Artist Adrian Nivola awoke in London in late May in the special kind of haze one feels when caring for a 3-month-old baby, but his easy demeanor is still felt, even through Zoom. He speaks with openness about his family, fluidly recalling stories of his grandparents and the home that has been in his family since 1945. He tells me how it all started in Springs—the spirit of this entire place we all lovingly refer to as “out East.”

There, his late grandfather, sculptor Costantino “Tino” Nivola, worked with sand in a style that was nearly undefinable. Yet the way of life that he designed for himself became the blueprint for Hamptons culture as we know it. There was a fluidity between nature and the home and a culture of creation in this place. Springs was home to some of the country's most prominent Abstract Expressionists, from Jackson Pollock to Willem de Kooning, and they gathered at the Nivolas’s to experience a landscape built with memories from another world—Sardinia.

Nivola first immigrated from Italy in 1939 with his German-Jewish wife, Ruth Guggenheim. They landed in New York—living downtown, working in factories, and eventually finding stability when Tino took a job as an art director for Interiors magazine. The city brought them some connections, yet they craved contact with the land. By 1948, they bought a house in Springs, just down the road from Jackson Pollock and his wife Lee Krasner, another artist couple who came to define American Abstract Expressionism.

“My grandfather was an amazing cook,” Nivola tells me. “He and my grandmother loved to host people in their home, and it became a social hub in the Hamptons in the 1950s and 1960s. They invited critics, artists, and all of their community to enjoy this property that he built with his own hands in the Sardinian style.”

It turns out the food was essential, because of the famous '50s cocktail hour. Costantino found it boring when everyone drank too much and conversation would go off the rails. He discovered a solution that set the tone for the bacchanalian feasts that kept them at the heart of the culture.

“He went to an Italian butcher in the West Village and brought all these prosciutto legs back to Springs, where he hung them in the garden from the trees so people could eat, and it would slow down the process of them being inebriated. It would preserve the conversation,” Nivola recalls, before describing the property's unique aura: “He designed the whole compound, piecemeal, with some elements coming directly from Sardinia and combined it with that modernist feel of the time. When I went to Sardina for the first time as a child, I immediately felt familiar with it.”

Over time, Tino turned his property into a living studio for him and Ruth, complete with tons of sand from the beach in the backyard. The playful spirit of the sculptures he made there, with his children Claire and Pietro, became part of a body of work. Every surface was a canvas for Tino—the ground, the exterior walls, and later, the sand.

In a 2021 show held at Magazzino Italian Art in his honor, then-director Vittorio Calabrese said his work was nearly lost to history because it could not be categorized. It was experimental, often large-scale, and made from found materials. He captured the ephemeral nature of sand by pouring plaster into his geometric carvings. His commission for Olivetti on Fifth Avenue was what made his name.

The store, which sold typewriters, was akin to an Apple store at the time, showcasing a technological future rooted in experiential design. Nivola's work also seemed to resonate with architects, who commissioned façades for civic and private buildings, including the headquarters of local newsrooms in Bridgeport, Connecticut, and beyond. Despite his close friendships with creative giants like Pollock and Le Corbusier, Tino never wavered from his own style.

“The artists used to give each other works in progress and lend them to each other to live in their contexts,” says Nivola. “Pollock lent my grandfather a painting. It sat in the living room in the house, and after a while, my grandfather told Pollock he couldn’t live with it. It made him nervous, and the children would fight when they were near it. He gave the painting back to Pollock. They were brutally honest with each other in these exchanges, but this didn’t rupture their friendship: Pollock gave my dad his first bicycle.”

Tino also recounted to Nivola how Piet Mondrian later visited Pollock’s studio, where that painting, titled Stenographic Figure, hung. He loved it and wrote a letter to Peggy Guggenheim saying that Pollock was the most significant American artist of the time. That very painting launched his career and now hangs in the Museum of Modern Art. Nivola recalls a picture of his grandfather looking at it with his head cocked to the side.

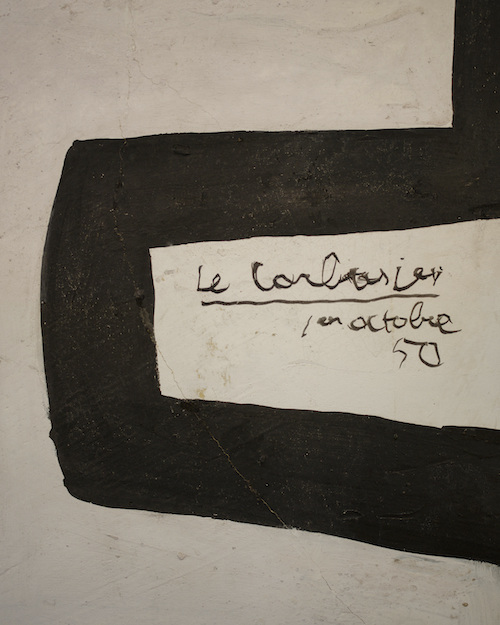

For Le Corbusier, it was different. There was a natural alignment between the two artists, who were both skeptical of the American experimentation of the time. Le Corbusier even experimented with sand castings when he stayed in Springs. Le Corbusier’s commitment to honing a painting as though it were a perfect machine was a notion he feared would be lost from the new developments of painting, and he distilled this philosophy with Tino.

Le Corbusier would travel back and forth from France to New York, usually while working on a project for the United Nations. Arriving from his travels, he brought suitcases of sketches and paintings he had been developing for years. Nivola’s grandfather remarked that Le Corbusier often brought more sketches than clothes.

He had been searching for the right context to develop a large-scale mural and was drawn to Nivola’s renovation of the formerly dilapidated farmhouse. The concept for the resulting mural had been previously sketched and refined by Corbusier for some time. The mural was painted over a two-day period in the Nivola house, after Tino ran out to get paints for Le Corbusier. There it stayed, in the same spot where the Pollock once sat in the home.

This home is a quiet center-point for the creative life in the Hamptons, born out of Tino’s connection to the land, which helped him find his voice as a multifaceted artist. In turn, he created a destination for a community of artists who, like him, found inspiration in the isolation and connectivity to nature, as well as the space to express themselves in new and innovative ways. This original band of artists created these pillars of life from Springs. Today, we all walk in their footsteps.

Order your copy of the Hamptons Edition here!

in your life?

in your life?