Pippa Garner has held a zany mirror to American consumerist culture for over 50 years. Her inventions—high-heeled roller skates, escalator stepladders—are wry parodies, situating her in the vein of absurdist icons like Meret Oppenheim and Andy Warhol.

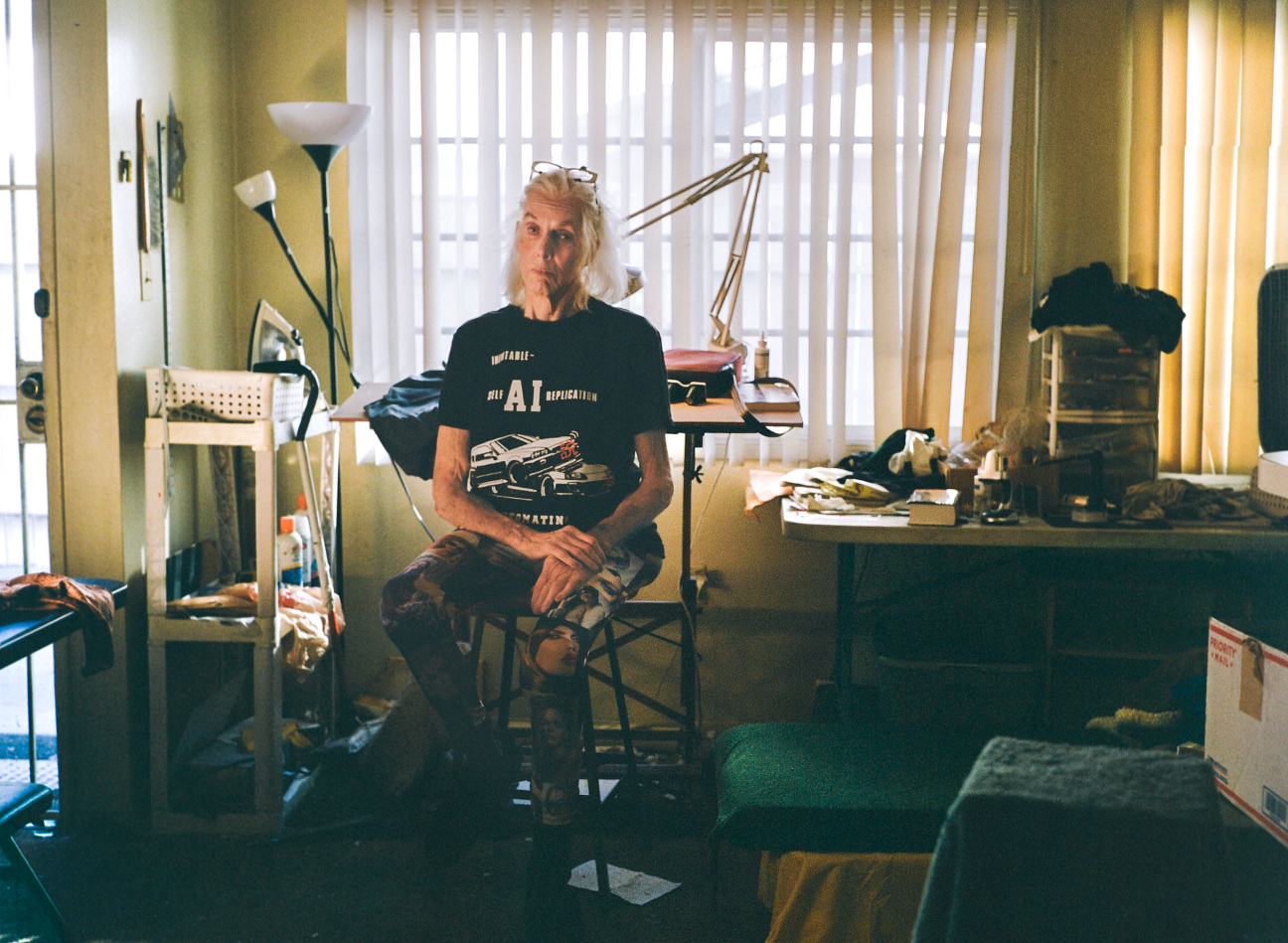

Garner spent her career relegated to the art world’s periphery—perhaps a result of her experiments with “gender-hacking” in the early ’80s. But at 81, Garner is finally getting her flowers, and she has a string of recent exhibitions (her first solo museum show at Art Omi, an appearance in the Hammer Museum biennial, and a show at White Columns) to prove it, along with her first comprehensive monograph, Act Like You Know Me, out this week.

