Some musicians like to put a healthy distance between themselves and their audience, whether through songwriting steeped in obfuscation or a suite of burly security guards lining the perimeter of the stage. It’s one way of managing the relentless demands of the business. But Devendra Banhart isn’t one of those artists.

Since the beginning of his two decade-long career, the "freak folk" musician has made a point of baring it all on his records, dropping tracks like an anvil and unburdening himself of their emotional weight. On his latest album, Flying Wig, out last Friday, the tradition continues.

Over the past few months, Banhart has been burning his notebooks, which include diary entries that date back to his teen years. For the artist, it’s just another exercise in letting go, an impulse that drives his artistry and often his lifestyle. As he puts it, “Impermanence is part of the gig.”

To mark his album release, the singer connected with CULTURED to reminisce about his time spent writing poetry in the woods with Flying Wig’s producer, fellow musician Cate Le Bon; the Kurt Vonnegut writing advice he holds dear; and why, for him, wearing dresses doesn’t have to be “a thing.”

CULTURED: I listened to this album a few times. I love it. But I also find it very different from a lot of what you've done. I'm curious, how do you put yourself in a new sonic space?

Devendra Banhart: Yes, and no. It's a mysterious thing that ends in one facet of my consciousness. It's such a simple formula. I'm writing about what's happening in my life at that moment, what I find interesting, what I'm seeing, and the vehicle of propulsion that leads me down a particular narrative are a few questions. What am I keeping from myself? What am I terrified of? What am I ashamed of? What do I regret? How can I even express something that's a universal feeling where someone might go, I feel that, but I hadn't heard that that way? The other thing is mysterious—you can pretend like it's not there, but that's a big part of the gig, this mysterious thing. It really starts to work when you get out of the way.

CULTURED: How do you let that mysterious thing come out and walk around?

Banhart: When I was a young gal, I had a lot of bad rituals. Not that I don't have bad rituals to this day, but eventually you develop healthy rituals to help you get out of the way. Knowing that's a big part of it is the beginning. If not, it's just a crazy ego trip. There's some simple architecture there, where it's like, “I'm writing this record…”

I remember reading Kurt Vonnegut saying that, “All writers have just one or two people that they're always writing to. For him, I think it was his sister. That [direct audience] keeps things in a way where you're just so yourself, and it's almost like getting out of the way. One of the [other] ways that you can get out of the way is admitting to yourself that there's a responsibility that comes with following through on this thing that you know is irrational, but it's the most important thing in your life. “Follow your bliss” doesn't mean get fucked up all the time, it means take responsibility for whatever kind of strange gift you've been given … Part of the gig is to go on that journey alone.

CULTURED: I read that the album is about embracing certain lows. I'm curious about the roots of those lows. There's that famous Tolstoy line: “Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way." In some ways, there’s more space for granularity and digging into your own recesses.

Banhart: Those two words, “happy family,” I have no idea what you're talking about. Most of us probably live in a combo of something right in the middle of a happy and unhappy family. In Tibetan Buddhism, there's a prayer where you say, “I'm offering this to all the children whose parents don't love them.” It kills me, just to consider that. We pull a lot from that. It’s why those first records are always so powerful and intimate. We should be kind to people after they are cruel to us because we know how bad it feels to receive that cruelty.

CULTURED: How does it feel to put those low moments on display in this way?

Banhart: From the beginning of my career, it was never an option to not share things. You share it, and you move on.

CULTURED: What you’re describing is an art in and of itself, sharing and moving on.

Banhart: I'm so judgmental. I try to just do the thing and move on. My pantry has no food in it, it was just notebooks from 20 years of albums. My archives. I looked at it today and said, “Wow, this is just dust,” so I decided to burn it. I burned everything. I burned every notebook, starting with ones from when I was 18.

It felt like I was shedding some skin. I did this over a period of months, because, California, fire, you know… In one sense, we do our work, we share it, and we move on to the next thing. We honor the work, but we don’t get too wrapped up in it.

There was a moment where I panicked, and I regretted it. Right then, a scrap of paper floated up from the fire and I grabbed it. I promise this is true. On it I had written, “fruit is cool.” So, yeah. I don’t think much was lost by burning my journals.

CULTURED: What are some of the non-musical inspirations for this album?

