In 2017, playwright Tina Satter discovered the transcript of an FBI interrogation. The transcript became the backbone for Reality—Satter’s first film, out last spring—which charts the true story of NSA whistleblower Reality Winner. The thriller mines the encounter’s inherent absurdity—a yoga-and-gun-loving 25-year-old translator’s prolonged encounter with two bumbling agents—without veering from the simmering tension that undergirds it. Here, Satter reveals an artistic inspiration that illustrates the ominous, unresolved emotions at the heart of the film.

CULTURED: What jumped out at you when you first discovered the Reality Winner transcript?

Tina Satter: It struck me that this young woman was holding, in her identity and background and actions, something at the cross section of the America of that moment. Like what it would mean if you were a gun owner, or what it would mean if you were the kind of person who taught yoga. She held all of this in her life and then she engaged in a call-out of our government, right? What it meant to be an activist and do all that was so irresistible to me. And because of the interrogation, we have her words from in this completely banal-seeming but utterly life-changing moment. I was like, "Oh my God, that is just really wild that we are in that room with her."

CULTURED: You turned the transcript into a play, "IS THIS A ROOM" in 2019. How did Reality evolve from a theater performance to a film?

Satter: When I first stumbled upon that transcript, the first few minutes of scrolling through, I was literally on the edge of my seat. It was like, "Oh my God, this is so weird. This looks like a play. This is my speed thriller." And I hadn't made a full feature. Some small video projects were all I'd done at that point. But I'd been very curious about it, and I had this instinct, even then, that this was a movie I could see and feel.

For the stage play, I knew I didn't want a literal set of something inside her home or those rooms. That's not really in my general theater aesthetic. I was interested in something much more abstract to hold that conversation. Then I started to look at her Instagram that had been up until the day she was arrested. Just seeing the ephemera of her young womanhood, and the house she was in, was always so interesting to me. So as a movie, I was so excited to show all that takes place at her home.

CULTURED: When did you first see Virgin and Child Enthroned with Four Angels?

