“You don’t save your soul [by] just painting everything white,” Ettore Sottsass once wrote. One look at the late Italian architect’s polychrome designs makes it clear he was destined for salvation.

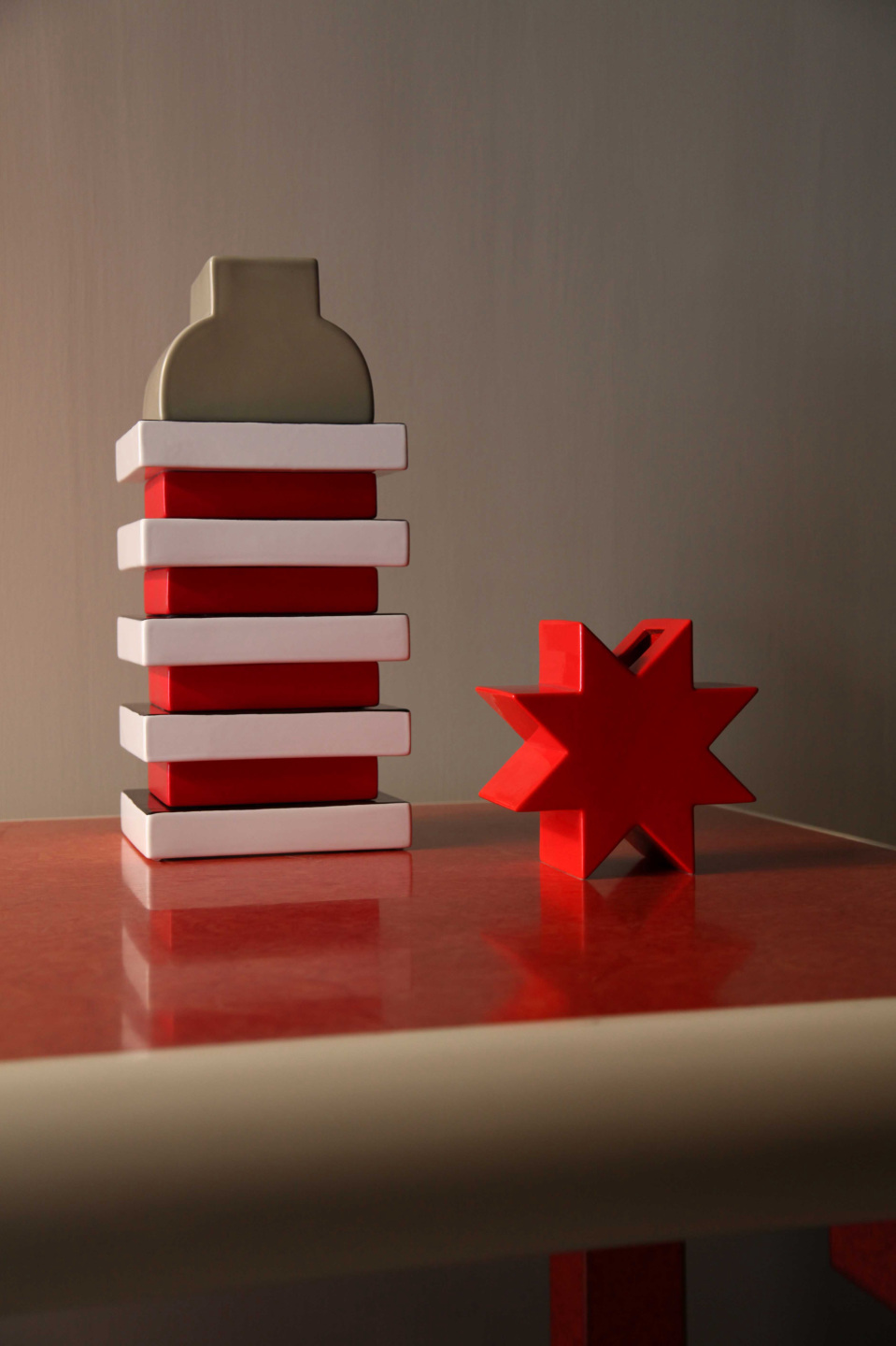

Sottsass, who died in 2007 at the age of 90, lived his life in color. After being held as a prisoner of war in Germany during WWII, he moved to Milan to open his own design firm, and later co-founded the wildly influential Memphis Group. Sottsass incorporated bright palettes and bold shapes into his whimsical designs, an insistent optimism postwar consumers desperately welcomed.

Tomorrow, Raisonné will open “Ettore Sottsass: Shapes, Colors, and Symbols,” an exhibition dedicated to the architect’s enduring work. Seventy-five works across five decades of the designer’s career have been curated for the show, bringing ceramic, glass, and industrial creations, as well as unique commissions, to the gallery’s SoHo space.

In an era where tides have turned to the starker tones of quiet luxury, Sottsass’s oeuvre feels more vital than ever. The Ultrafragola mirror he designed for Poltronova in 1970—which conquered Instagram well over four decades later—has been replicated and coveted to no end, its blush, undulating frame both grounding and trippy. The Olivetti typewriter he designed in 1969 (cherry red for Valentine’s Day) turned a then commonplace household object into an unlikely source of joy. His goal wasn’t reinvention, but rejuvenation—for Sottsass, good design functioned like “an aspirin for a headache."

