Over the last two decades, Anj Smith has mined the tangled veins of ecological decay and the gendered form to spawn seething, ethereal paintings that flicker somewhere between portraiture and landscape. The Kent, U.K.-born artist’s practice is characterized by a refusal to speed up, allowing her to add one gossamer layer of meaning after another to her cryptic, densely packed works.

As a result, Smith’s paintings unfurl cunningly—revealing themselves to the viewer who pauses long enough to drink them in. This month, a new series of the artist’s works are on view in “Drifting Habitations” at Hauser & Wirth’s 22nd Street location in New York. Ahead of the show’s opening, Smith visited the studio of her friend, Erdem Moralıoğlu, whose eponymous womenswear line reflects a similar reverence for history, memory, and inscrutability.

Erdem Moralioğlu: Anj, whenever I see a work of yours, I have an immediate desire to untie it. There are so many secrets hidden in the corners and layers of each piece. I was intrigued by something in the exhibition catalog for your upcoming show. You speak with Dr. Orna Guralnik—a specialist in the transmission of trauma—about the idea that trauma can be inherited. How do her studies of the human mind connect to your work?

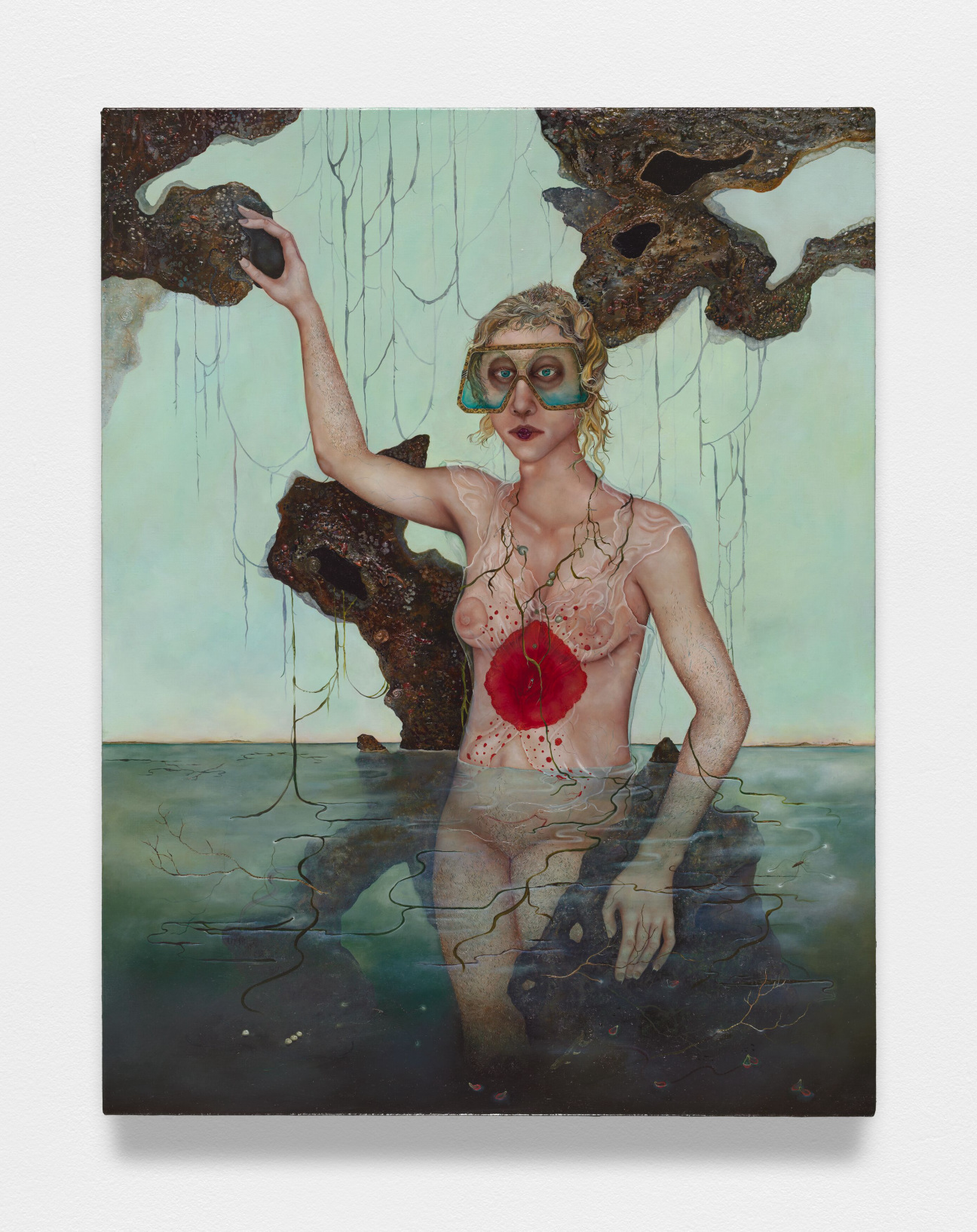

Anj Smith: With the new series of nudes that I’m about to show, I’m exploring what it’s like to inhabit a female body in a way that is not definable, linear, or easily gettable, but rather presents a self in flux, with all these historical gazes or idealizations laid upon it. Dr. Orna was very helpful in showing me that we can be 100 different people a day. She gave me the language to express that.

