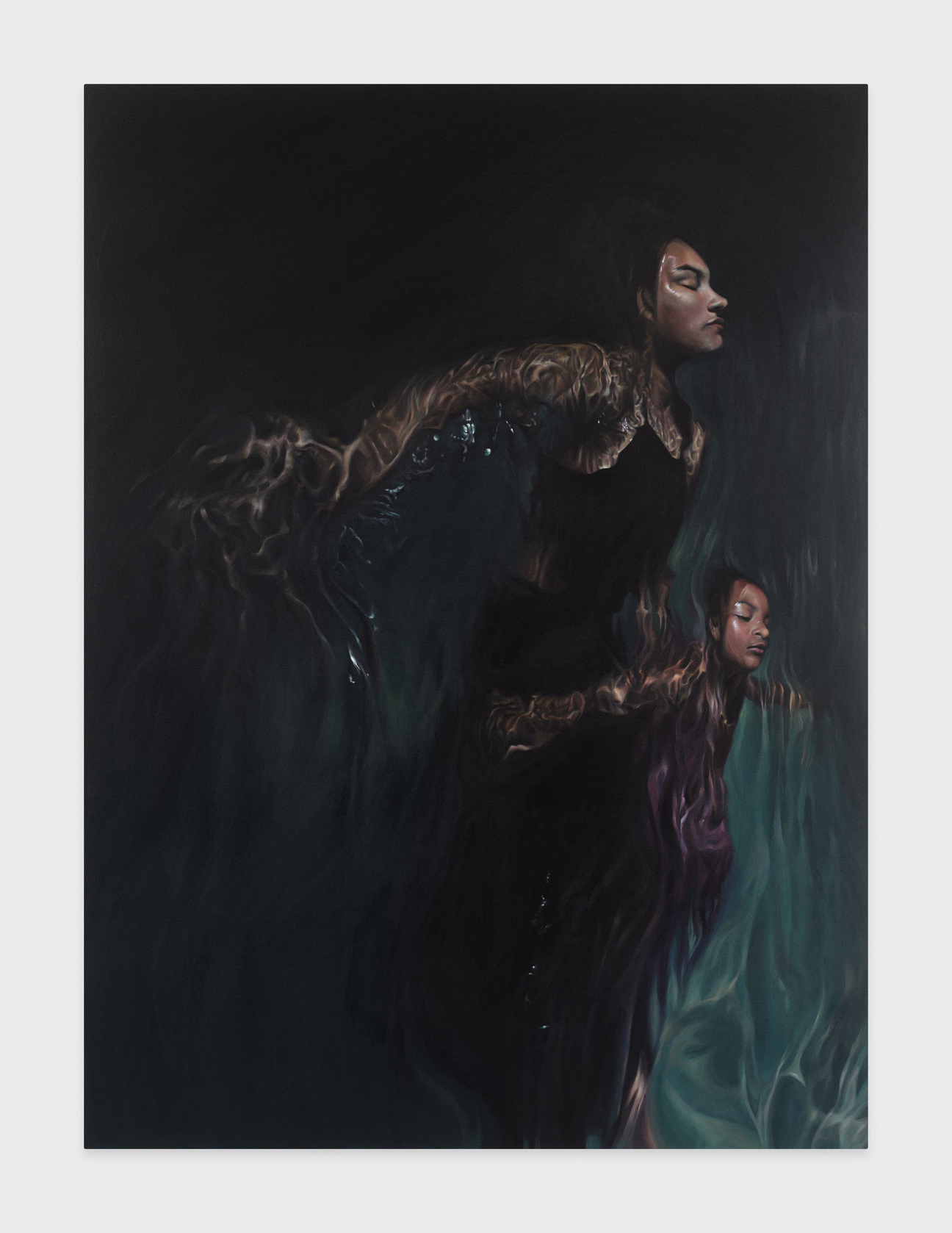

When Calida Rawles first turned to water, it was as a means of obfuscation. In her sprawling, eerily hyper-realistic paintings, Black women and children drift peacefully across the surface of water as if transported elsewhere, or submerge themselves into its crystalline depths to escape the eye. For Rawles, situating her subjects’ own bodies within bodies of water sparks a plurality of meanings—moments of catharsis and healing, or of confrontation and resistance.

Recently, however, Rawles’s water has transcended its role as a placid membrane between viewer and subject to become a weathervane—a reflection of the turbulence in the world outside of the work. “Most of these works—not all—have darker water that my figures are submerged in,” says the artist of her latest series of monumental paintings—her largest to date. “It's me feeling overwhelmed and unsure of what's happening in today's world.” This fall, the series is on view as part of “A Certain Oblivion,” Rawles’s debut New York solo exhibition with Lehmann Maupin.

