Women have always been at the center of Ghada Amer’s work. From her early forays into embroidery in the ’90s to her more recent engagement with bronze, the Franco-Egyptian artist has continued to subvert art historical and cultural expectations around the representation of female physicality and the interpretation of feminist texts and slogans.

Aspen was first introduced to the 61-year-old artist’s oeuvre in 2020, when Anderson Ranch Arts Center reinstalled her 2003 earthwork Love Grave on its front lawn. This summer, the mountain town will have a chance to dive deeper into the New York–based artist’s offerings with a show of recent work at Marianne Boesky Gallery’s seasonal pop-up. With the two series on view, “QR CODES REVISITED” and “Paravent Girls,” Amer continues her practice of manipulating symbols, materials, and traditions, inviting viewers to reconsider their understanding of women’s work and words.

Here, she sits down with CULTURED to trace the origin stories behind these series—and where she’ll go from here.

CULTURED: Tell me about the genesis of “QR CODES REVISITED,” which was the focus of your last solo show with Marianne Boesky and is also featured in the Aspen presentation.

Ghada Amer: I grew up with khayamiya, the textile tradition that inspired “QR CODES REVISITED.” It’s done in the street where my grandfather lives in Cairo. These people are called the tentmakers of Cairo: They used to make tents for events, like weddings, funerary receptions, and other ceremonies. Now, we imitate Western people, so we moved to hotels for weddings. But the tents were beautiful—they would decorate them, and then put them in the street. Then China came in, and instead of having these things sewn by hand, they became printed [because it’s much cheaper]. This was in the ’90s. The craft lost a lot of its men.

