How does an artist continue to make work after years behind bars? Jesse Krimes, founder of The Center for Art and Advocacy, sought to answer this very question after spending six years in prison. Inspired by the creative community he discovered while incarcerated, the Philadelphia-based artist set out to provide a path to reentry for formerly incarcerated artists, one that would help them amplify others seeking a bridge to community along the way.

Initiated in 2017, the Right of Return Fellowship (ROR) is the first of its kind, offering dedicated resources and mentorship to formerly incarcerated artists along with an unrestricted grant of $10,000 and an additional $10,000 in project development support. Now ushering in its sixth class—artists Antwan Williams, Gary Tyler, George Morton, Kendra Ware, Omari Booker, and Rashaan Thomas—ROR continues to fight not only for a sustainable, equitable path forward for those impacted by the justice system but also to shift the larger narrative around mass incarceration in the U.S.

Drawing from his own experience, Krimes speaks to CULTURED about the fellowship’s larger goals, the importance of community, and the exciting year ahead for The Center.

CULTURED: What is the CfAA’s process for selecting artists for the fellowship each year?

Jesse Krimes: Applicants are reviewed by an external committee of curators, artists, filmmakers, poets, and other experts in the field. The reviewers represent diverse geographies and backgrounds, and they change every year. All applicants are pooled in their creative disciplines and reviewed by discipline-specific experts to arrive at a short list of 40 semi-finalists. The semi-finalists are then shared with the full committee. We ask reviewers to independently select and rank their top six candidates in order according to our selection criteria: 1) the quality of artist’s past work and proposed project, 2) the likelihood that the award will result in the production of artistic work that will meaningfully contribute to criminal justice reform efforts, 3) plans for public engagement in the work and its intended audience, 4) the likelihood that the proposed work will be completed within the timeframe and budget, and 5) the diversity of the finalists pool. The final rankings are compiled in conjunction with the review committee to select the final six fellowship winners.

CULTURED: What makes this year’s group unique?

Krimes: We have a great geographic mix of artists across the country working in various creative disciplines to address issues of mass incarceration. As we think about supporting artists and potential impact in changing national narratives around this issue, it's vital that we are able to support artists from some of the most impacted communities in the country.

CULTURED: Each of ROR’s fellows is working on their own project in their specific medium, but do you see any opportunity for collaboration between the artists?

Krimes: While all of the artists are working on their own independent projects, they are generally unified around the core theme of ending mass incarceration. This creates an endless array of possibilities for collaboration, especially across disciplines. While we encourage artists to create the project that they believe will be most impactful for themselves and their larger goal of changing the narrative around issues of incarceration, we also intentionally foster community and opportunities for them to meet their fellow cohort as well as the larger Right of Return alumni community during our annual retreats. Ultimately, artist collaborations must arise organically of their own volition, but we create the opportunities for those collaborations to take root.

CULTURED: What impact have you seen come out of the work created by the fellows?

Krimes: There are innumerable ways, both large and small, that our fellows have created tangible impact. Since the fellowship’s founding in 2017, our fellows have significantly contributed to the shift in public narrative and challenged the ethos of disposability that undergirds mass incarceration. Through the creation of highly visible projects, they've engaged communities across the country, fostered often difficult dialogues, garnered significant press and awards such as the MacArthur Award and Pulitzer Prize, and highlighted the value of people who have been incarcerated. The groundswell of visibility and amplification created through this artistic community has helped to lay the groundwork for major art foundations, funders, and institutional partners to join the movement. This collective community has made a once mostly hidden and ignored issue into one of the most talked about issues facing our country's pursuit of equity and racial justice.

CULTURED: How have you seen incarceration impact the careers of artists involved in the program?