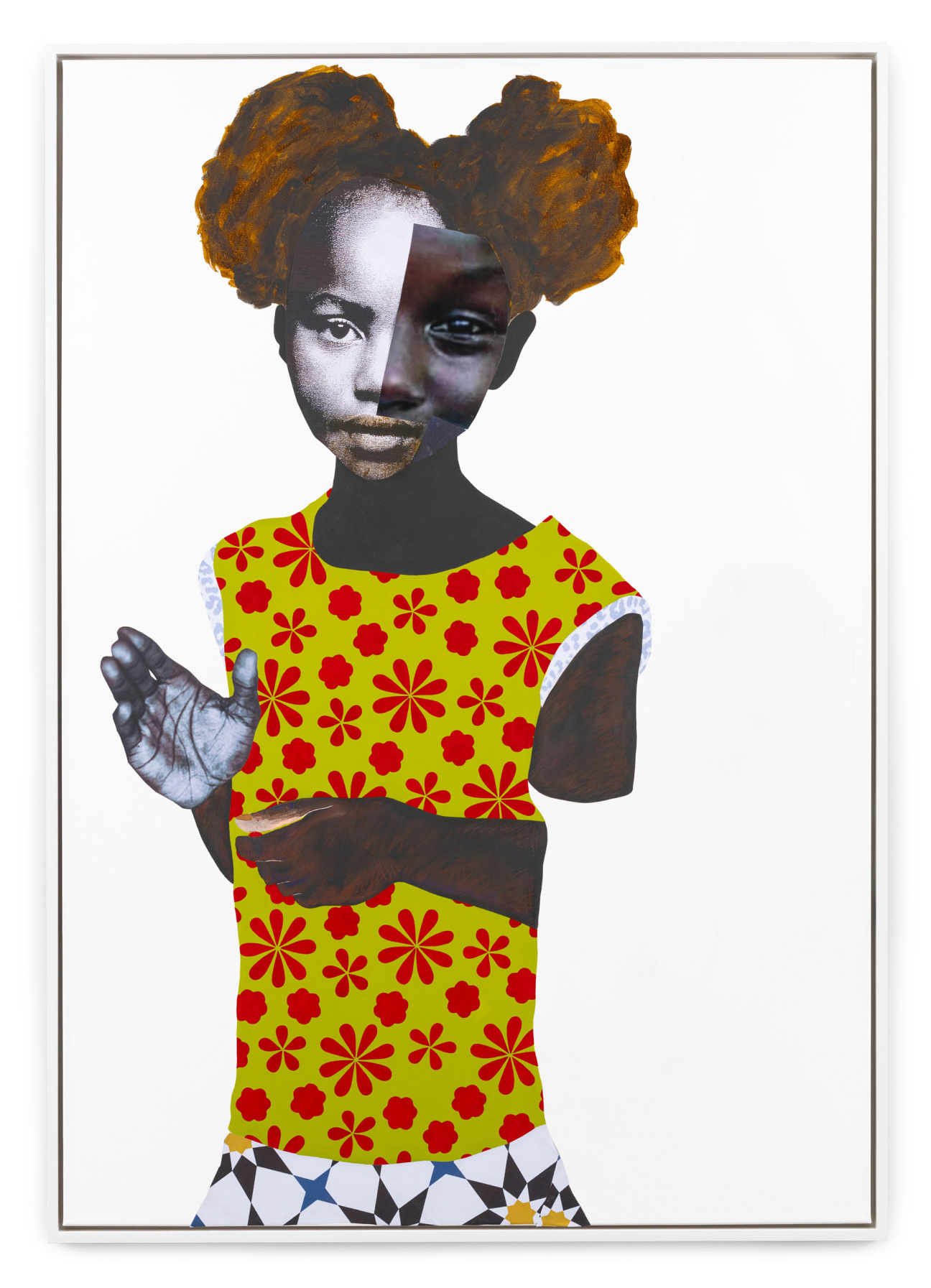

To mark the occasion, Rawles sat down with mixed media artist Deborah Roberts, whose show, “What about us?” opened earlier this week at Stephen Friedman Gallery. With her first New York solo presentation in over five years, Roberts unveils her most ambitious collage works yet, a continuation of her inquiry into Black childhood that emphasizes physical gesture—a hand reaching toward the viewer, an arm raised over a subject’s eyes—to evoke a feeling of direct address or self-protection.

Like her Los Angeles-based peer, the Austin-based artist is showing some of her biggest works to date at Stephen Friedman, a mammoth undertaking that—for both artists—is as invigorating as it is exhausting. Here, Rawles and Roberts discuss the hidden benefits of painting on a deadline, carving out time for self-care, and making work that responds to the worlds trials and tribulations.