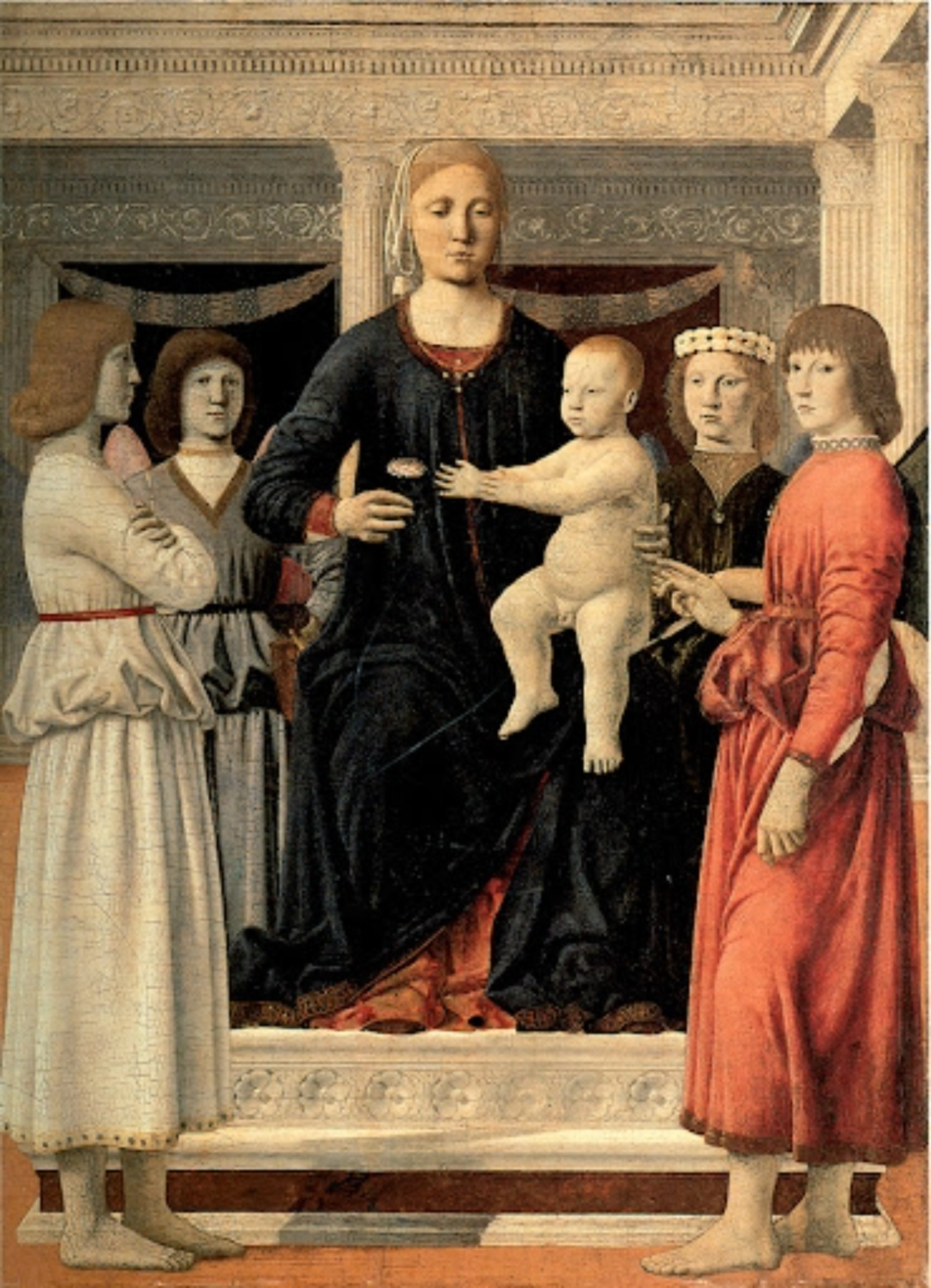

Satter: I first encountered Virgin and Child Enthroned with Four Angels [1460-70] around 2017. Jerry Saltz wrote about Piero della Francesca, and I was watching all these YouTube video lectures on the Renaissance. So often these paintings have a haunting, fascinating quality to them. In this one, it feels like so much more is going on—like there's an iceberg underneath each of them.

All the figures have feelings behind their faces, and that was going to be the "lingua franca" of so much of the emotional trajectory of Reality, that just under-the-skin thing, for Sydney [Sweeney’s role as] Reality, but also for the FBI investigators. They’re not in a neutral room at a police station or FBI office. I’ve always imagined that in real life the agents were like, "Oh my God, we’re actually in this girl’s house right now."

CULTURED: What drew you to the Renaissance in particular?

Satter: It's just so satisfying to me. Each painting feels like a play. Even with a portrait you're like, "Oh, this person is literally [giving] a monologue." They're just vibrating with so much life.

CULTURED: When did you know this painting in particular would work its way into Reality?

Satter: Well, it's a picture I had meditated on before for a play that's quite different than Reality called House of Dance. The whole play was set inside a tap dance studio with four people. That was around the time I came to this painting in the first place and was like, Oh, this is really helpful for me.

Jump to Reality years later, and I'm starting to meet with the DP Paul Yee. We had this back room [that most of the film is set in], and I really wanted to keep it as plain as possible to keep it true to life. That challenge of, can we activate the realism of it that way? And what do I keep thinking of but that Piero della Francesca painting. As soon as I looked at it, I was like, Oh my God, there we go.

CULTURED: What parallels do you see between the painting and the film tonally?

Satter: The color palette. The FBI’s colors—tan, navy, and pops of yellow—were always very exciting to me because it's just so specific. Then it weirdly matched that Reality was wearing her yellow Converse, which are her go-to. And this figure on the left of the photo literally could be Agent Taylor, standing there with his arms crossed and so. In the painting, it really feels like something's going on for each of them right behind those eyes or behind those implacable faces.

CULTURED: How does looking at this painting make you feel?

Satter: It just makes me lean forward and want to know what's extending in the air behind each of these people's heads, their personal subtext. So much more is going on than just watching this child. And that feels really inspiring to me. It just feels so loaded in ways that I don’t even know.

This conversation is part of a series in which CULTURED asked filmmakers to reflect on a work of art that exposed them to new ways of seeing—and set the tone for a recent project. For more insight, read Lulu Wang on the Singaporean photographer whose work inspired both The Farewell and Expats, or Cord Jefferson on how Hollywood Shuffle helped shape American Fiction.

in your life?

in your life?