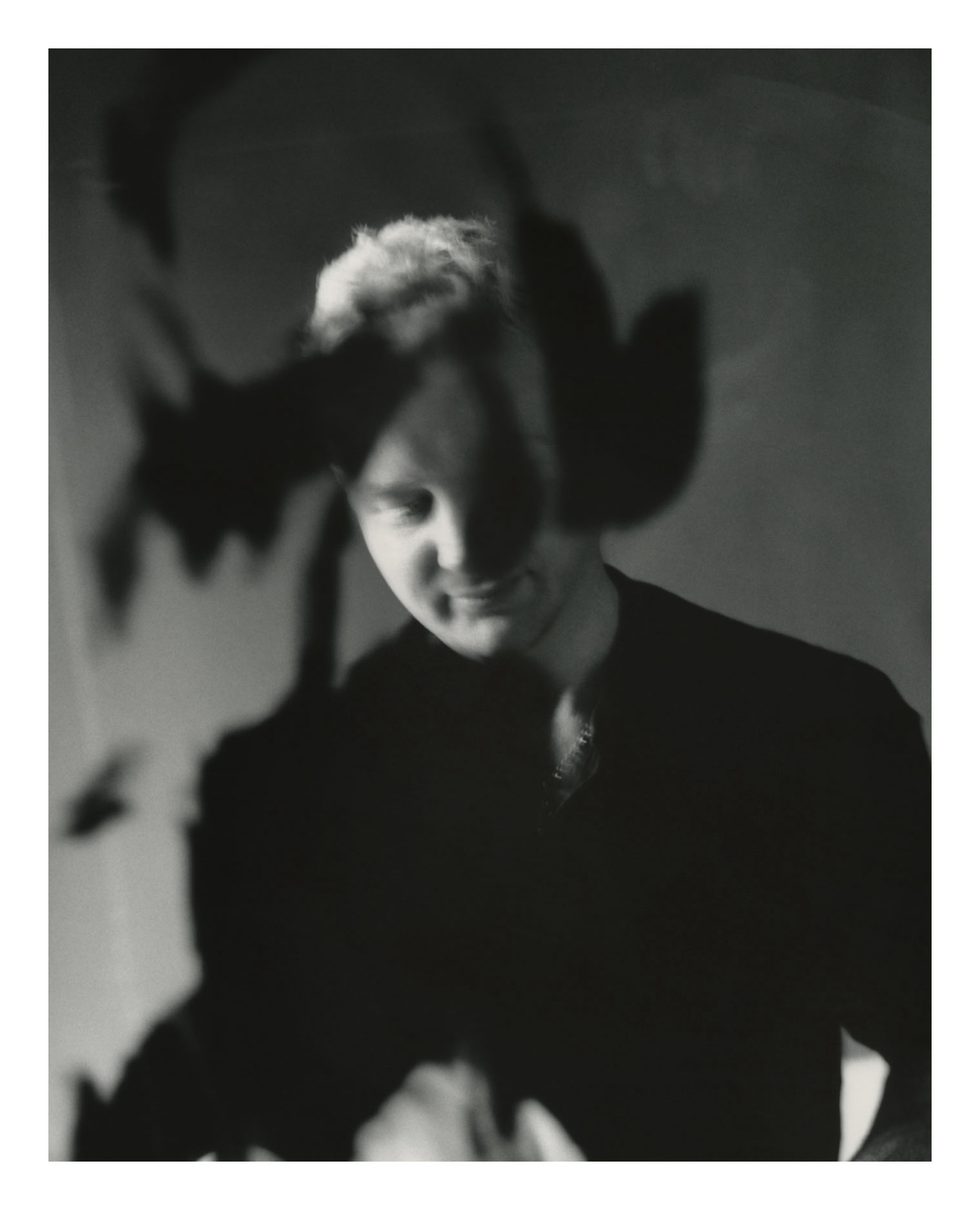

When we meet, Steve O Smith is facing one of the biggest moments of his career. He’s zipping around his East London living room turned studio, chipping away at a dauntingly long to-do list. In a few days, his designs would make their Met Gala debut, appearing on actor Eddie Redmayne and his wife, Hannah Bagshawe.