Deborah Roberts: Rawles, I knew your work before I knew you, because you designed the cover of Ta-Nehisi Coates's book. We have a mutual friend in Amy Sherald. I finally met you at my reception two years ago.

Calida Rawles: I had the same thing. I remember you had a show years ago, with all these names, these common Black names that were misspelled but are common, like Keisha. I was blown away by the concept, I had never thought of how these names that are common in my community are “foreign” to our [larger] culture. I thought it was brilliant. That was the first time I said, “Who is that?”

It's been a blessing to see your work grow and I'm so happy that the art world has caught up with you, and has recognized what you're doing. I'm very excited that we're both doing these November openings in New York. I wish I could have been [at your opening]. I was preparing for my own that's coming right behind it!

Roberts: It's overwhelming. I was talking to Amy, who was so happy that we didn't schedule our two openings and dinners on the same night. I’m excited to come to yours. Having a fall show in New York is exciting in its own right. This is not your first show, right?

Rawles: This is the first big, big solo show.

Roberts: Get ready, it's a lot. All the smiles, all the photos, all that. I saw it happen to Marilyn Minter, and thought, Okay, that’s not going to be me. There are so many people who really just want to wish you well and share the love, but it's overwhelming. Are you very excited about the work? What's the theme of your show?

Rawles: The title of the show is “A Certain Oblivion.” Most of the work, not all of it, has darker water that my figures are submerged in. It's me feeling overwhelmed and unsure of what's happening in today's world. Yet they still have agency, strength, and power throughout. That's what I'm always trying to convey.

The water is symbolic to me, it's something that is dangerous, scary, overwhelming, and larger than us. At the same time, it feels good and refreshing. I use that positivity as an undercurrent in the show. I'm excited to see where I pushed the work in a new direction for people. I hope it will be received well, but even if not, it will be well received by me.

Roberts: People are intelligent, they will understand. Our first nine months of existence are in water. We are the most vulnerable in water. Next week when all the chaos is over, I'm going to California to seek the water, the calmness of the water. I think your play on dark and light makes sense—we are in dark times. It's very anxious out there, and expressing that may lend itself to lots of conversations—and hugs—that we need to have right now.

Rawles: I appreciate you talking all about me and my water. Now tell me about your show!

Roberts: My stuff is different this time. I wanted to push the idea of collage and find out what my stopping point was. I did that. The show is called “What about us?” I chose to couch my argument in the subject matter of children, to see how a little kid navigates the trials of adulthood. All the problems that we have as women—how we’re treated, our efforts to exist and to be beautiful, our hair—when do we put on our gloves and fight for our own identity?

Some of the work speaks to what happened to Ralph Yarl when he walked up to that door and was instantly shot. There is also the notion of bringing people into the work—and keeping them out—with physical gestures. It was about protection and acceptance in that way. I was really happy with all the works but one. I think it's ugly.

Rawles: Stop! I already know it's not ugly. No, no, no, I'm not gonna let you diss your child with me around. That is your baby. Maybe you need more time away from it to appreciate it.

Roberts: And I got an ugly baby. [Laughs] No, all babies are beautiful. I accept that interpretation because as Black artists right now, we're at the top of the game. That means there’s a lot of pressure—from the galleries and institutions—to get more work out. We don't get to sit with it long enough because everything is so hot and people are after it. But you work slower, right? How many works do you have in this show?

Rawles: I do need time. There are 10 works in this show. Recently, I see that I'm moving faster, which is good and bad. Bad because I wish I had more time with them, good because I'm happy to push myself as a painter. Sometimes I get all caught up with my little brush, pushing my paint, when it isn’t necessary. It has become a fun exercise because now some of the work is more painterly.

Even though someone else might say, “It looks just like a photo,” I don't see that. I see all the play, the pieces that I pushed further than you'd think. I do wish there was more time, but it is beautiful to be wanted like this, right? When no one wants the work, you’ve got all the time in the world.

Roberts: I know, and I've been there. It's so amazing how our lives have changed in these last few years, just because the art world finally took a look at what we’ve been doing and saying. This is our moment. We can have all the time in the world and be worried about our light bill instead. But you still need to make time for that self-care.

Rawles: I have to do better at that. I got a Peloton, is that self-care? I run myself to death, so I don't paint myself to death.

"A Certain Oblivion" by Calida Rawles is on view through Dec. 16, 2023 at Lehmann Maupin in New York. "What about us?" by Deborah Roberts is on view through Dec. 22, 2023 at Stephen Friedman Gallery in New York.

in your life?

in your life?