In his last semester of undergrad at Ohio Wesleyan University, when his classmates were starting to pack up their studios and indulging in cases of senioritis, Andrew Wilson embarked on a photographic journey. The art student was working through the legacies of artists like Roy DeCarava, Robert Mapplethorpe, and Glenn Ligon and what these image-makers made of the Black male form. What would it look like to dialogue with—and challenge—their ideas in 2013?

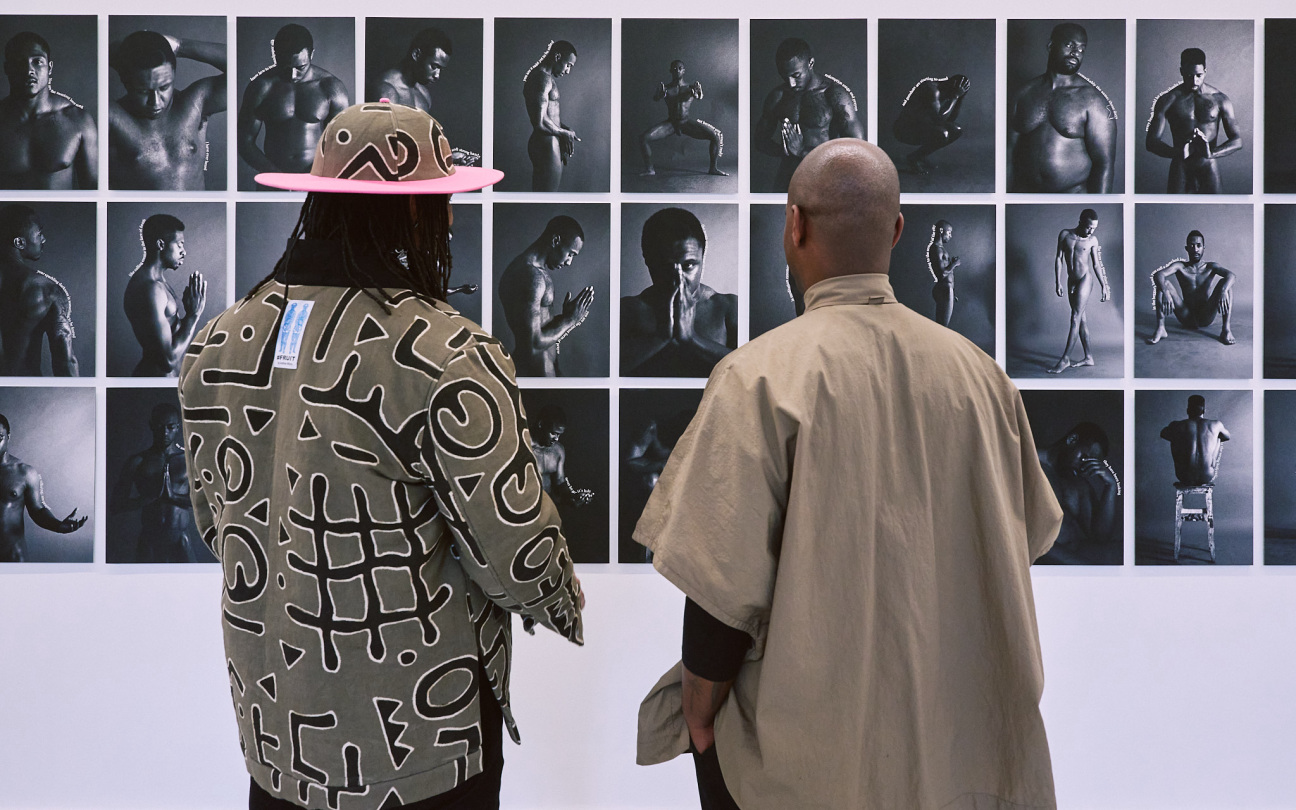

Wilson began asking peers, first among them the university's football team captain, to pose for a series of photographic reflections that would unspool and complicate the visual language associated with Black men. Eleven years later, the moments of reverence and release Wilson fostered in these sessions are on view through March 16 in "Torn Asunder," an exhibition at San Francisco's Jonathan Carver Moore gallery. Below, the artist charts the project's path and unpacks the human and technical elements that informed each image.

