In the staunchly competitive art world, it often takes more than talent, or even luck, to build a career. That’s where patrons like Suzanne Deal Booth come in. The philanthropist is nine years into the launch of her Suzanne Deal Booth Art Prize with The Contemporary Austin, reimagined and expanded in 2018 to become the Suzanne Deal Booth / FLAG Art Foundation Prize. Since then, the prize, awarded to one artist in the midst of a career-changing moment, has included $200,000, a solo exhibition premiering in Austin and traveling to The FLAG Art Foundation in New York, a scholarly publication, and a slate of related public programming.

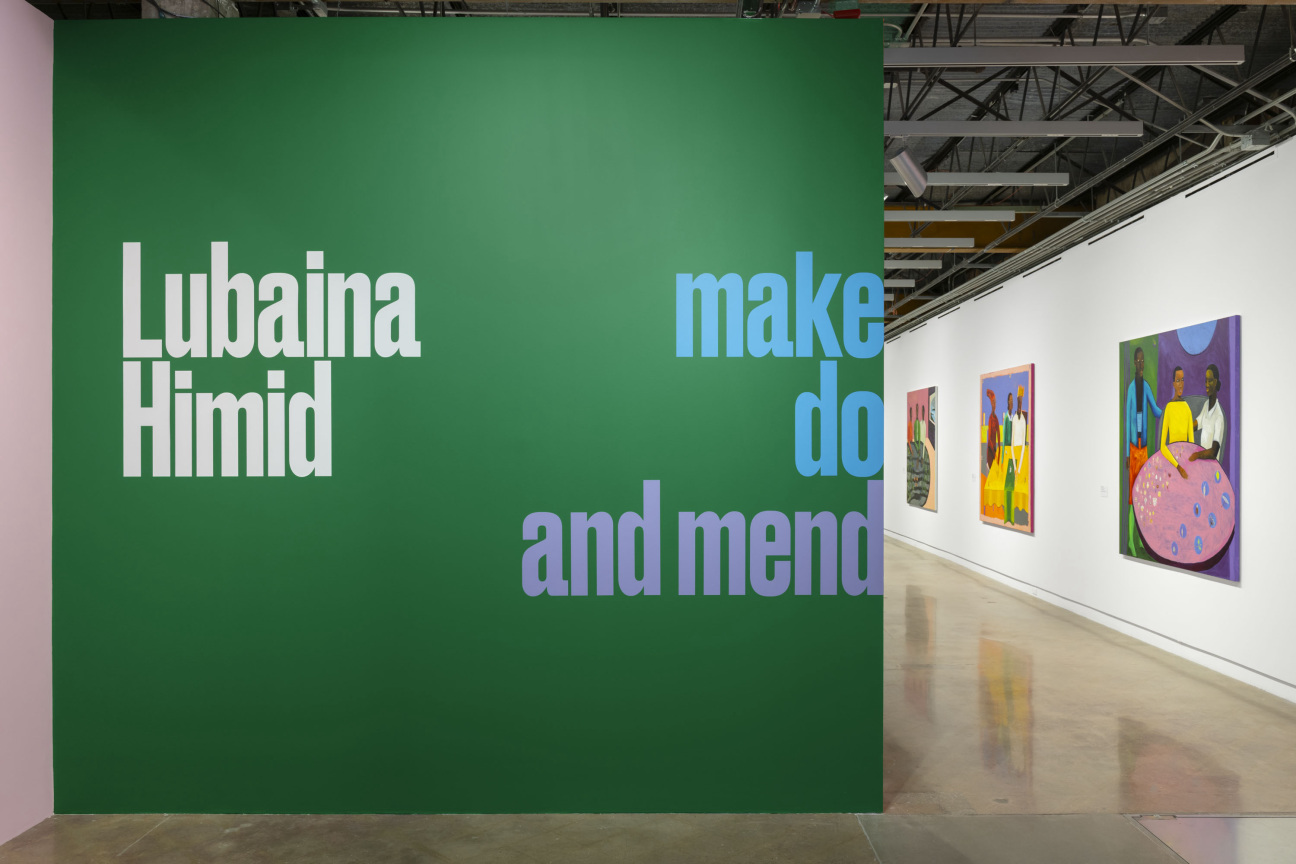

Earlier this year, Zanzibar-born and U.K.-based artist Lubaina Himid was announced as the 2024 recipient, and her corresponding exhibition, “Make Do and Mend,” is currently on view in Austin. After helping to usher in the British Black arts movement of the 1980s, Himid’s collection of paintings and found material creations received renewed late-career recognition when she was awarded the Turner Prize in 2017. She is now reaching further prominence Stateside with the announcement of this latest award.

The literature surrounding the Suzanne Deal Booth / FLAG Art Foundation Prize talks extensively of these “transformative” moments, when institutions and individuals step in to help usher artists over a hurdle—whether it be financial, social, or other. As that support is put to work for Himid, Deal Booth joined The Contemporary Austin’s Ernest and Sarah Butler Executive Director and CEO sharon maidenberg in a conversation about the power of philanthropy, and how it is best executed in Austin’s growing art scene.

sharon maidenberg: I always find it exciting and interesting to start with the history of the prize: where it came from; the idea; what inspired you to start this big, juicy, amazing award for artists, and especially here in Austin.

