Occupied City, the latest opus from British director Steve McQueen, asks audiences to remember Amsterdam’s darkest hour—its five-year-long occupation by Nazi forces and the ensuing decimation of its Jewish, Roma, and Sinti populations—in the present tense.

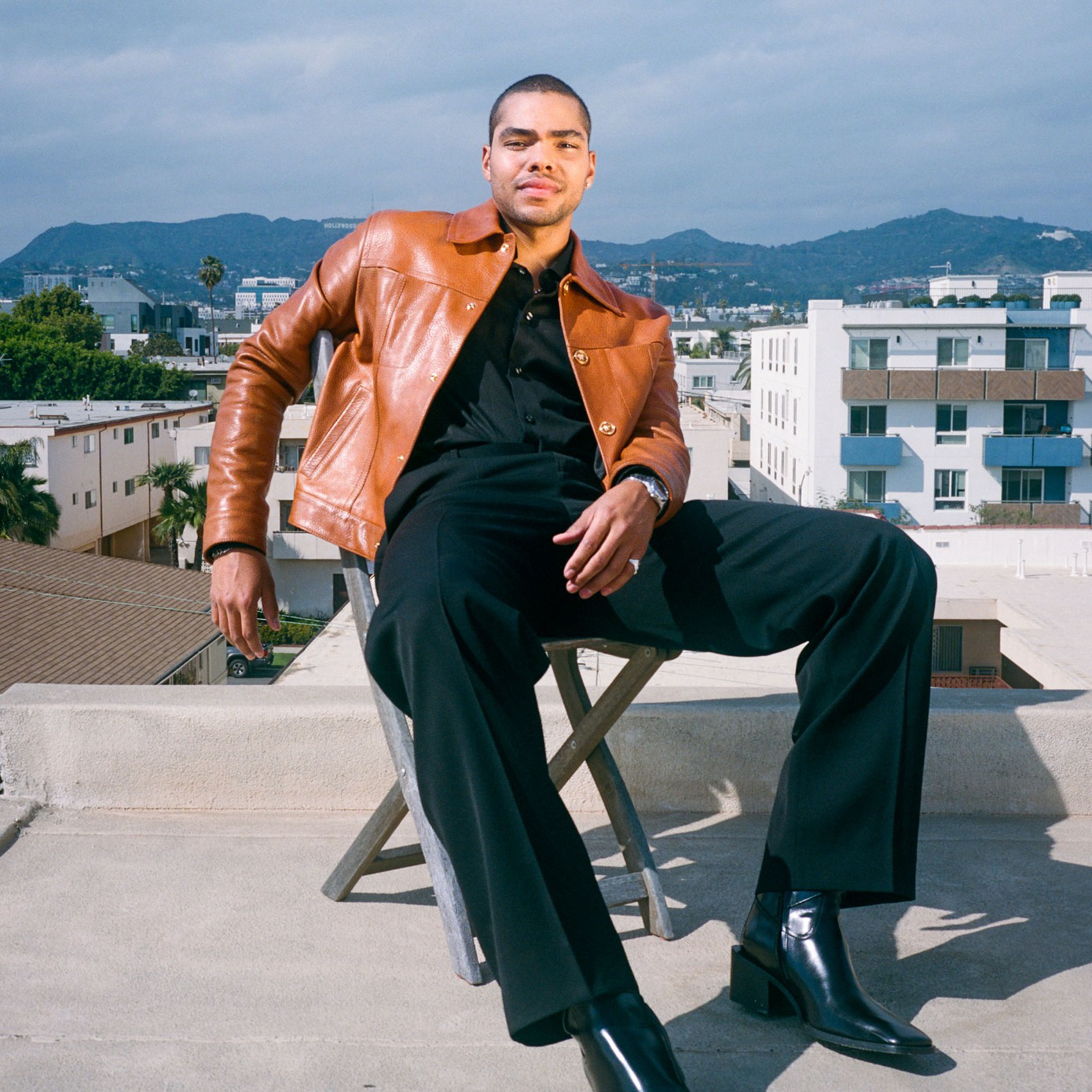

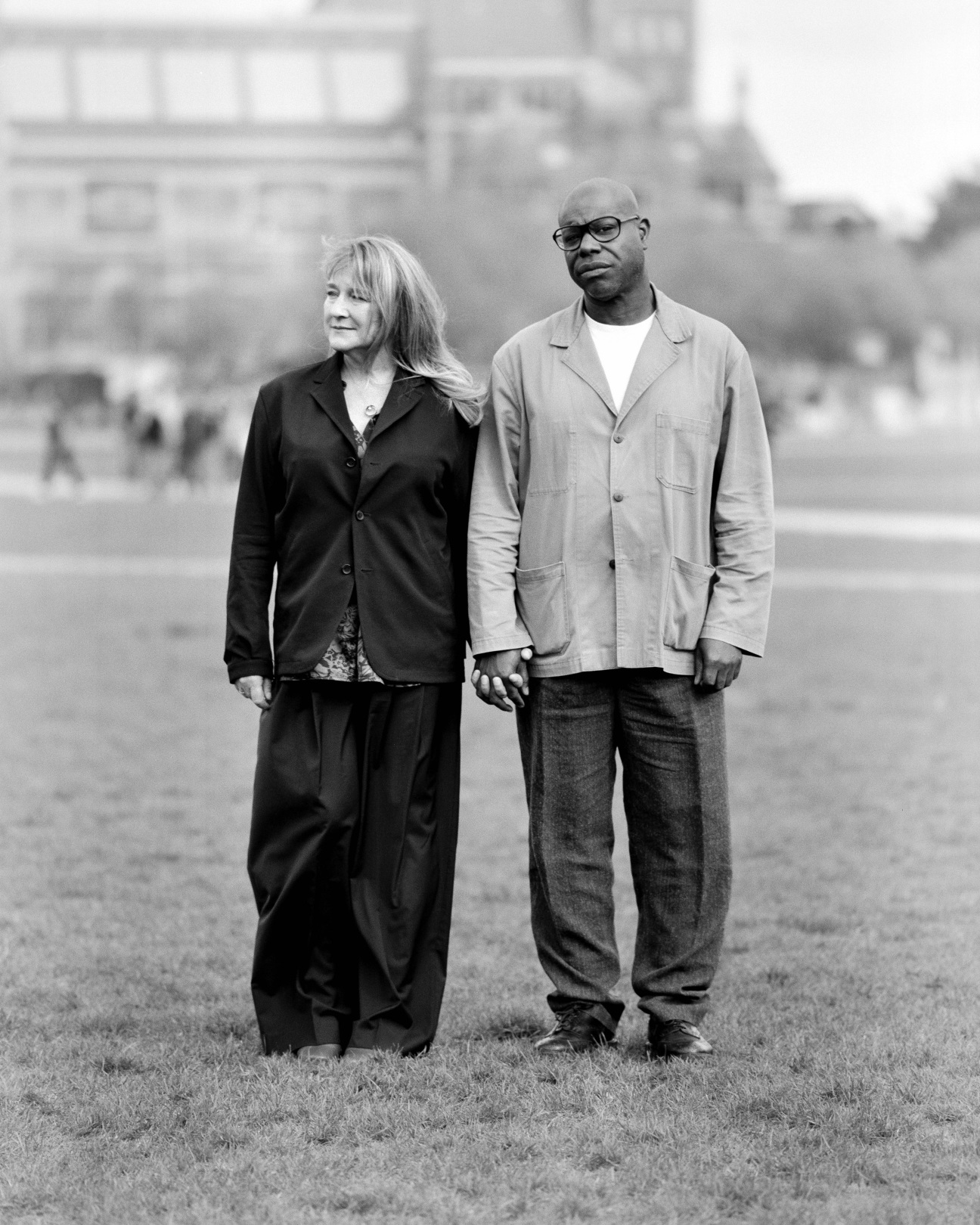

In his acclaimed new documentary, releasing in theaters on Christmas Day, McQueen follows a street-by-street, door-to-door journey of his adopted home, unearthing its devastating reality during the Second World War. Captured between 2020 and 2023 and accompanied by adapted narration from Dutch historian and filmmaker Bianca Stigter’s 2019 tome Atlas of an Occupied City, the 262-minute epic bears witness to the horrors of prolonged violence, and warns against the resurgence of extremism. Here, McQueen and Stigter—creative and life partners—unravel the story behind the documentary.