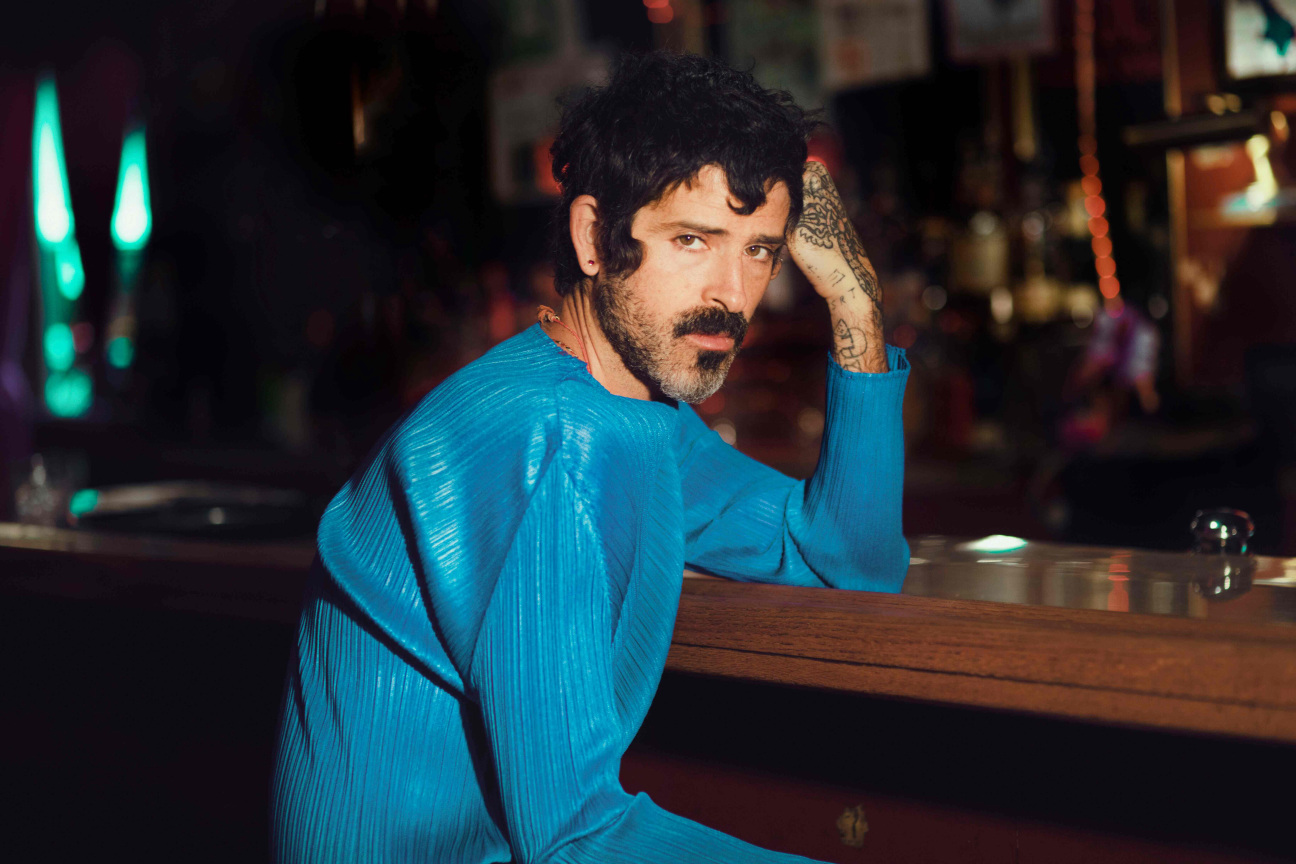

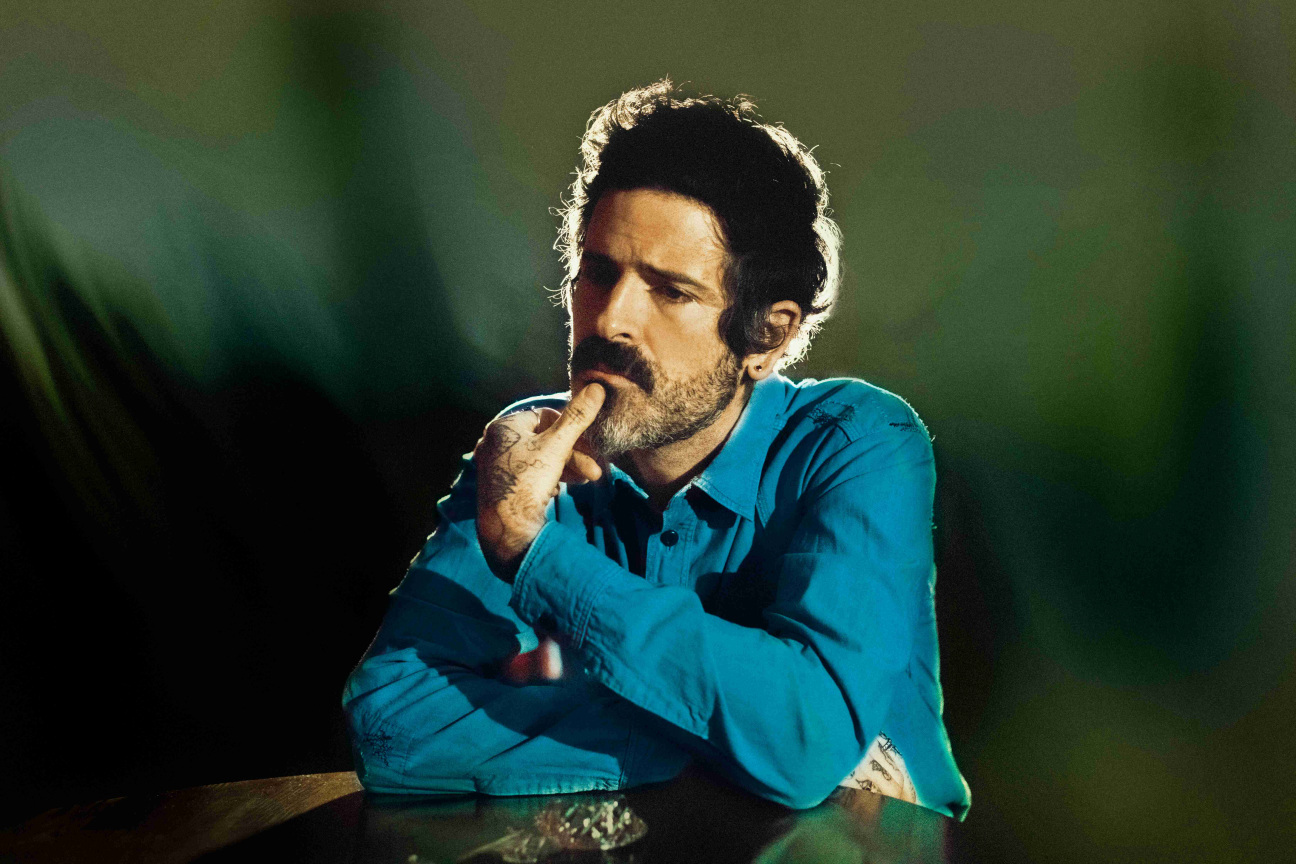

Banhart: The first thing that comes to mind is fashion. I wore this Miyake dress every time we were tracking. It marks the transition from my day to day, and entering my portal of performance, transitioning to the stage. Clothes are ritualistic tools of embodiment, the armor for a ritual. For me it was putting on this Issey Mikaye given to me by Cate le Bon, who produced this album. What you wear shapes the way you feel and think. Sometimes I’ll put on a mini skirt, something I’ve been doing since I was nine years old. I’m a straight man who loves wearing dresses and feels safe, powerful, and beautiful in them.

CULTURED: Is that ritual one that carries over from previous albums?

Banhart: I've always worn dresses, but I never wanted to make it a thing. The last few records, I’ve just been wearing things that make me feel good and comfortable. On this record, there was a real sense of loneliness and longing that carried over from the pandemic. Impermanence is part of the gig; you’re gonna get sick, you’re gonna die. [But] something about the mega impermanence of that time had a different quality. I wasn’t as excited to write music. And yet, it was so critical to write music. I became nihilistic, but I also had this urgency to make my final thing.

The texture of why I’m singing and how I’m singing changed, so I really needed something that felt like a primordial matriarchal energy. It worked out beautifully that Cate gave me this dress, and it was interesting that the dress was Miyake, because their pieces are particularly otherworldly. I felt like I was from a different planet. That was really healthy and healing for me.

CULTURED: What is your relationship like to Cate and has it evolved? What did she bring out of you?