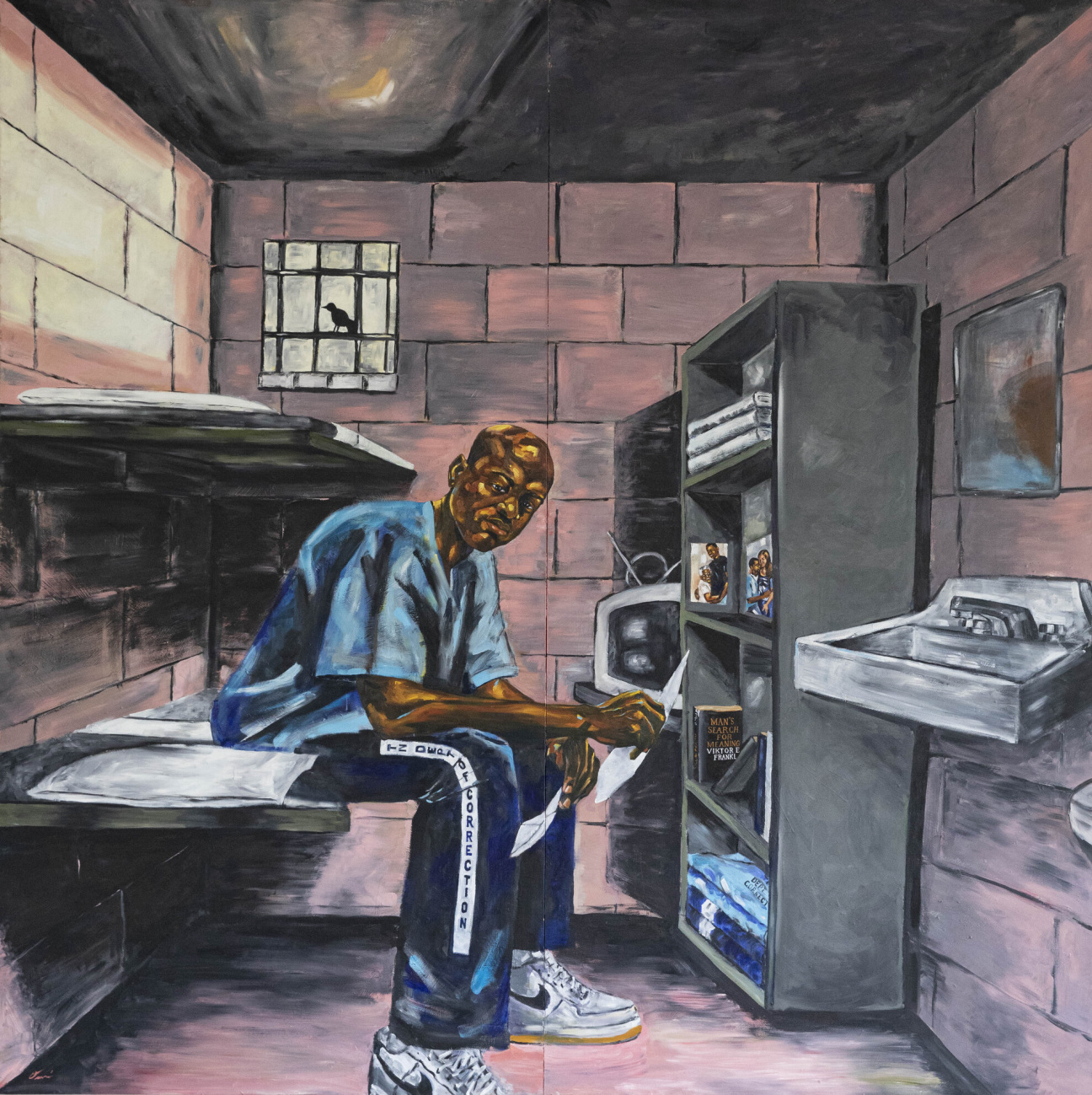

Krimes: We are working with a population of people who have lost years, if not decades of access, artistic community, and support as it relates to gaining traction in the art world or other creative industries. It is difficult for any artist to make a career and survive, but when you compound those difficulties with the barriers imposed by incarceration, it makes that pursuit infinitely more difficult. While incarcerated, artists face censorship on what they are allowed to make. The sheer loss of time, access to materials, and artistic community means many of our fellows are starting to pursue their careers much later than their peers in the free world. Even basic access to education and technologies like computers and smartphones hinders our fellows' capabilities and understanding on how to write artist statements, apply for grants, research their interests, and more generally use technologies in ways that most people take for granted.

After people return home, they also face housing, employment, and travel restrictions in addition to being surveilled through probation and parole, plus forced to pay fines and fees, which puts an inordinate amount of pressure on people's resources and time. We have also seen how the trauma of being incarcerated has negatively impacted our fellows in a variety of ways; however, the primary impact we have seen is how the experience has created an unrelenting drive and ingenuity within our artists to not only create unique works of art, but also to create works that both challenge the barriers they face while showcasing the value of people who have been incarcerated.

CULTURED: How did your personal experience reveal a need for a program like this one?

Krimes: While incarcerated for six years, I was consistently blown away by the ingenuity, creativity, and brilliance of the people I was locked up with. In every prison I was housed in, there was a vibrant and well-respected community of creatives making incredible works under some of the most restrictive and traumatizing conditions, completely isolated from the creative communities outside prison walls. When I first came home from prison in 2013, there were no programs or institutions that I was aware of that supported formerly incarcerated artists as serious art practitioners, and most of the existing programs were clearly not designed to support the level of criticality and talent that I had witnessed while incarcerated. As I began to build my own career as an artist, I noticed how I was often the only formerly incarcerated artist being included in exhibitions around themes of incarceration. Seeing the gaps in existing programing and institutional structures, paired with the direct knowledge of the immense wealth of creative brilliance locked behind walls, it was clear that a program like the Right of Return Fellowship was vitally important to center the experience of people who have been directly impacted by incarceration.

CULTURED: How has interacting with the fellows influenced your own art practice?

Krimes: Being a part of this creative community has provided invaluable support and expanded my insights into the many facets that surround and sustain mass incarceration. These insights have allowed me to sharpen my creative approach in engaging audiences around issues of incarceration. Interacting with the fellows has also encouraged me to be more collaborative in my creative process.

CULTURED: What are your goals for CfAA’s programs moving forward?

Krimes: We've found that justice-impacted artists within the U.S. continue to be under-funded, under-mentored, under-resourced, and under-connected.This is why The Center for Art & Advocacy is building upon our catalytic flagship Right of Return Fellowship to provide additional financial and community support. The newly launched Center will bring mentoring and professional development to scale through our capacity-building Academy program for emerging impacted artists. We will also dedicate time and space for creation and multidisciplinary collaboration between artists and advocates at the Center’s Residency in rural Pennsylvania. To ensure that our artists will continue to have dedicated space in the art world, our gallery in Brooklyn will open in Spring 2024 to showcase our artists’ work and relevant programming. These distinct facets provide entry points and support for formerly incarcerated artists at every stage of their career.

As we more expansively support existing fellows, we are also balancing an overwhelming demand for a limited number of fellowships. Each year, we receive over 300 applications from exceptionally talented artists, and inevitably, our rotating panel of expert external reviewers must turn away applicants. The Center’s vision is to serve as many justice-impacted artists as possible with powerful and transformative programming. We hope that interested supporters and partners will continue to champion this movement, built by artists for artists.

in your life?

in your life?