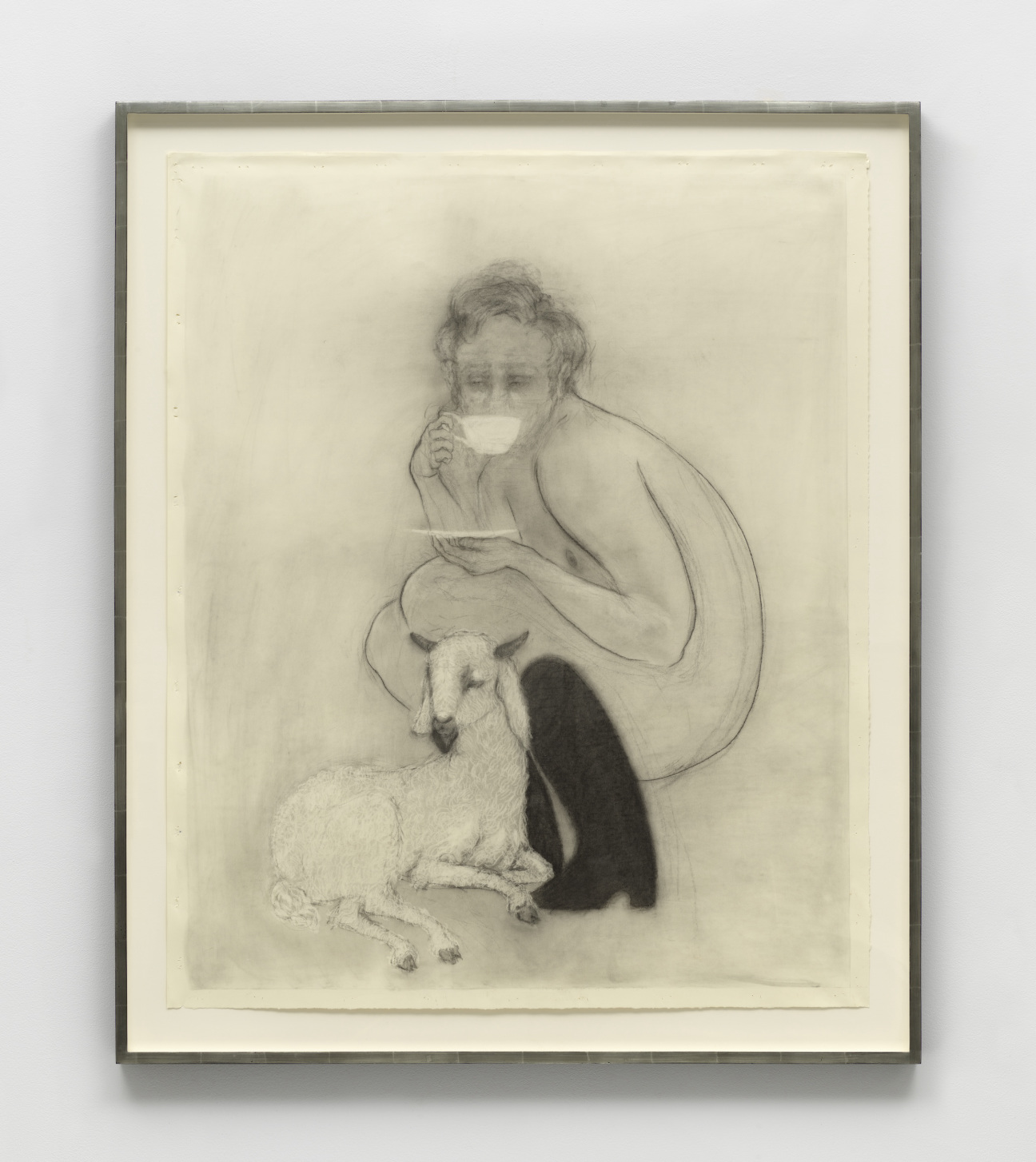

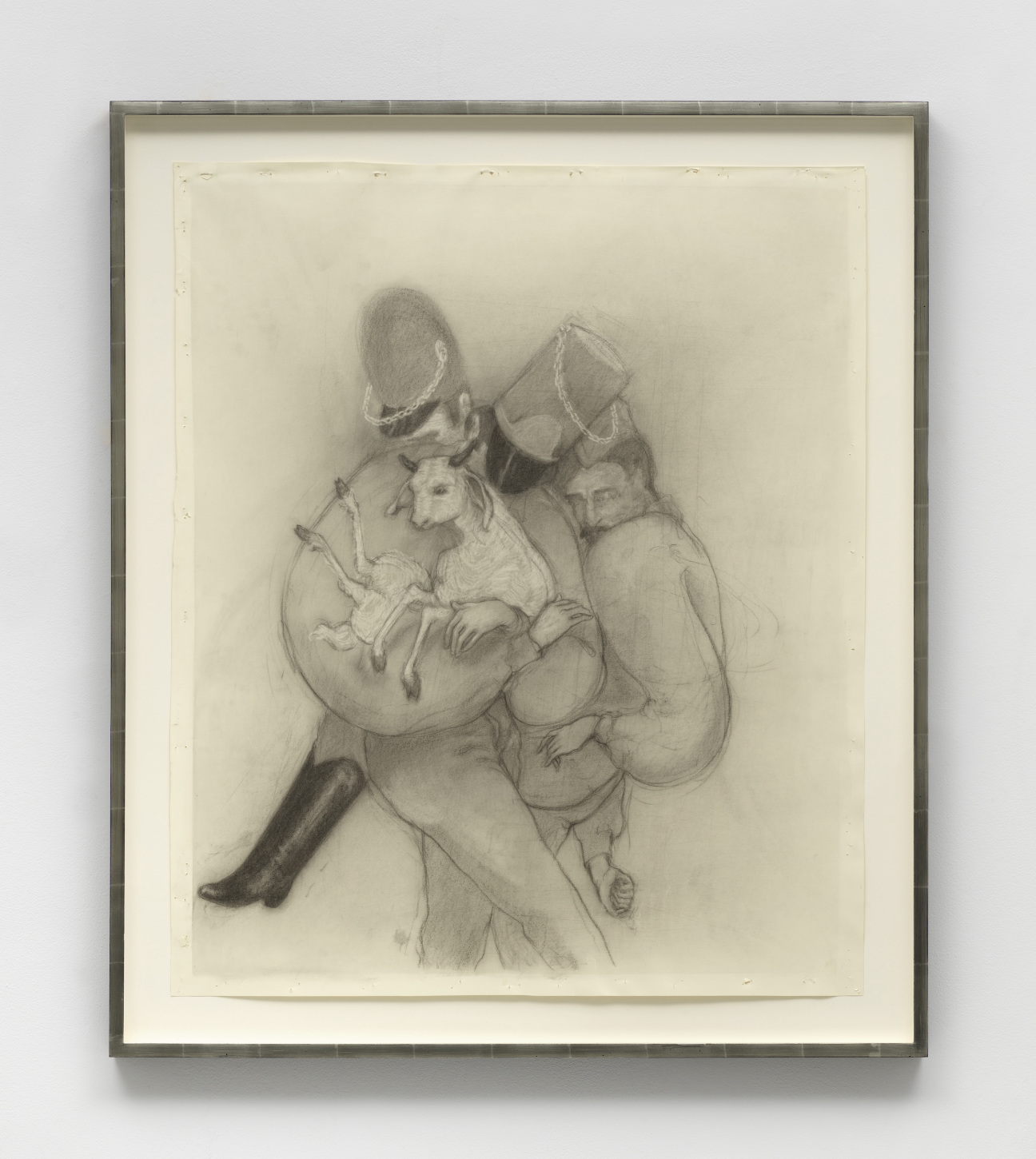

Jared Buckhiester’s narratives are always a bit peculiar. Whether through drawing, sculpture, or video, the multimedia artist upends expectations. Marrying inspiration from his childhood in Georgia with a queer bent, there’s an out-of-placeness to his figures, either in their surroundings or their own bodies. In Glory, 2008, an almost-nude man pulls his shirt over his head, obscuring his face as he arches his back against the front of a dilapidated house. Action Figure Variation One, 2012, traps a running man in papier-mâché, the head and right knee removed to reveal the hollow inside. Combining the unexpected and suggestive, Buckhiester’s gaze allures, repels, then calls back once more.

