Newsstands across Cannes are packed to the brim this week with stories about female industry leaders and a slew of #MeToo-inspired projects. But beyond the media buzz and the return of the event's sexual harrassment hotline, the 2024 Cannes Film Festival isn’t doing much to address gender inequality.

Out of 22 films in its main competition, only four are by female directors; in Un Certain Regard’s highlight of young talents, that figure is six out of 18. This makes the festival’s symbolic gestures ring hollow, at risk of petering out without any meaningful structural change.

One promising sign is Cannes promoting exciting female debuts and early films. Agathe Riedinger’s Wild Diamond, about a marginalized young Marseillaise (brilliantly played by newcomer Malou Khebizi) dreaming of starring in a reality show, is brutally frank about the entertainment industry’s sexualization of female bodies. The girl-farmer at the heart of Louise Courvoisier’s Holy Cow likewise fights chauvinism. Even in Laetitia Dosch’s lighter Dog on Trial, based on a real-life canine trial, gender becomes a hot topic when some breeds are shown to be misogynist.

Coralie Fargeat’s The Substance is a real standout, similar in tone to Julia Ducournau’s Titane, which won the Palme d’Or in 2021. It stars Demi Moore as an aging reality TV star who, after injecting herself with a gene-altering substance, births a younger replica (Margaret Qualley). Fargeat and Moore capture the bodily and mental annihilation of a woman who incarnates society’s pathologically rigid standards of beauty. A cinematic feast ending in an orgy of gore and guts, The Substance confirms the renaissance of women-directed genre films.

Another visible change in Cannes is its giving a platform to the #MeToo movement. French actress Judith Godrèche, who came forward against Harvey Weinstein and accused French directors Jacques Doillon and Benoît Jacquot of assault and rape while she was a minor, appeared on the red carpet the day her short, Me Too, showed here. “Our industry has rules, but doesn’t follow them,” Godrèche said at a special event.

#MeToo became the festival’s crie de coeur since the opening night, which featured Quentin Dupieux’s sardonic comedy, The Second Act. In the film, a male actor shooting a movie frets endlessly about being canceled, while his colleague makes unwanted advances on a female lead, played by Léa Seydoux. In a press conference, Seydoux said that the movement has made her feel safer.

Violence against women has been the theme of many films in Cannes, such as Hala Elkoussy’s The East of Noon, whose protagonist is raped by a sheriff; Rungano Nyoni’s On Becoming a Guinea Fowl, the first Zambian film to be presented at Cannes, in which a man’s sudden death stirs hushed memories of his sexual abuse; Yolande Zauberman’s The Belle From Gaza, documenting aggression against trans women in Tel Aviv; Sandhya Suri’s stirring crime drama Santosh, in which a policewoman investigates the rape and murder of a low-caste girl in Northern India; and Being Maria, based on the memoir of Maria Schrader, who was instructed by Bernardo Bertolucci to perform an unsimulated rape scene in The Last Tango in Paris.

#MeToo is also at the center of the satirical horror The Balconettes by actress-director Noémie Merlant and co-written with director Céline Sciamma. Their earlier collaboration, the critically acclaimed feminist queer film The Portrait of a Lady on Fire, premiered at Cannes in 2019. It starred Adèle Haenel, who sued director Christophe Ruggia for sexual assault and quit cinema to protest the industry’s prevailing complicity.

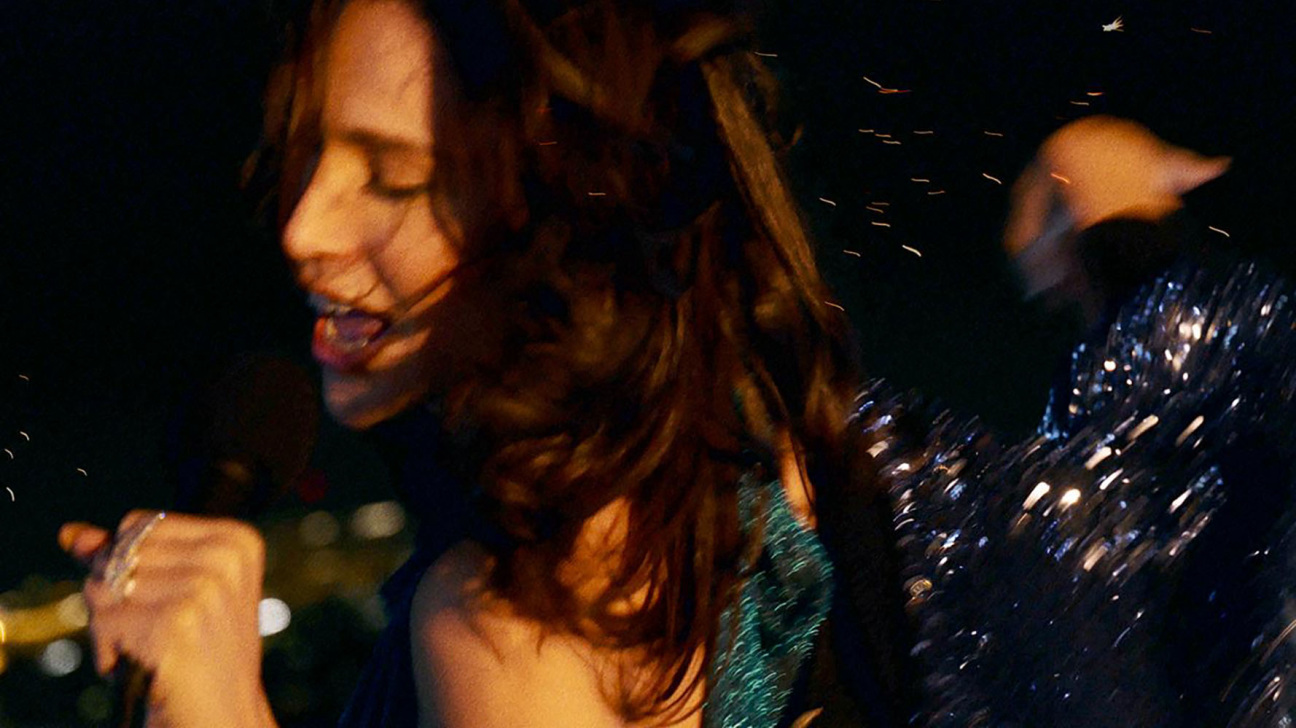

The Balconettes, in which Merlant plays one of the three female friends taking a gory revenge on a rapist, is a searing homage to the courage of Haenel and countless other women who have since come forward. Unlike Fargeat’s relentless horror, Merlant’s film ends with crowds of women marching in the streets to celebrate their freedom from brutality. While this still feels like a fantasy, there are signs that the industry may slowly moving in the right direction—but not without an assertive push from women in cinema.

in your life?

in your life?