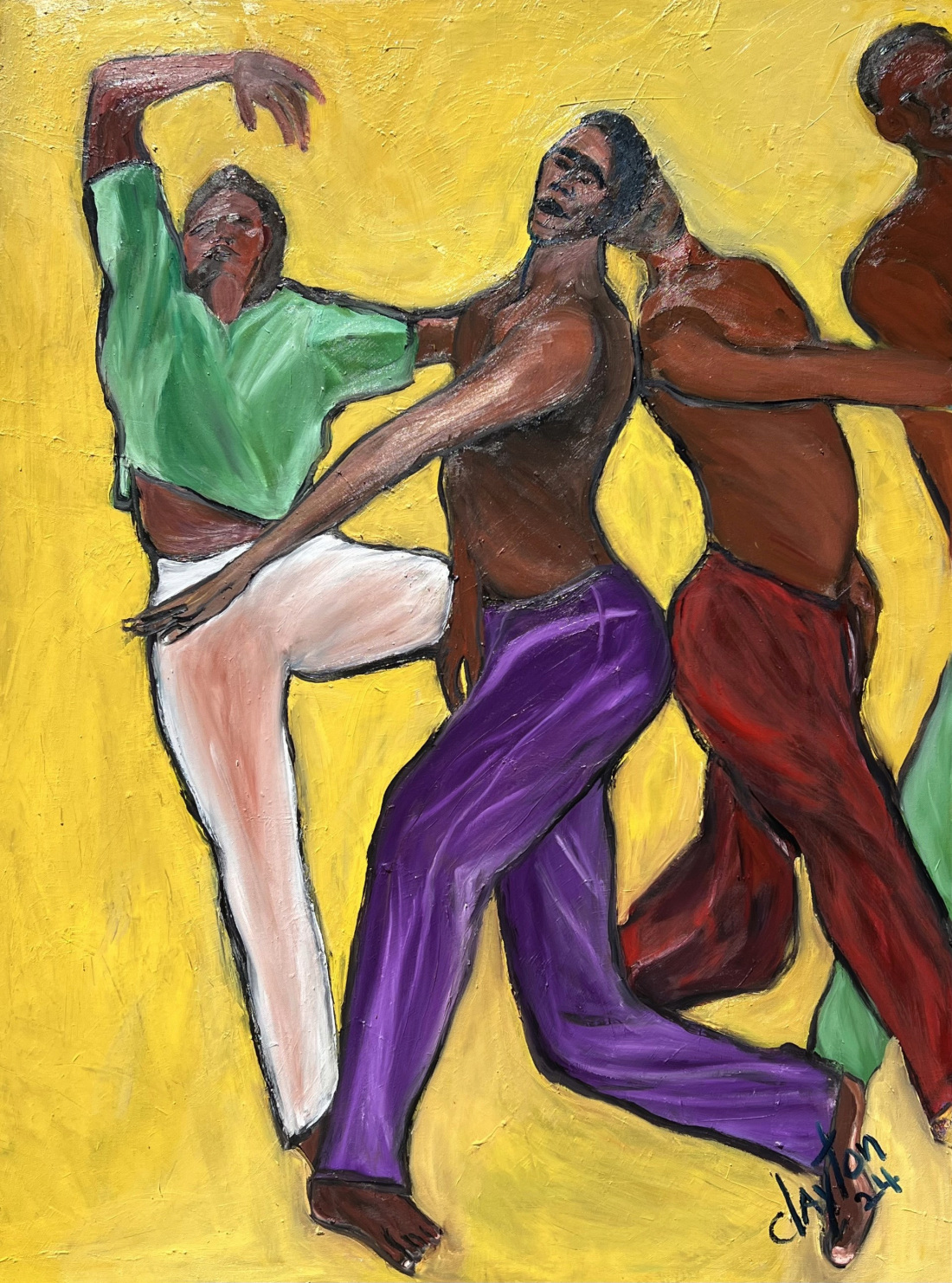

Clayton’s show, “Reflection of Time: Through the Eyes of a Caribbean-American Artist,” on view through Nov. 17, is in keeping with the museum’s site-specific exploration of place and belonging, and how the history of migration across the African diaspora—both forced and chosen—has resulted in a culture that is vibrant, far-reaching, and rooted in an ability to create and find community in any environment.

Born on the island of Trinidad, Clayton grew up drawing—“but in the era I was born in, you couldn’t tell your parents you wanted to be an artist,” he says. This passion for art was somewhat suppressed until Clayton, who eventually moved to New York and worked as a model for Wilhelmina and Ford Models in the 1980s and ’90s, was on a job in Paris and decided to visit the Musée d’Orsay—an outing that sparked a lifelong love affair with the paintings of Henri Matisse.

“The colors just spoke to me as a Caribbean person, and the patterns in his paintings were so reminiscent of growing up with my grandmother and the patterns of [her] tablecloth and the linoleum floors,” Clayton mused. The artist first taught himself how to paint by copying Matisse’s works. “There was a simplicity in his work that I felt that I could emulate,” he says, adding that his work as a model for photographers like Annie Leibovitz and Bruce Weber also impacted his understanding of portraiture. “I see how they look at subjects; the complexity of a painting comes from where shadow is cast, or what light you choose to put on someone’s face or in the background.”

“Reflection of Time” is the manifestation of Clayton’s goal to show work in museums this year. (In 1992, the Lee Arthur Gallery in SoHo first presented 27 of Clayton’s paintings, with 19 of them selling in the first two weeks, thus activating his career as an artist in earnest.)

The 25 oil paintings at SAAM, which Clayton says grapple with “the absurdity of racism,” mark a significant turning point in the artist’s work as more overtly socially conscious. “After the George Floyd murder trial [in 2021], my work changed. I started asking: What is the purpose of this painting? Who am I trying to reach and why?” The show also explores the artist’s distinct relationship to American history and culture as a Caribbean-born Black person. “The way that I look at things … is very much through a different lens,” Clayton says. “So [this show] is basically my journey that I’m trying to express.”

The Southampton African American Museum is ultimately a sanctuary for the multifaceted: From Seymore’s initial vision as owner and barber to Simmons’s stewardship as founder and activist, and now Clayton’s presence as artist and entrepreneur (his restaurant Alvin and Friends is located in New Rochelle), SAAM is a well of inspiring, subtle movement-making.

“SAAM is the first African-American site to be historically designated in the village of Southampton, and it’s the first Black barbershop to be transformed into a museum in the country,” Simmons says. Clayton, for his part, hopes this show honors the richness of Black history, but also the power of recognizing shared experiences across differences. “I really want to dig into our humanity,” he concludes, “At the end of the day we have more that joins us than that separates us.”

in your life?

in your life?