Friend and collaborator Hilton Als has noted the “off-kilter” way the artist looks at his surroundings. The Pulitzer Prize-winning author of White Girls and My Pinup brings his own tilt to the world, blending memoir with astute criticism in a way that has made him a standout cultural voice. Recognizing a kindred quality in Buckhiester, Als has become both a collector and curator of his work.

With the artist's latest show “No heaven, no how,” Buckhiester embraces his signature oddities. His figures squat completely naked in knee-high boots or cover their faces with hats, at once adding and obscuring meaning. Curated by Als, the exhibition is on view March 23 through April 27 at David Kordansky Gallery in Los Angeles. Ahead of the opening, the artist and writer sat down to discuss leaving the South, alternative educations, and the allure of a good boot.

Hilton Als: Tell us how the show came about, Jared.

Jared Buckhiester: I came to hear Jason Fox's talk at Kordansky. [As] I was leaving, someone goes, “Jared,” and I turned around and it was David. He explained, “I was looking at your sculptures on Instagram, and here you are in the gallery.” He said, “Let's do a show.”

Als: When you first started making art, how old were you, and what kind of work were you doing?

Buckhiester: As long as I can remember. I knew that I was good at drawing, so I would draw things around me, like a boot or my dog, or unicorns. In a Christian home, you want to draw things that are really upsetting to your mother. I'd hide all these drawings in the closet of babies on crucifixes.

Als: You grew up in the South, and one of the things that interests me about the South is the innate Gothic element in terms of hierarchy and families. What was that like growing up?

Buckhiester: You don't really see it until you leave, and then you start to recognize it in fiction or movies, and you're like, “Oh, I knew that firsthand.” I would watch Hush… Hush, Sweet Charlotte or To Kill a Mockingbird on Saturdays instead of cartoons. It's an affect that, for better or worse, I'm drawn to.

Als: Were you always intent on leaving that place to come to New York?

Buckhiester: New York was where the kids I met the summer between my junior and senior year were all going. I'd been running away to Atlanta since I was 15, and I knew it was too small. I went to this summer college program, and all these friends were moving to New York. I was like, Oh God, that's what I'm going to do.

Als: When you were running away to Atlanta, what were you doing?

Buckhiester: Oh, all kinds of things that needed to be explored. It was the ‘90s. I was gay. I had no idea that there were other gay people. I needed to find them, and I found them.

Als: What was that emigration up north like?

Buckhiester: I was so glad to be that far away from the constraints of what I left. It was ‘95. I moved here with a friend, but he didn't want to go to Wigstock the first weekend. I was like, “Well, I'm going by myself.” I went and met a group of friends that stayed my nightlife friends for the next four years. The culture shock was going back. There was a certain amount of how do I fit in, but also how do I surround myself with the things I'm interested in? It was nightclubs and people that I'd seen in magazines, that kind of excitement.

Als: Did it feel like the "Let's All Chant" scene in Eyes of Laura Mars? What kind of classes were you taking?

Buckhiester: I was just in class to be housed. My mother was like, “If you're going to go that far away to school, you're going to a school with walls around it.” Pratt was the only school with walls, but it was in Fort Greene-Clinton Hill, which was very dangerous at that time, but it was really thrilling. It was art school, so you could do whatever you want and still get an A. I was in photo classes mostly.