Suzanne Deal Booth: Well, at the time I had been in Austin about six years. When I came here, I got involved in The Contemporary Austin, saw it merge from one organization to another, and was also part of the process to bring the previous director here, Louis [Grachos]. I just felt that it would be something that would serve a few of the communities that are here and elsewhere—to bring an artist here to do a show, have lectures associated with it, visits from school children, have it up for several months, and give an artist an opportunity to do new work.

Austin really didn't have anything like that. Louis was keen on it. We tried to figure out the logistics. Should it be 10 years? Should it be biennial? What's the nature of the prize? What's the profile we're looking for in terms of who the artist would be?

maidenberg: In terms of how the criteria work and looking back at the artists who have won this prize in the past, one of the things that we think a lot about is transformation. What does it mean for a prize, or anything really, to be transformative for an artist? That criteria, which can be interpreted in a lot of different ways, how does that resonate for you?

Deal Booth: I think at the time it was and it still is, transformative—such a wonderful word. It means something is going from one place to another and changing. It also connotes that something really positive is happening, that if it's transformational in an artist's life, it's enabling them to do something they weren't able to do before, to reach a different community, and to perhaps get more exposure than they've ever had before.

maidenberg: I think about transformation, not just as change, but also as growth and new perspective. Sometimes you don't even know in real time how much you are being impacted by something. It will be interesting now, as we have opened the fourth exhibition associated with this prize and we'll soon be announcing the fifth recipient, to look back and talk to some of the artists who now have some perspective from it.

We just opened Lubaina’s show and, in my mind, one element of transformation is the chance to, as you said, make new work or try something new and different. We've got, obviously, the very beautiful paintings on the first floor gallery. The second floor gallery really is something quite new for Lubaina. She's created an arrangement of 64 plank paintings, titled "Aunties," that evoke the forms of East African funerary objects. What's your take on it relative to her other work that we know of?

Deal Booth: I'll start with the paintings—I thought it was stunning the way it was displayed in the space. The subject matter is so interesting. I noticed a lot of people just standing in front of the paintings, not quizzical but really trying to understand what story is being told, what the artist is saying.

On the second floor, what a surprise. She hasn't done anything like that: accumulating old boards from all over, different stockyards and renovated houses, and taking these boards and making a story that had to do a lot with her childhood, with people that she knew from Zanzibar. She herself said that this opportunity gave her a chance not to teach as much as she usually does to support herself, but to take some time off and to really have the freedom to think about new work.

maidenberg: The most poignant [work] tends to be when an artist can both tackle the most current issues of our time on a sort of geopolitical level, but also on a very personal, human, emotional level. These two bodies of work actually do that incredibly well. We share a belief that artists are such important storytellers and reflections of the world that we live in. I'm curious about your own take on the role that artists play in a larger kind of social context.

Deal Booth: It always depends on the artist, but artists usually are the voice of the moment. They're creating works that are expressing things that are happening in art, in real time, kind of like the news. By the time we see it, I mean, in this case it's just a few months. She just finished the painting the week before; the paint was still fresh.

maidenberg: Given that our building is just a few blocks away from the Texas State Capitol, it only feels appropriate to have an invitation to come and see what being surrounded by art does to a conversation, irrespective of the subject matter.

Deal Booth: I agree. For this recent opening, which is, of course, what we're remembering the most right now, we had so many international collectors, supporters, historians, dealers come in for that. The lecture you had at The Contemporary on the rooftop brought in the topic of what it was like for [Lubaina] when she was creating work early early on as a young woman, what was the climate in the U.K. when she started in her creative process, and the fact that she's been a teacher for so many years. It's really interesting where people are coming from.

Another strength of this prize is that we're able to understand how an artist processes and creates their work—not just the physicality of it, but what's going on in their mind as they are living the life they have in the sociopolitical times that they've experienced. Lubaina especially because she's a little bit older—I think she just turned 70—this is someone who has another 20 or 25 years experience than our previous prize-winners.

maidenberg: She's also now so internationally acclaimed, having been in the Sharjah Biennial, the Turner Prize, the Tate. I was just in London—she is all over the exhibition spaces there. It was interesting in her talk that she mentioned in some ways getting the Turner Prize was bittersweet in that she, if I'm remembering correctly, said that she felt so honored to receive it, but also felt like perhaps she should have gotten it sooner in her life and in her trajectory.

For me, as the institutional point of view, I feel very gratified by the true diversity and range of the artists who have received [our prize] because each one is really their own sort of snowflake, right? I do think it's important to note that the jury changes every cycle. There isn't an institutional taste necessarily. It's really driven by what I like to think of as a selection of some of the most interesting thinkers, curators, directors working today. Is there anything you'd say you've learned from the prize, the process, the selection of artists over the last eight years?

Deal Booth: There's been change over in staff, there's been change over in people who are in charge of making the prize happen. The two consistent people have been myself and Glenn [Fuhrman, founder of the FLAG Art Foundation]. We’ve become the corporate history of the prize.

What we have to say during the jury, even though we're not voting, it makes a difference because we can tell the group what previous shows were like and how they check the boxes of being transformative or transformational, either for the institution or the artist. I have found that I have a more valuable role than I thought I would. I think Glenn would have to agree that suddenly it's what we remember about these exhibitions and how they worked and these shows that makes a difference.

maidenberg: You both are so good at showing up and being present in the room but not heavy-handed in the process, which is really important for people to know how this artist is selected. You and Glenn are really, at least from my perspective, really engaged, thoughtful art world opinion havers. I think of some collectors as folks who really just love the objects and then I think of some as truly caring about artists, and you both really care about artists.

in your life?

in your life?