Most artists use paint, plaster, or canvas. Montreal-based artist and filmmaker Caroline Monnet's tools of choice are insulation, plexiglass, and mold. Monnet grew up lending a helping hand to her parents, who flipped houses. When she ventured into the visual arts after a career in filmmaking (one that saw debuts at the Toronto International Film Festival and Sundance, among other festivals), the self-taught artist picked up familiar materials she knew how to manipulate. Her interest in the tools of construction blossomed with a 2021 solo show at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, but with her first U.S. solo exhibition, “WORKSITE” at New York’s Arsenal Contemporary, Monnet moves past the exploration of home and into the tricky matter of building cities. Here, the artist delves into her myriad inspirations and her work’s relationship with her Indigenous Canadian roots.

CULTURED: How did the Arsenal Contemporary show get put into motion?

Caroline Monnet: It's been an ongoing discussion with Anaïs Castro, the current director of Arsenal. The show was supposed to be last September but it got delayed because with Covid, everything got pushed down. We decided to do it one year later, which is actually really great, because I feel the practice has really evolved.

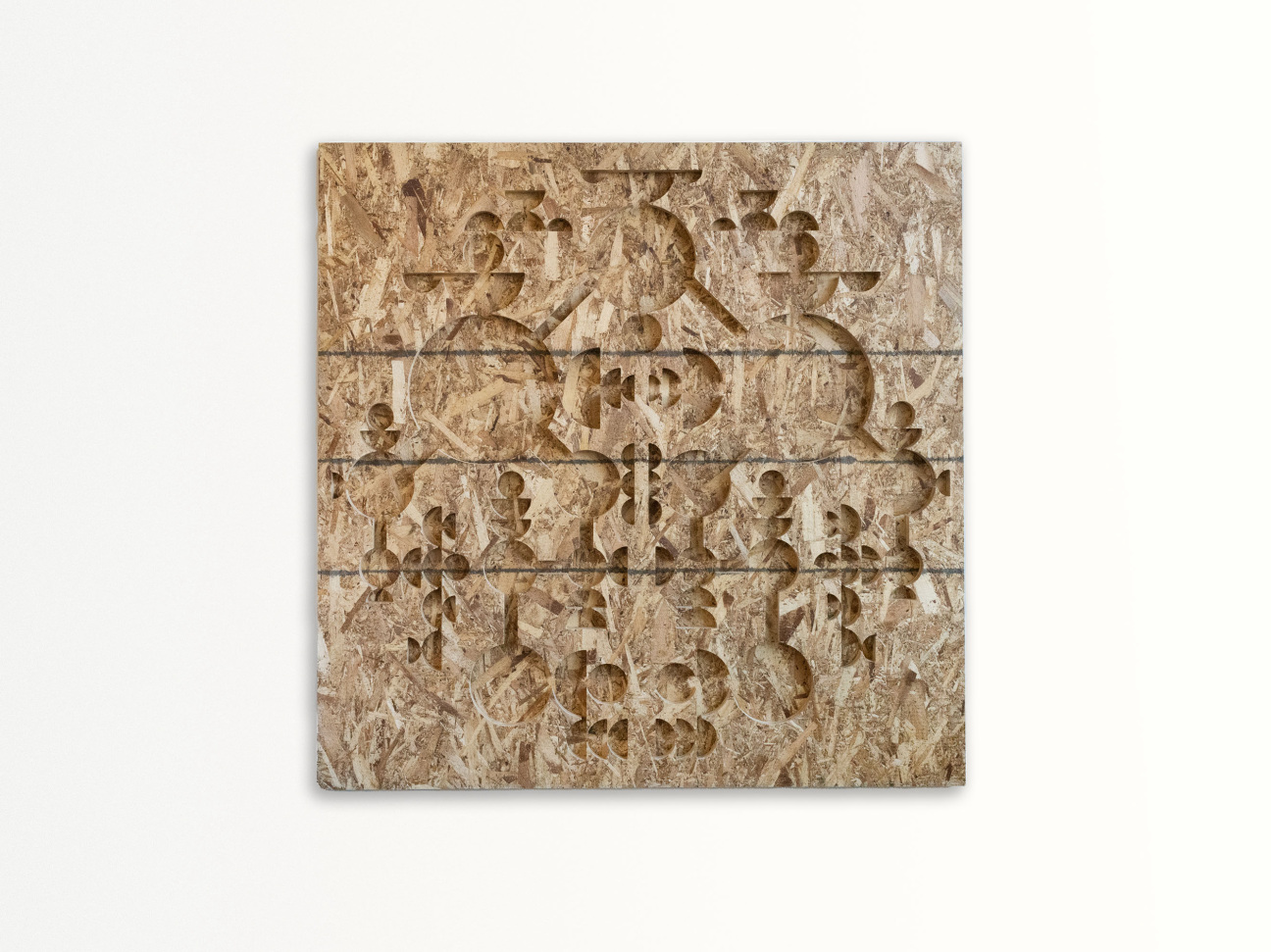

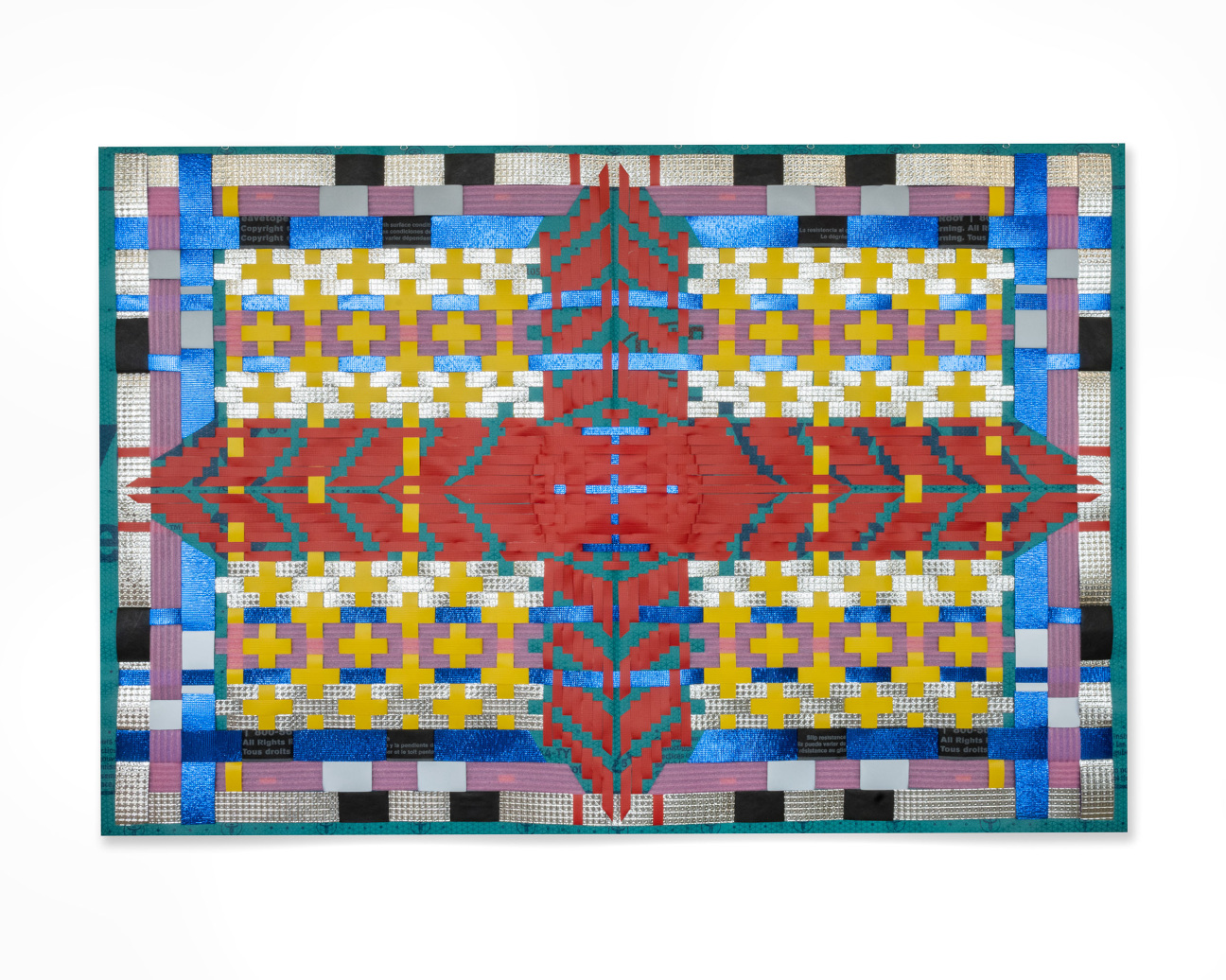

For the past couple of years, I've been working a lot with construction and building materials: doing embroidery on water or air barrier membranes, cutting into Styrofoam, or anything that you would use to build a house. I experiment with these materials and alter them into very poetic artworks. The past couple months, I've been really into architecture and cityscapes. I went from the idea of a home into how we build cities.

CULTURED: Your parents flipped houses. Having helped them with that, do you think this interest in building materials is something you inherited from them?

Monnet: I didn't realize growing up that would have such an influence on my practice. I studied sociology and communication, so I was always interested in social backgrounds in terms of history, politics, and geography. But when I started looking at habitat, and how we shape our environments, and how environments in return influence everything that we are, I started experimenting with building materials and realized it's kind of a comfort zone. I've been working with these materials since I was a kid. I would come back from school and put insulation into walls and help drill some Gyproc.

CULTURED: The Arsenal show was inspired by New York’s history and involvement in the timber trade. Do you have a personal connection to New York, or do you always adapt your exhibitions to the spaces they are in?

