With the 1986 film Pretty In Pink, Andrew McCarthy became what the press might designate a ‘heartthrob.’

He played Blaine, a sensitive “rich-y” whose timid heart softens at the sight of Andie (played by Molly Ringwald), an arty cool girl who lives on the (literal) wrong side of the tracks with her father (Harry Dean Stanton). Instead of falling into the arms of her devout sidekick Duckie (played by Jon Cryer), Andie ends up with Blaine, perpetuating a mythical trope that posh boys like Blaine might have a kink for have-not, not-blonde Gen X girls. We all had a crush on him.

During the latter part of that decade, McCarthy, Ringwald, and Cryer, along with his St. Elmo’s Fire co-stars Demi Moore, Judd Nelson, Ally Sheedy, and Rob Lowe, were omnipresent; you couldn’t go to the movies, turn on your TV, or hit a magazine stand without being greeted by at least one of them.

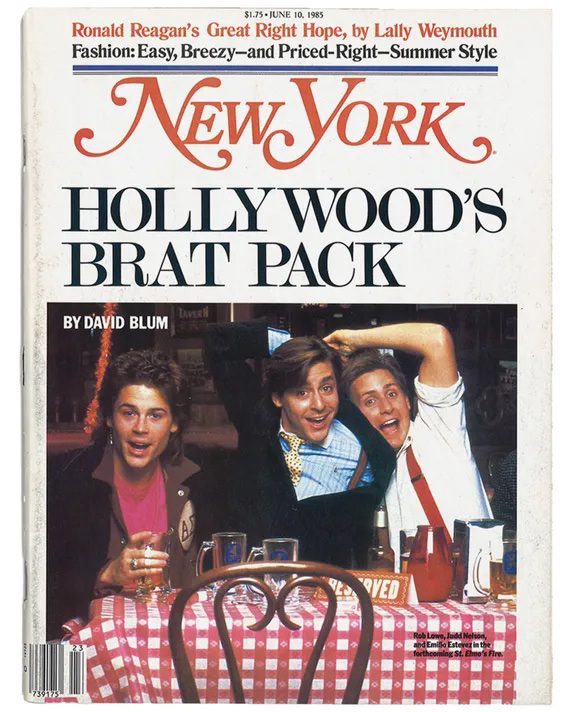

It wasn’t long before a few members of the unofficial posse met up with journalist David Blum while carousing at the Hard Rock Cafe, which led to Blum coining the “Brat Pack” in a 1985 New York magazine cover story. He compared their hard-partying, skirt-chasing ways to Hollywood “Rat Packers” of yore like Frank Sinatra, Sammy Davis, Jr., and Dean Martin, but “brat” was one role McCarthy didn’t care to play.

In his new documentary Brats, which makes its premiere at Tribeca Film Festival this weekend, McCarthy revisits a cross-section of his Brat Packer brethren, among them Ally Sheedy, Demi Moore, Emilio Estevez, Rob Lowe, as well as actors Lea Thompson and Tim Hutton (from the “Pack” periphery), to see how the label has affected the trajectory of their careers.

The result feels closer to being a fly on the wall at a college reunion than watching a full-fledged documentary. “The second we saw each other it was like, ‘Oh my God! It’s you!’” McCarthy tells me over the phone. “When I see Rob Lowe walk in the room, I see myself at 19 years old, the way people see me. He's sort of the avatar of my youth, the way I—or the ‘Brat Pack’—might be the avatars of your youth.”

The documentary expands on McCarthy’s memoir Brat, including the experiences of the “brat pack” label of his peers while unpacking his own years in the ranks. “All we ever want in life is to be seen,” he says. “It was such a good label and it stuck, and that was that. I felt like I lost control of the narrative of my career overnight.” It’s palpable how McCarthy at once delights in performing but detests subjecting himself to public scrutiny. “I want to be successful, and on the other hand, I just want to get the fuck out of here,” he admits. “I'm like a Doctor Dolittle animal, that push-me-pull-you with a head on both sides, sort of pulling itself back and forth. It's not a great way to make progress, but eventually, you just sort of come to terms with the way you are.”

This is likely why McCarthy has designed a career more conducive to his IRL personality, adding acclaimed travel writer, author, and TV director to his resume. “I'm more suited to sitting alone in a room and writing than being on a red carpet,” he laughs. He admits writing and directing also empower him to drive narratives instead of being driven by them. “To misquote that Joan Didion line, ‘I write to figure out what I'm thinking’—I write to figure out what I'm feeling. These are my words: If you like it, great. You don't like it, it's my fault.”

At the end of the doc, McCarthy inevitably faces Blum and comes to terms with the fact that the journalist, like him, was just young and doing his job. “I hated it at the beginning, and now I've come to realize it's one of my greatest professional blessings,” McCarthy sighs. “But fame just never had any real intrinsic value.”

The actor does admit to a few of fame's perks, like the meta ‘80s moment when he was invited to Sammy Davis Jr.’s place for drinks—a Brat Packer clinking glasses with a Rat Packer. “Liza Minelli drove me home in a Rolls Royce at the end of the night,” he marvels. “She was more sober than I was!”

in your life?

in your life?