Bianca Stigter: [The occupation] was always in the background when I was growing up in Amsterdam. You felt that everyone knew, “Oh, don’t buy at that shop because they were collaborators.” The strange thing is that Amsterdam is very much a 17th-century city. You cannot see the war there, but when you know what happened in all those houses, it changes your perception of them. Even Anne Frank was hiding in a beautiful canal house.

Steve McQueen: Growing up in London, the war was promoted as our finest hour—you know, “stiff upper lip,” “keep calm, carry on,” all those things. It was seen as a victory, and all the other stuff was swept underneath the carpet.

I mean, the reason I’m here today is because my parents were called over from the West Indies to rebuild Britain after the Blitz. So in some ways it’s part of my existence. Similar to the pandemic, I feel that there was a silent trauma going on, but it was eclipsed by this victory. That’s the British psyche—there’s so much damage done, but you always put up a front... [When I moved to Amsterdam], it made me think about Britain and how the war was perceived there.

Stigter: I started to work on this period when I was studying history—first, with a focus on monuments and how the war was remembered. There are quite a lot of monuments in Amsterdam, but it’s not in the active memory of the people. So I wanted to make a kind of guidebook or time machine where you could access that period. When people in Amsterdam see the book, they always say, “Is my house in there?”

McQueen: You can think of Anne Frank as a front for the Second World War in the Netherlands because that’s promoted very vigorously. Other things are not, [like the fact that] out of the 100,000 Jewish people who were taken away, 60,000 or more never came back. That’s the biggest number in Western Europe. Like in the U.K., there’s a lot of things that are brushed underneath the carpet. I understand in a way—you have to put one foot in front of the other to go on. But it’s very important that we understand that what we’re looking at right now is a reflection of what happened not so long ago. What the film does is bring that into the present. The whole idea is to make these people human and not just a number or a statistic.

Stigter: I think that partly addresses why the book is so thick and the film is so long. The most haunting part for me [in writing the book] was if I could not tell a story about people because there was so little known about them. You knew they were born, they lived here, they were murdered. That’s a very difficult feeling because sometimes when you’re doing work as a historian you feel like, At least I can make it so that it’s not forgotten.

McQueen: And we didn’t have to go to some far-off country to do it, it’s right on our doorstep. [As an artist] you should be able to make work about the things which are underneath your bed, and that’s what we’ve done ... When I was first thinking about making this film, your book wasn’t in my psyche. I thought, What happens if I get this old footage, and I shoot new footage? I could actually match one top of the other. In the same frame, the living and the dead—I thought that could be amazing.

Then, you were writing the book, and I was like, “Wow, the text is the past, and the image is the present.” We were living in the same house, having two different thoughts on the same thing. It’s almost like [the Beatles’s] “A Day in the Life.” John goes, “I read the news today, oh boy.” And Paul’s in another room going, “Woke up, fell out of bed / Dragged a comb across my head.” And it’s like, “Hey, why don’t we put those things together?”

Stigter: And we had a great team.

McQueen: Extraordinary. We worked together for three years. We were high on this project. All of us were Amsterdamers, and I imagine we were high on it because we saw places we knew with new eyes ... We shot on 35 mm, which was very important because it’s the ritual of making film with five-minute rolls. It was one of the best experiences of my life as far as making work, and of course that’s because I was doing it with my wife. Who knew?

Stigter: When you’re living in the same house, you tend to cross each all other the time.