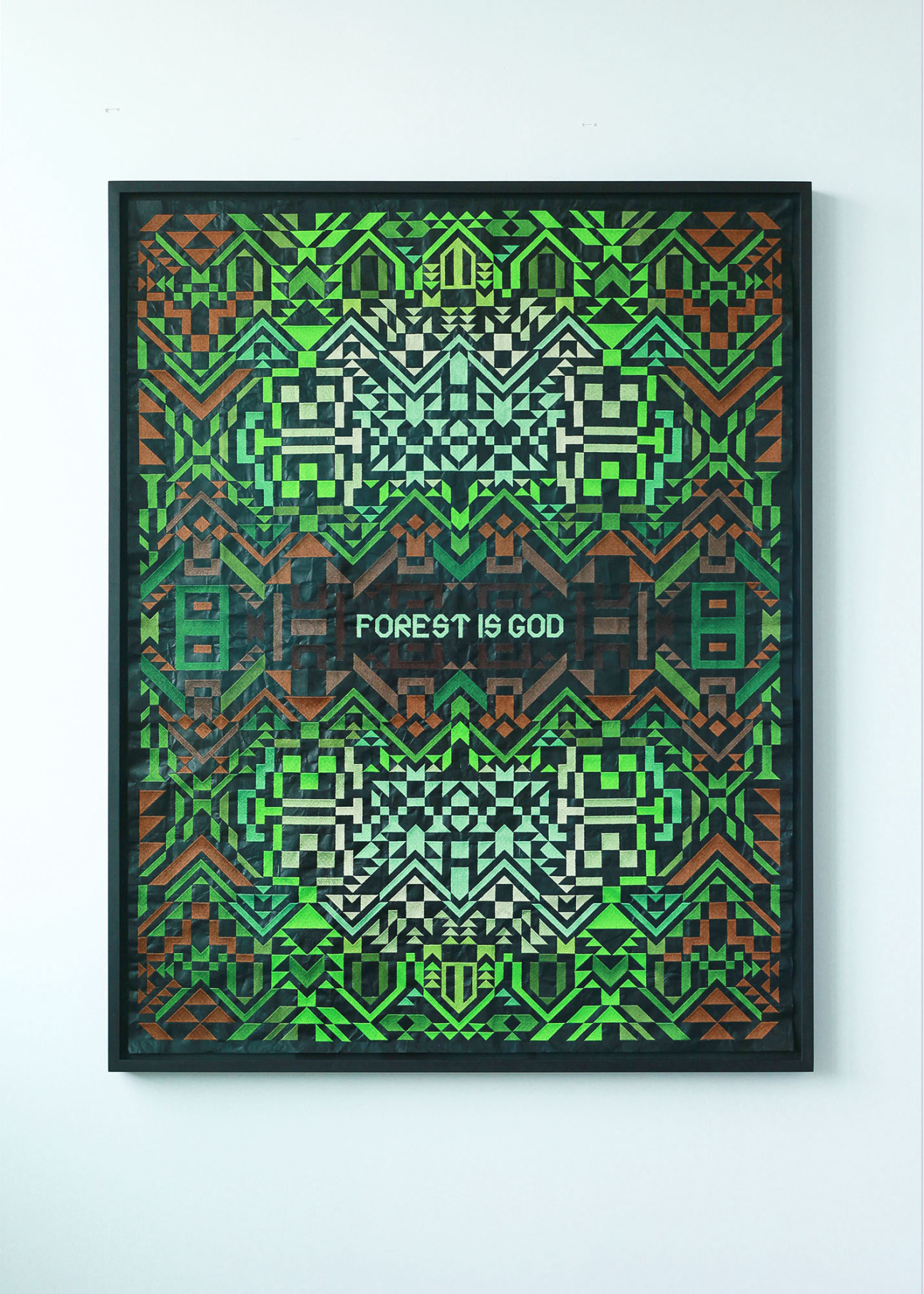

Monnet: I always like to place the artworks in relation to where they are going to be exhibited. I knew I wanted to work with the idea of a “worksite” so I did a lot of research around construction sites. The word “worksite” comes from the French-Canadian word “chantier.” Back in the old days, or even my grandfather's generation, it's a place men would be sent to cut down trees to sell them, and also to make room to build buildings and make villages, and after that, cities. I thought it was so interesting to think about how cities as big as New York were made on the backs of trees; that nature and economic development are intimately linked.

Looking at the history of New York, I found out that before New York City [was established] there was a forest that is considered the oldest old growth forest in the world. It's so interesting that people were sent to Manhattan to cut down trees to create some kind of economic hub and build these buildings. And those trees ended up inside buildings. Everything is linked.

CULTURED: Your work has a throughline in disrupting narratives or histories around Indigenous communities. What do you hope people might take away from this exhibition?

Monnet: I embed a lot of Indigenous iconography in my work, especially through design. I embed a lot of traditional designs into the building materials themselves. Those designs are inspired by traditional Anishinaabe design—I'm Anishinaabe by my mom. I like to see any surface as a potential for ornament, where we can instill pride and Indigenous presence back into our cityscapes.