CULTURED: What was your first taste of the art world?

Pippa Garner: I don’t have a moment I can describe like that; it just evolved. Being in the art world, as it were, kind of descended on me. I was amusing myself and following through with ideas I thought had to be done.

CULTURED: Is there a moment in your life that shaped your understanding of what an artist is?

Garner: The first well-known artist I had any real contact with was Ed Ruscha, way back in the '80s or '70s. His studio was not far from where I lived, and we would have dinner once in a while. He was five years older than I and was well established then. My first opportunity with publications was with West Magazine, the Sunday magazine of the LA Times, which no longer exists, but it was wonderful.

Mike Salisbury was the art director, and I ended up doing a cover about recycling. From that, I started to get other gigs with magazines and realized there was an art world, but it was much more limited, at least in terms of audience. If you got your work in a gallery, a few people would see it. But if it was in a major magazine, it could be 200,000, and I found that appealing.

CULTURED: What urged you to document the art being made?

Garner: I was drafted out of Art Center College of Design and flown around Vietnam to be a combat artist. I sketched and took pictures for a year. It’s very bureaucratic, and I don’t know what happened, but we had an interesting setup. Later, the combat artist and I were sent to Hawaii to do the finished work for the army team, but when we tried to get them into a gallery, there was so much anti-Vietnam activity that many refused to show our work.

I thought it was offensive because we were not promoting the war; we were just commenting on it. And so I did something crazy. I wrote a letter to the local newspaper in Honolulu complaining about the treatment that the combat artist had gotten. While putting it in the mail slot, I thought that was the end of it. In the morning, I woke up, and it was on the front page. We got all this attention and it turned around and became an asset. I was also given an army commendation medal for writing that letter. Much later, I became ill from my exposure to Agent Orange in Vietnam, and that’s what’s taking my life now. I feel wiped out, most of my vision is faltering and it’s made everything difficult.

CULTURED: Have the changes in your body resulted in you tapping into other parts of yourself to make art?

Garner: I haven’t been able to draw for about 10 years. My interest evolved from drawings into t-shirts and their interesting history. The white t-shirt became popular in the James Dean era in the '50s, which some advertising individual noticed. "So let’s get them to put logos on their shirts to advertise different kinds of stuff." Everybody had Nike or something on it, and it was an interesting thing because they were not only giving companies free advertising but also paying them to do it.

I found that rather unique as a place where people could display images, so I started making ones with simple captions and no images. Then, as my vision declined further, I used eBay as a way of rummaging through everybody’s closet in America to find shirts with weird or obscure images to collage them onto mine. I liked the idea, and it was enjoyable, but I didn’t expect any attention from it until they suddenly became iconic. This is one thing that I can still continue and at this point I want to keep that going as long as possible.

CULTURED: Was there a moment where you thought about leaving your practice behind?

Garner: No, I never did.

CULTURED: What advice would you give to a young artist that looks up to you?

Garner: I tried to set up an example that nobody else can follow.

CULTURED: Is there a piece of advice you got as a young artist that you’ll never forget?

Garner: I think it’s more of a message from the culture at large: the whole beginnings of consumerism. I guess the word "consumerism" guided a lot of things I did. I just liked the way that things got cycled through and then discarded, the idea that things got obsolete so quickly, and I felt sorry for them. It’s like I never outgrew my childhood notion of wanting to bring things to life, with my backwards cars and collaged t-shirts.

CULTURED: Is there something that felt very important to you when you were young as an artist that seems to be lost in the art world today?

Garner: I haven't been able to keep up with what’s been happening in art now, but it seems like there's a somber quality to a lot of work. There [are] probably some amazing things going on that I’m not aware of, but I think some of the humor and absurdity might be missing. But when you think about it, some of the great absurdists like Marcel Duchamp and his urinal in 1913 and all the stuff they did, all those things about getting commissions from rich patrons and then going out, turning the camera on, and throwing it up in the air and catching it—I feel like I’m maybe part of that tradition.

This interview is part of a series of conversations with female artists over the age of 75. To read more, take a look at our stories with Brazilian sculptor Sonia Gomes, pioneering video artist Dara Birnbaum, and prolific creative Liliana Porter.

in your life?

in your life?