Banhart: It was supposed to be co-produced, but five minutes into recording, I called my manager and said, “Cate's producing.” It was so clear that she was the right choice. She used poetry in this really practical, utilitarian way. Sometimes I’d be crying and she’d say, “What’s wrong?” I would be crying because the music sounded so much like what it sounded like in my head. It felt so amazing to have someone translate something and have it be so close to what I was envisioning. It takes a lot of intuition, but we’ve also been connected for a long time. I really recommend working with Cate, or someone who’s a better singer, songwriting, lyricist, musician, person, by far. If you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em.

CULTURED: Could you elaborate on the idea of this album feeling like a melancholic massage, or weeping in a very nice outfit?

Banhart: We tried to embody that with this mini sci-fi scene. Dorian Wood is an incredible singer, poet, and performance artist. I've known him for years. He was massaging me during the set, and the others were like, “Let’s put some fake tears on Dorian.” He responded, “Would you like me to just generate real ones?” I feel the energy start to shift and then feel his tears start to drip down my back, all while I’m getting massaged. Suddenly, we’ve entered a new stage in our relationship. It was really powerful. I was like a non-dualistic consciousness; I don’t exist, but I’m alive. I’ve had many states of altered consciousness, but never one born from a friend. This thing, weeping while getting a massage, was helping us figure out how to describe the record. The feeling of being alone together. To me, that feeling is one of the most comforting places to be.

in your life?

in your life?