The space is suitably chaotic—a whirlwind of pins, paper, discarded fabrics, and tobacco dust. Lining the walls are images from his Fall/Winter 2024 lookbook, alongside his frenzied original sketches. “I do good work when I’m pissed off,” Smith lets out, gesturing toward his drawings. “I like to get into this state where it’s free-flowing, and I’m listening to music quite loudly and moving around. I’m always standing up—I never sit down to draw.”

It has been a transformative few years for Smith. After graduating from Central Saint Martins in 2022, the British designer, 32, has experienced a string of back-to-back pinch-me moments: His MA collection was swiftly spotted by stylist Harry Lambert, who called in his black-and-white figure suit for Harry Styles’s “Daylight” video. “It was quite shocking,” Smith remembers. (The same suit later made the fashion editorial rounds, appearing on the likes of Cate Blanchett.)

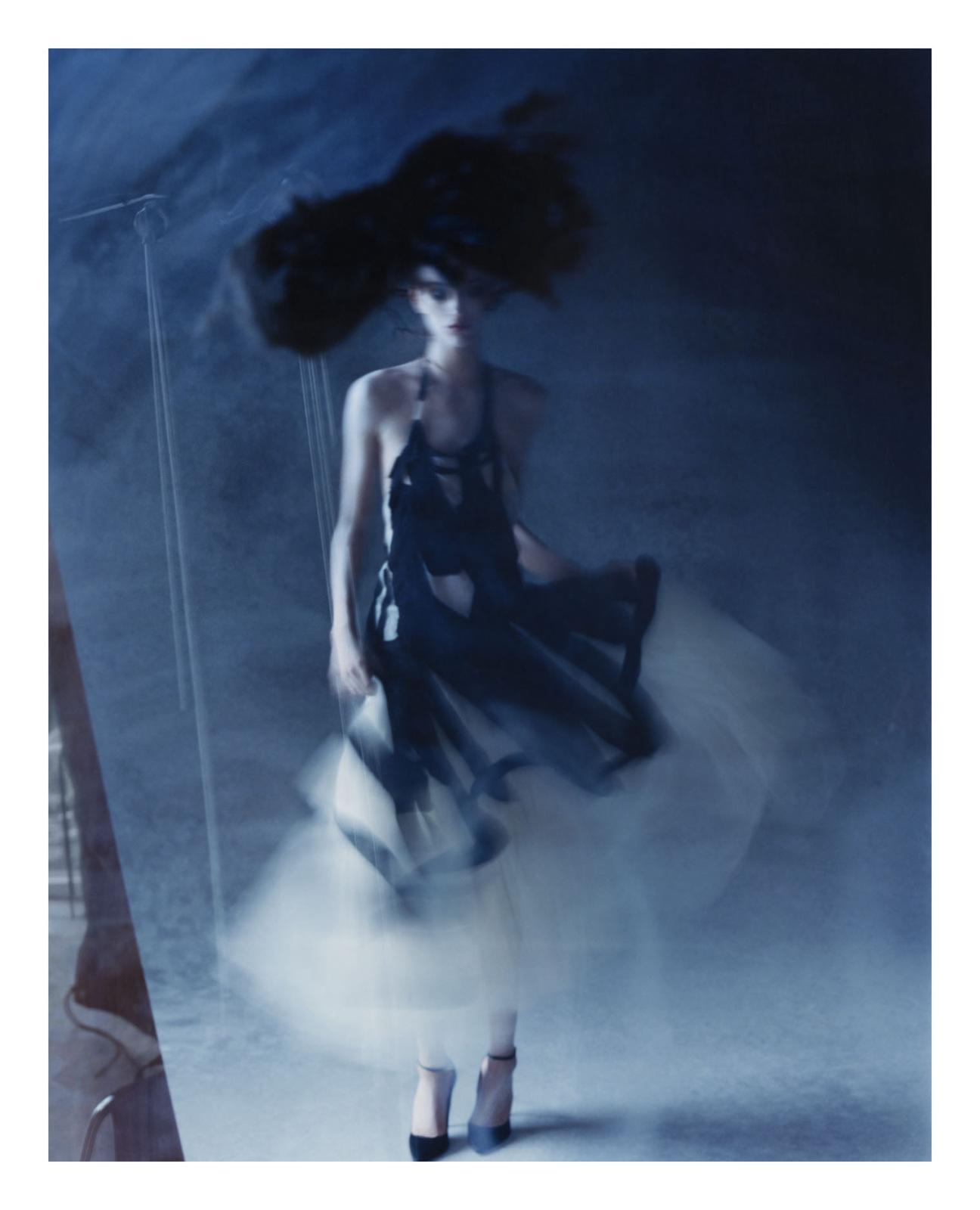

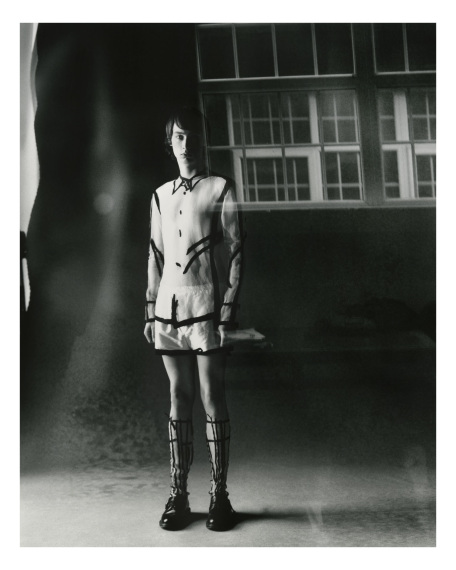

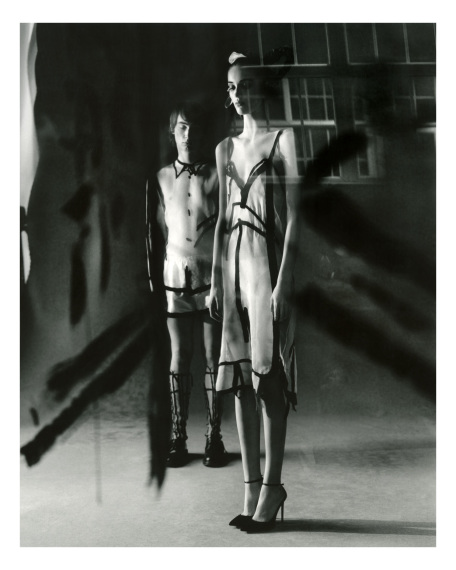

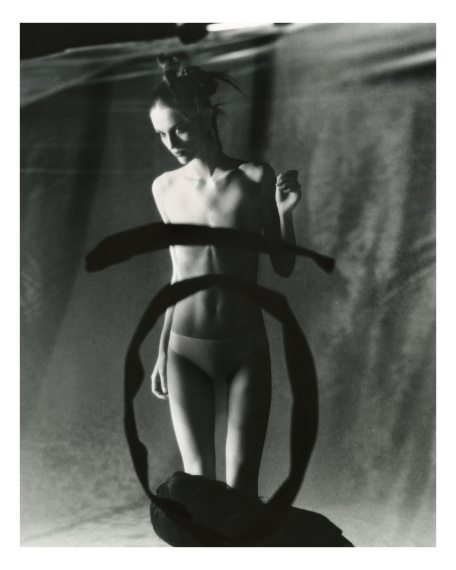

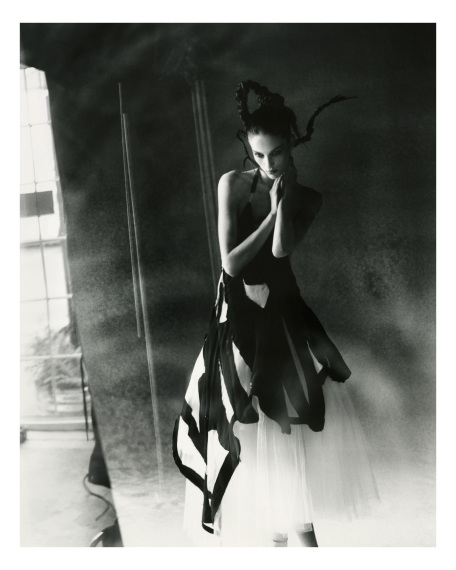

But the designer’s most recent Fall/Winter 2024 collection—which was also his official debut—sees his work reach new heights of refinement. Crafted from black silk and organza, Smith’s pieces feel more like enchanted life drawings, scribbles lurching off the pages of his sketchbook and scrawling themselves onto the body. It tracks that his main inspirations for the collection were 20th-century caricatures and German Expressionism—namely George Grosz and his “sinister” drawings of the Weimar Republic.