Moralioğlu: You discuss the tension between anxiety and the erotic. These are seemingly opposing forces—the erotic is something that draws you out, anxiety turns you inward. How do you relate to that push and pull?

Smith: I’m painting in a way that I hope produces that push and pull in a viewer. There are things that draw you in—a luscious palette, impasto or glossiness—but there’s also a refusal at play. One thing I’m always trying to work out is, How do I point to the most important moment in a work to the viewer? The same may be true for you, Erdem. There is so much detail in your garments—embroidery embedded under tulle, lots of diaphanous layers. How do you expect people to encounter and read your clothes?

Moralioğlu: There are different phases to a body of work. You have a show, which is like a manifesto to introduce your concept. It’s almost like creating a film—the lighting, the sound, the earrings, the shoes, the movement, and the makeup come together to embody what you’re trying to say for the season. Then there’s the phase where that dress hangs in a store, and gets absorbed into someone’s life who you don’t know, and who doesn’t necessarily know that the dress is inspired by a Victorian “House of Hope” from 1860, or by Deborah [Cavendish, duchess of] Devonshire. But back to you, Anj. The writer Claire-Louise Bennett has contributed to the exhibition catalog—The New Yorker has described her work as a “war against narrative.” Does that resonate with you?

Smith: Absolutely. History has been presented to us in this linear way by a very specific group of people. If you’re on the outside of that group, as I feel I am, you learn to communicate in a more oblique way. I made a painting for this show called But Tell it Slant [2023], which is a reference to an Emily Dickinson poem. If you’re going to tell the truth, she advises, do it incrementally, gradually. My work has been called surreal, but for me, it’s not surreal. It’s just not linear. I also chafe a bit at the term because the surrealists didn’t accept women, so it feels like clumsy terminology.

Moralioğlu: I struggle with it too. Dalí is so uninteresting to me. But Bosch, I love. That’s surrealism to me. I do want to ask about your female nudes, the ones standing in the water. One of them is But Tell it Slant, and the other is Rosemarinus [2023].

Smith: It’s funny, I had a studio visitor many years ago, and he was physically repulsed by all the hair on my figures. He goes, “Why are they so hairy?” I was mortified because they were clearly self-portraits. I’m still slightly traumatized. Anyway, these paintings are an exploration of that. I love that they’re both standing in water, this mysterious element without any set contours. These paintings are about having a kernel of agency, being able to foster hope and creativity in the midst of all of this current murk.

Moralioğlu: When you begin a work, are you mapping out an equation that you already know the answer to, or is painting a process of exploration?

Smith: I do understand the answer before I start. I’m always really mindful that people spend a nanosecond looking at painting. I’m trying, on one level, to create a work that’s legible to the viewer who stops by for one second. But beyond that, I’m trying to invite the viewer to slow down. The paintings are quite aggressive in that way; they require time to unlock. Small details will emerge slowly, and things become legible after minutes. In our throwaway culture, everything is disposable and cheapened. What I’m doing is quite countercultural—it’s a slow burn that rewards and nourishes you over an extended period.

Moralioğlu: I feel like you’re describing the work Intermittence [2022]. It’s a blackened sky with a singular, elasticated lightning bolt. It’s distinct from the rest of the paintings in the show.

Smith: The title comes from Dante. I was reading the Inferno, as one does for a bit of light relief. There’s a tier in Dante’s vision of hell that is complete murkiness; the only light sources are these blinking fireflies. I love this idea of flickering possibility in our dark moment. There is also an ambiguity at the heart of the piece: Initially, it feels quite celebratory. It could be a firework. But if you spend some time with it, you’ll see a few spent flare canisters in the foreground. The assumption could be made that this is a distress flare. It’s a response to living in our conflicted time.

Moralioğlu: I’m fascinated by your ability to weave these dialogues and histories into your work.

Smith: I’m not one of these artists who feels you can ignore the past. I see that in your relation to the history of fashion and textiles. I love your jacquards—a textile that, originally, existed to make sumptuous brocades and damasks more accessible for people. You’re making this historically loaded textile relevant in a new time.

Moralioğlu: I’ve always been fascinated by history. I love using a silhouette or a textile technique from the 1920s or 1860s to shapeshift or travel in time. It’s that layering, all those little tangents that come together to tell a story.

“Drifting Habitations” is on view through January 13, 2024 at Hauser & Wirth’s 22nd Street location in New York.