I’d take photographs in nightclubs and use that negative for every photo class, so I could get away with doing as little work as possible. Then I was out of school for 10 years. I didn't even really start looking at art until I was in graduate school [at Bard]. All my information came through movies, and books, and friends who gave me books. Even though I was showing in Chelsea, I barely went to look at art. I really was trying to keep it a secret that I didn't know how to look at abstraction in grad school.

Als: In those 10 years, what were you doing?

Buckhiester: I was making drawings, showing and selling them, making porcelain sculpture. But I was making the same work over and over and couldn't figure out why. Bard was the only place I applied. I was friends with Hudson at Feature Inc., and he wrote my recommendation. It was one of the hardest things and also probably one of the most important things that I did.

During a music sound performance, there was this pivotal moment. Sergei Tcherepnin—his grandfather created the surge synthesizer—was doing a performance and had rolled out this piece of aluminum on these auditory vibration elements. He was crawling in slow motion, and it looked like he was sprinting. The sound was like applause and a wave and a cheer all at once. I was like, “That is like the power of a suggestion rather than a closed narrative.”

Als: How did that experience influence the art you were making at the time?

Buckhiester: I started working much looser and in fragments. I made a film with Dani Restack called Hard as Opal. It was film as fragments but with so much information in them. Whereas before I was making a very tightly rendered narrative, bucolic landscape with people in it and these porcelain busts, I [started] making photographs of truck drivers and ceramic forms to go with the photographs. The object itself was either a fragment of time or an imagined fragment of artifact. Those two things put together created a new space of trying to understand the two in relation to each other.

Als: What were the artists that you were looking at that time?

Buckhiester: You used Flannery O'Connor for some of the wall text: I was reading Mystery and Manners. I was reading Logic of Sensation, which is [Gilles] Deleuze's text on [Francis] Bacon, and I was reading the David Sylvester interviews of Bacon. All three of those are talking about sensation as understanding. Approaching a work of understanding through sensation rather than through the mind. So it was really exciting to have those guides.

Als: A lot of the work does tell stories, but they're off-kilter. Why do you think that narrative has a hold on you?

Buckhiester: The fragment of a narrative is such a quick way into subconscious associations. I get so excited when I'm placed in a space in my mind that is intentional but I didn't plan to go there.

Als: The story that you're telling is so unexpected that I like the feeling of giving up on traditional narrative expectations. The work works in collaboration with the person. It's a wish.

Buckhiester: It’s a wish. I try to trust what gets me excited in the studio. If something's done and I've placed it next to a drawing that I've made, when it starts to bounce back and forth and I start seeing things that I didn't expect, it's on the right path. It reveals itself a month later, sometimes two months later, but once it reveals itself as so obvious, it's exciting, because the instinct is below consciousness.

Als: When I look at some of the drawings and sculptures, there's such an incredible eye for costuming. Boots and hats: it reminds me of the first Prada show I ever saw. People were so outraged [Miuccia Prada] had C.Z. Guest in boots. How do you decide on what they should be wearing?

Buckhiester: It’s my gut instinct. The hat had become this thing to obscure a face, but it's also this idea of they're all just playing dress up. And disco matters. It's like, This is so heavy, there needs to be a little disco here somewhere. The posing with the costuming also upsets the references a little bit with the drawings. If I'm drawing a patent leather boot, then I can go really dark instinctively. I won't tell you why everything gets a bootie. I don't fully know. I just love those boots.

Als: It's like Cinderella for men. You lived for a little while abroad in Europe.

Buckhiester: I did run away with a shoe designer, actually.

Als: There it is. When was that?

Buckhiester: Around Y2K. We lived in Milan in a tiny apartment. He was gone all the time, so I basically lived there alone. I taught myself Italian. I had two friends that I made while I was there. Three, actually. I was there for four months. I don't want it to sound arrogant, it just feels really natural in a weird way. The way that I met David [Kordansky] felt really natural. Then doing this with you feels like an extension of a relationship that's grown in ways.

"No heaven, no how" will be on view from March 23 through April 27, 2024 at David Kordansky Gallery in Los Angeles.

in your life?

in your life?