“There’s something funny, a bit fucked-up about them,” he says, eagerly grabbing a book of the artist’s early sketches. He flicks through the pages, pausing to study a drawing of three angry soldiers. “There’s something borderline ludicrous about the entire concept, which is what keeps me entertained … It feels worryingly current.”

Smith was born in Amsterdam but brought up in the U.K. He studied fashion at the Rhode Island School of Design, where he learned basic craftsmanship, including how to fit, sew, and pattern cut. It was a sturdy yet traditional foundation, but when Smith returned to London to start his own line in 2017, it didn’t take long for him to hit a wall. “I’d been doing wholesale, but I wanted to go back to school because I felt like there was more potential,” he recalls. “And then the pandemic happened.”

Burnt out from the “stressful and time-consuming” nature of wholesale, he began a master’s degree at Central Saint Martins—followed by a 10-week stint at the Royal Drawing School, where he rediscovered his childhood passion. “The tutors were like, ‘You’re doing something really interesting here, and you should try and translate that into what you’re making,’” he says, before laughing.“And so I did, with a lot of failures at first.”

Smith soon learned to surrender to his instincts. He flicks at a pile of papers on his worktable—hundreds of pages of drawings—and admits that he typically spends up to 12 hours a day doing rapid sketches, growing increasingly agitated in the process. “At a certain point, there’ll be an emotion in it,” he says. “The last few drawings I did, I was pressing so hard with the graphite stick that you could smell it. I was really attacking the page.”