Raisonné Founder Debbie August and Director Jeffrey Graetsch made sure to highlight the broad scope of Sottsass’s work in this exhibition, which opens in May and is timed perfectly with the designer’s posthumous renaissance. “We hope to show the breadth and brillance of his creative talent,” says August, “not only as a trained architect, but also a designer of ceramics, glass, furniture, and industrial objects.”

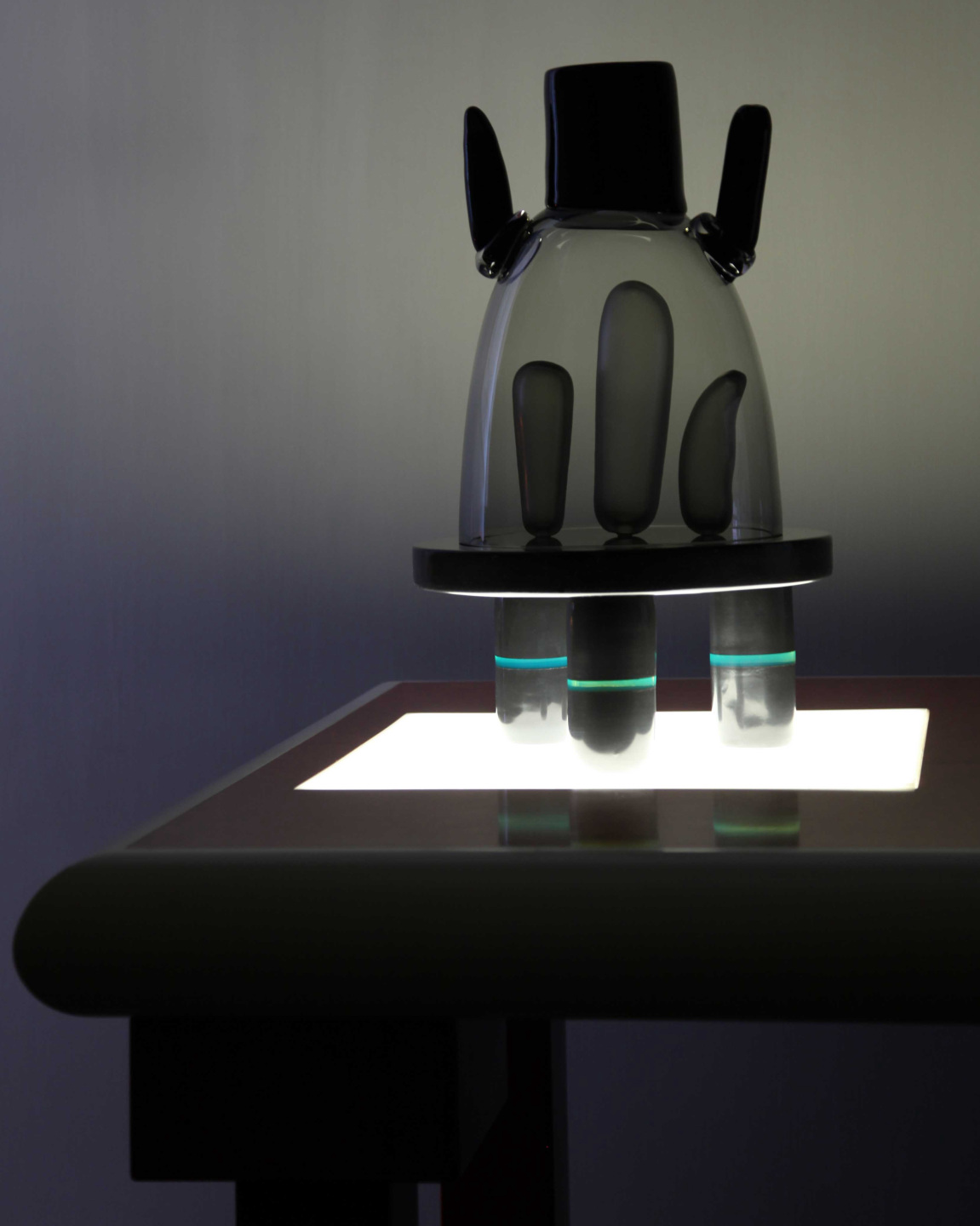

Indeed, rare blown-glass figures from the 1940s evoke Native American Hopi Katsina dolls and the designer’s own spirituality. The Carlton Room Divider, saturated and angular, recalls a man with his arms skyward, as if in rapturous prayer. Also on view is a never-before-seen collection of office furniture, originally intended for Mayer-Schwarz Gallery in Beverly Hills.

“Sottsass pieces are like interesting characters in a room that you want to talk to,” Graestch notes. “They catch your attention and make you think.” Nearly two decades after his death, the designer is still at the center of conversations—and collections.

in your life?

in your life?