The designs that I make, they're inspired by the tradition, but I make them on the computer. So they're really machine-made and industrial. And they look very futuristic, because they start looking like QR codes or city mapping. And that's where I'm interested. What's the continuation? What's the legacy that we can carry into the future? I'm hoping that this practice will evolve into exploring the solutions for better, eco-friendly ways of building because we're seeing how cities have their own defaults.

CULTURED: Have you found these issues that you're talking about—whether they are within Indigenous communities or eco-friendly city planning—to be pretty comparable between the U.S. and Canada?

Monnet: I think the U.S. is slowly starting to catch up on Indigenous issues and realities. We're not so different in Canada [from the] the U.S., in terms of what happens to Indigenous communities and our relationship with the country. The exhibition is also about reminding ourselves that the environment is important. And that's very true to Indigenous philosophies. Everything is interconnected: if there's sickness, like a pandemic for example, or if we cut down trees, the quality of air goes down. I grew up with this knowledge from a very young age. This show is about trying to remind people that economic growth depends on our resources and how we treat the Earth. How can we rebalance that relationship? And that doesn't change whether you're in Canada or the U.S. Or anywhere in the world, as a matter of fact.

"WORKSITE" will be on view from September 8 through October 21, 2023 at Arsenal Contemporary in New York.

in your life?

in your life?