CULTURED: Tell me about the genesis of “Torn Asunder.”

Andrew Wilson: “Torn Asunder” is the second iteration of the project “Temptation of One Dark Body,” which originally was a book. I was doing an independent study with art history and photography at that time, where I was looking at queer contributions to the Harlem Renaissance. From there, I stumbled upon Roy DeCarava and Langston Hughes’s The Sweet Flypaper of Life, a gorgeous collaborative work that they did. I was also looking at Robert Mapplethorpe and Glenn Ligon's critique of Mapplethorpe in his “Notes on the Margin of the Black Book.”

The question that came up is what's the legacy of this kind of inquiry? So I put together this idea that I would make a book in conversation with DeCarava and Hughes, thinking through Mapplethorpe, but Glenn Ligon as well. How to imbue the Black male form with introspection, meditation, and prayer—things that generally the Black male form is deprived of, if that's the best word for it. I first approached [my friend] James, who was the captain of the football team at the time. I was like, “If I can get James to do it, I can get everyone else to do it.” He was dating a good friend of mine at the time. We had become, you know, really close. I pitched the idea to him, and the first thing out of his mouth is like, “Yeah, of course.”

CULTURED: How did you react?

Wilson: I'm a very queer man. I think only one model was queer; the rest of them were all heterosexual, right? And I'm like, “Okay, I'm going to ask Black heterosexual men to pose nude for me, being extremely queer. Shit.” That's a lot of responsibility to hold. Then on top of that, in the production of the images and thinking about where they'll go after, that’s another kind of massive amount of responsibility.

CULTURED: How did you reckon with that during the shoots?

Wilson: As they entered the studio, I had a pile of books. They were all marked with images, some inspiration, so they could see what I was going for. I also made it very clear that I was never going to touch them; if I needed something demonstrated, I would show them and then they would just copy me. I was like, “Okay, you gotta take all your clothes off, and I'm here. Yeah, I know this is weird, but it's okay. It's going to be weird for like 10 or 15 minutes and then you'll forget that you’re nude.”

CULTURED: How did they receive the pictures when they were out?

Wilson: I showed everyone their film. I got them together one by one, and I was like, “Look, these are your images.” They were pleasantly surprised. I was trying to sell the books for $100 a piece, and nobody wanted them. No one at all. I was like, “I think it's really good, but alright.” They sat for years, and I would come back to them annually, going to the folder and picking a couple images and editing them a bit.

CULTURED: How did they resurface?

Wilson: It was maybe 2020 or so as we hit pandemic time. With a couple homies, we would be on Instagram, video chatting and baking. One day I was like, “I have something to show y'all.” And they were like, “What the hell? Why are these just files?” I was just going to let them sit forever … Initially I was talking with a gallerist about the work. I sent them some different files, and they shopped them around to some of their folks. They said that the response from their folks was that the work was reductive. I've never said that this work is anything other than it is. The legacy has always been clearly laid out. I've never tried to claim to do anything new with the work, so I was just very confused by this idea that it was reductive.

Then I was talking with my friend Dimitri Braxton over at MoAD, and he was telling me about Jonathan Carver Moore because he was going to open his gallery. We started this conversation last January before he even opened the gallery. We had tea, and I was like, “I have a lot of mistrust around gallerists and the monetary arm of the art world.” As someone who is a multimedia artist, I've been told on a number of occasions, “Oh, we have to show this body of work and just wait to show something else, because we have to establish you as kind of one thing.” That's not how I operate. My question to Jonathan was, “What if we do this show as photographs. Then the next show is shoes. After that is jackets, and after that is a performance.” He was like, “Yeah, I don't understand why you can't do that.” That was just so liberating.