He then applies this same process to his fabric-cutting, treating the material as an extension of the graphite. “I just start laying the fabric at the same speed that I was laying the marks down on paper, and then stitching them down.” The resulting designs, like his drawings, are pure id, alive with emotion and thrumming with energy.

The goal for the future, though, is to slow down. Smith admits that his natural state is to “move quickly forward,” but his main priority now is to give himself the space and time to nurture these more primal creative instincts. “I’m just able to draw and make the things I want to make, and I’m happy,” he says. “That’s partly from failing the first time around—I realized the things that I thought I wanted were not what I wanted at all.” His process may be slower and more intricate, but he sees it as a small price to pay. “For some people, creative freedom can be scary. But for me, it’s a weapon … I can do whatever I want, which is amazing and liberating."

It leaves Smith with a blank canvas of possibility, an intimidating prospect for any designer. But for him, it’s a chance to dig deeper. With the chaos of the Met Gala under his belt, he’s planning a return to his sketchbooks and a “refinement” of the technique he’s already mastered, particularly around form and gesture.

That doesn’t mean he won’t be trying something new, though. The designer’s next collection, he notes elusively, will experiment with “tone”—a new territory—and a focus on color is on the horizon as well. But he doesn’t want to get ahead of himself. “Right now, I’m actually forcing myself to try and stay still, right where I’m at.”

in your life?

in your life?