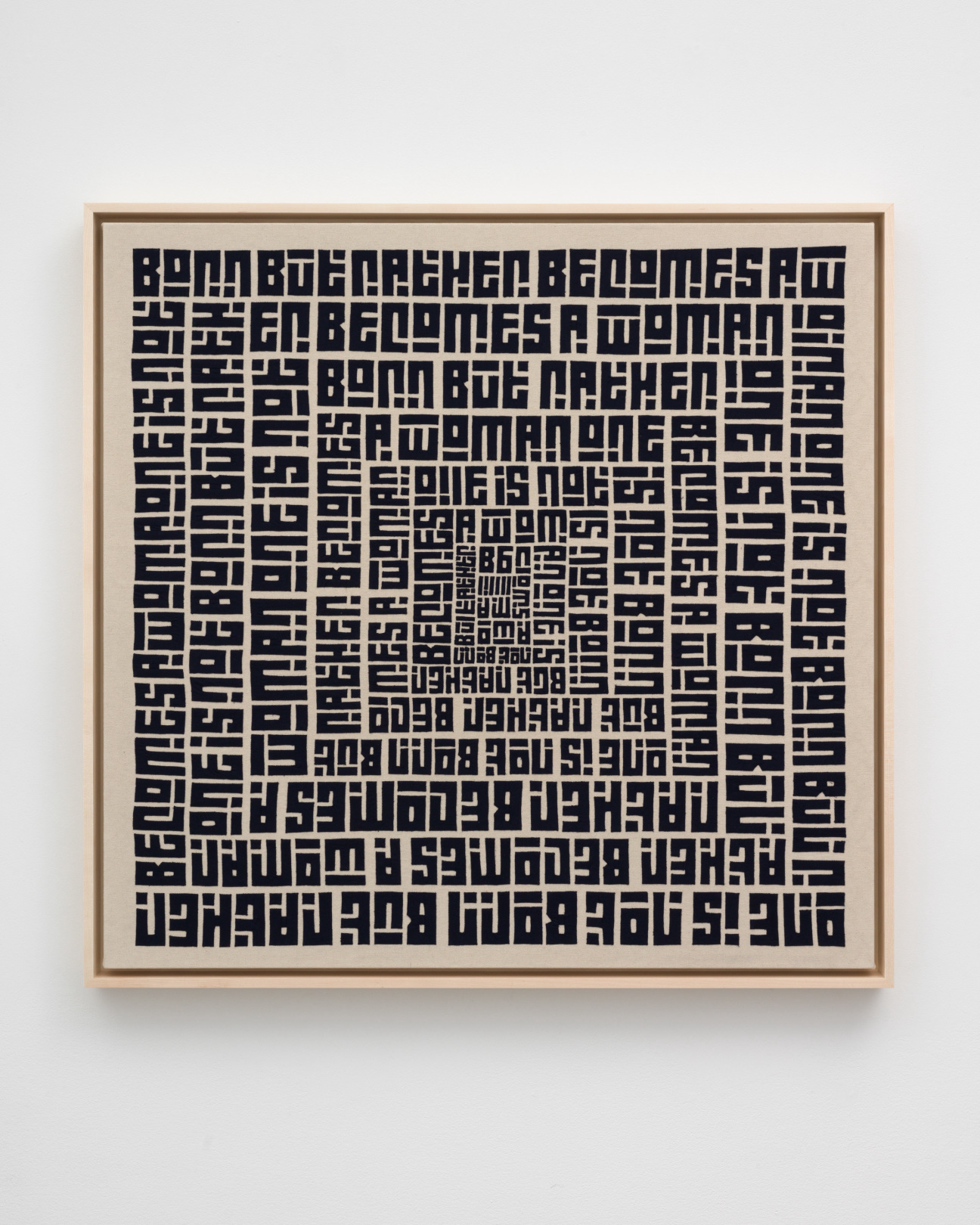

It’s very interesting, because it’s a craft that’s in the men's realm—like all the crafts that make money. For me, this project was like a little bit of vengeance … So it went from a booming craft to a dying one. Then there was a group of people who decided to save this craft. I was approached by one of them to work on a project. I met one of the craftsmen and chose something he had on the wall. I said, “Make me something like this, but instead of the Coranic script, I want you to write ‘A woman’s voice is revolution’ in Arabic,” and I left. I came back later, and my piece was ready. It struck me as very beautiful and interesting. I was like, What does this remind me of? Suddenly after six months, I realized, This is like QR codes. I hate QR codes, because they mean nothing. So, I got the idea to make QR code where I would embed feminist quotes. And I decided to make them in English, too, so more people could understand them

CULTURED: That’s a fascinating origin story. You would think that it came together very naturally.

Amer: Yeah, but nothing comes together in art that way. You don’t see it, and then the idea just comes from the sky to your brain.

CULTURED: “Paravent Girls” began with cardboard boxes that you found on the street. Why cardboard?

Amer: Each time I receive a book, it's like, Poor books, poor trees. The quantity of cardboard, especially with Amazon… it’s like cardboard is a trademark of America. You see it every day. Anyway, this is not why I chose cardboard. I started ceramics to produce a prototype for my bronze. I fell in love with ceramic and liked the idea that I could paint on it. During a residency, I needed to make a maquette, so I did it from cardboard. I made these beautiful drawings, all on cardboard. They were meant to be thrown out, but I said, “No, they are nice. I like them.” So I kept them. Then Tina Kim [Amer’s other gallerist] came to visit my studio before everything shut down with Covid. She found the drawings, and was like, “What are these, Ghada? These are beautiful.” Then she told me, “I’m taking them to Korea, I’m going to have them made in bronze.” So that’s how they [became what they are today].

CULTURED: What did you surround yourself with while making these two bodies of work?

Amer: My practice is fueled by current affairs. For example, the status of women. For me, it’s a current affair. I want to know what's happening in the world, especially in the Middle East.

CULTURED: You’re interested in current affairs, but many of the words used in “QR CODES REVISITED” are from the past.

Amer: I want people to remember that there's nothing to invent. Everything has been invented—we just forget. History is very short because it repeats itself. If we don’t remember, and if we don’t take good care of what we have learned in the past, we will go back to fascism. For me, it’s important to remember that everything is a quotation. Every thought, every thing, has been said.

CULTURED: Over the years, your practice has placed passion, feminist rage, and the power of the erotic at the center of the conversation. What is the place or the importance of the erotic in the art world today?

Amer: I don’t care about what the place of it is. It’s the place for me. This is what made me become an artist. This is what I want to talk about. We don’t know who decides what is or isn’t art. It’s not us who are going to decide—it is going to be years, 200 or 5,000 years. For me, right now, what is important is: I went into art because I had depression, and it’s art that pulled me out because I could have a voice. When I started in 1991 in France, it was not “important.” I don’t think importance is a good judge.

"Ghada Amer: New Works" is on view at Marianne Boesky Gallery in Aspen through July 24, 2024.

in your life?

in your life?