Andrew Wilson's Walk-Through of "Torn Asunder":

“This is Temptation of One Dark Body. At the opening, I remember there were folks asking me, ‘Why do some of the images have text and some don't?’ I'm like, ‘What are you talking about? All of them have text.’ The words on the images are a 42-line poem, or 42 one-line poems. As I was working on the contact sheets and scanning all of the images, the poem emerged at the same time. Many, many years ago I was a slam poet. That's where that kind of inquiry comes from—language as an intervention. But the challenge with language, especially on images, is, it'll flatten them. I was looking at Roy DeCarava’s The Sweet Flypaper of Life, where the text is below the image, and I was also thinking about Carrie Mae Weems’s 'The Kitchen Table' series. I've worked with Carrie since 2019 or so. I'm on her exhibitions and install team. So all of these conversations are happening at the same time. The idea was that if the text can exist on the contour, that changes the relationship to the figure. It softens the text in a way.”

“During the photo shoots, I was using both medium format and 35 mm. With the Yashika 635, you have to hand cock the shutter every time, so these were all happy accidents. None of these double exposures were on purpose. I didn't even know about them until I scanned them. Maybe it's about being lost in the process, engaging in the conversation with these folks. During the photo shoots, the first half or so I had a set of poses to help them kind of get in their own bodies. And the last half, I'd say, 'What is something you've always wanted to do that you never thought you would ever be able to? What does that look like in your body? You get to be that right now.' There's a poetry that's happening in this image where the pec becomes the eye, and the leg becomes a second arm. There's so many juicy details, and there's also no bright white in any of these images. So they're so rich and so dark that it calls one to be still. Dom is the coolest dude ever. He's a lawyer now. This is the soft side that I don't know if anyone besides possibly a romantic partner would see.”

“Garrison is the sweetest dude on the planet. He's in renewable energy for low income folks; that's his thing. This image is almost the title work for the show. It identifies what the dualities can look like, right? It's surrender and contemplation, protection and relaxation. It's love and care, but it's also like 'Stop outside world.' The first thing I think about is the hand at the bottom of the image. That part to me is just divine. I've realized over the last 10 years that the core of my work is subtlety. Like, how do we invite the viewer in? And in that invitation, how is the viewer then implicated?”

“I do have to make sure that I always give thanks for James to be so instantly game to be vulnerable, but then also to act as a liaison. I was asking these other folks [to participate] after he did the photo shoot, and they went to him and were like, 'Yo, how was it? Was it weird?' He became the liaison for this project in a really incredible way … The figure is never directly engaging with the viewer in this image, it’s very closed. I love how the bicep becomes a scapula. And then if you look at the hand that becomes the knee, you also see those are little friendship bracelets that you wear until they fall off. It's those just gorgeous, tender moments. When I walked into the gallery, I was so overwhelmed because it just oozed with this quiet care that I was hoping for so many years would happen.”

“Nginyu and Dom are the only two that directly engage the viewer. This was definitely Jonathan's favorite image. When he first saw this image a year ago he was like, 'I want that. You could pick whatever else you want to pick, but I want that one.' I haven't spoken to Nginyu in many, many years, but he was the coolest dude. He was able to float around any group of people and be the most loving and tender human. This image is probably one of the ones that most directly quotes Mapplethorpe. The figure on the stool faced away; that's a Mapplethorpe icon. How do we take that icon and maintain criticality and care? That's possibly what's happening here. The stool was from the painting studio; you can see all the paint on it. But if you look at it on the right corner, there's a fake flower. It's those little moments that just get me every time.”

“I think Vaughn still lives in Ohio. He's a workout guy from what I have seen on his Instagram. In undergrad, he did not like me at all. I was just always confused, like where his homophobia comes from. In my last semester, I had to take computer science. It was me and my friend Logan in the class with Vaughn. Initially I approached him and I was like, ‘Yo, I think that this opportunity would be incredible, not only for you but like for this project. It would be extremely liberating.’ He hemmed and hawed for a couple of weeks. And after some time he finally agreed, and I think that his film came out the most incredible. He was able to suspend his disbelief and really lean in in the most amazing way. This image I think really speaks to that. You have the V in the center of this image, then you have an upside down V with the leg that's up. I'm just so thankful that he was able to lean into freedom, right? The hope of this project was to provide that space for my homies, and they all went for it. They are committed in ways that I never could have imagined.”

"Torn Asunder" by Andrew Wilson is on view through March 16 at Jonathan Carver Moore in San Francisco.

in your life?

in your life?