This is Turning Points, CULTURED’s column dedicated to big life choices, bucket-list moments, career shifts, and forks in the road. This week, author Patrick Bringley talks about how working as a guard at the Met changed the way he sees the world.

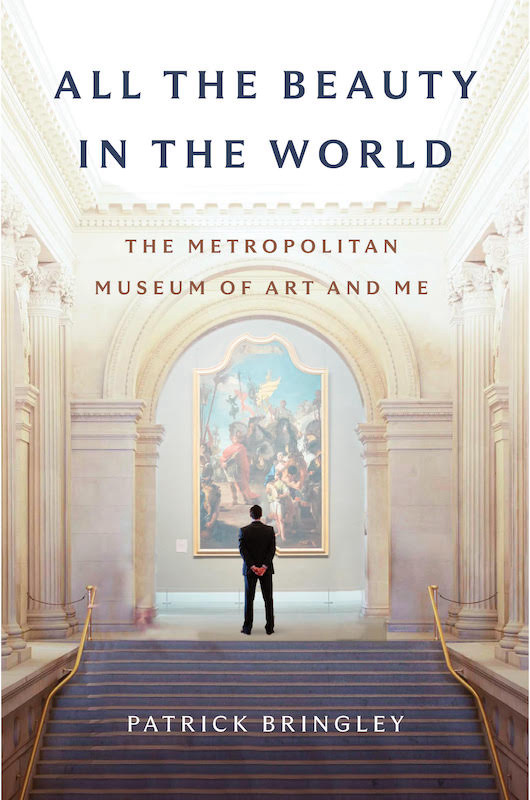

After college, writer Patrick Bringley landed what a lot of people would consider a pretty plum job: a full-time position at the New Yorker. But his life vision changed suddenly when his brother was diagnosed with cancer. After his sibling passed away, Bringley took a job as a security guard at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. In his recently published memoir, All the Beauty in the World, Bringley describes the role as “the most straightforward job I could think of in the most beautiful place I knew.” He tells CULTURED about making the decision to step back well before the Great Resignation, how he found a book agent, and how he’s kept his commitment to himself even after leaving the Met.

“In some ways, my gig at the New Yorker was really good. I felt proud to be at a prestigious magazine. I imagined myself climbing up the ranks. There can be something very alluring—but also very deceiving—about feeling like you're somebody just because you have a fancy business card. But the reality is that I was just 22 years old when I got that job. I didn't have all that much to write about because I hadn't thought too many original thoughts.

Then my brother got sick. And I lost interest in that world and felt the real rubber-meets-the-road aspects of reality. When he died, I didn't relish the idea of going back to an office job. I wanted to do something straightforward, where I was able to think about things that might feel a little more essential.

Art is not really my background, but I thought, I could get a job where I just keep my hands empty and my head up and exist inside this beautiful world. So why don't I try that?

When I went there [in 2008], I very much was expecting to enjoy the aspect of it that is very quiet and very watchful. You put on this suit, you're camouflaged from the world, and you stand in the corner and watch people flow by.

I don't think that I had fully imagined the extent to which the museum is a little world and that there are over 500 security guards, and within that there is this fascinating culture—or, really, many different cultures just within the ‘Guard Corps.’

I was just 25 years old when I started at the Met. Many of my colleagues were twice my age. There is no one straight line that leads people to become a guard, so you get a tremendous diversity of people—not only in backgrounds, but also just in terms of the way that people carry themselves, the way they relate to the world around them.

I don't think I anticipated the extent to which I would learn how to be a grown up from all my fellow guards. I really loved the job. Why would I need to do anything else? I get to come here and think my thoughts and nobody's pushing me around.

[Even still,] seven or eight years ago, I got serious about writing this memoir [and left the Met in 2019]. I wrote two-thirds and I shopped that to agents. I knew some people, but actually cold-called a million agents and eventually found one.

Photograph by Tara Bringley.

I wrote it for 18 months, and we edited it in six months, and we had to wait a long time for Covid, and then it came out. I want to write another book, but I don't want to be forced to write it quickly. I want to do something to make a little money to just float along. I'm leading a lot of tours. There are people that read my book and want me to tour them around the Met. I'm also doing occasional public tours. I just wrote [and organized a tour of sites related to] Walt Whitman and Herman Melville in Lower Manhattan and Brooklyn.

My life is still the same. After my experience with my brother, I almost had a principled stand against being too ambitious because I didn't want to fall into the trap of trying to scrap my way towards some office position. Because what does it really add up to? What matters is still basically my wife and my kids and my friends."

in your life?

in your life?