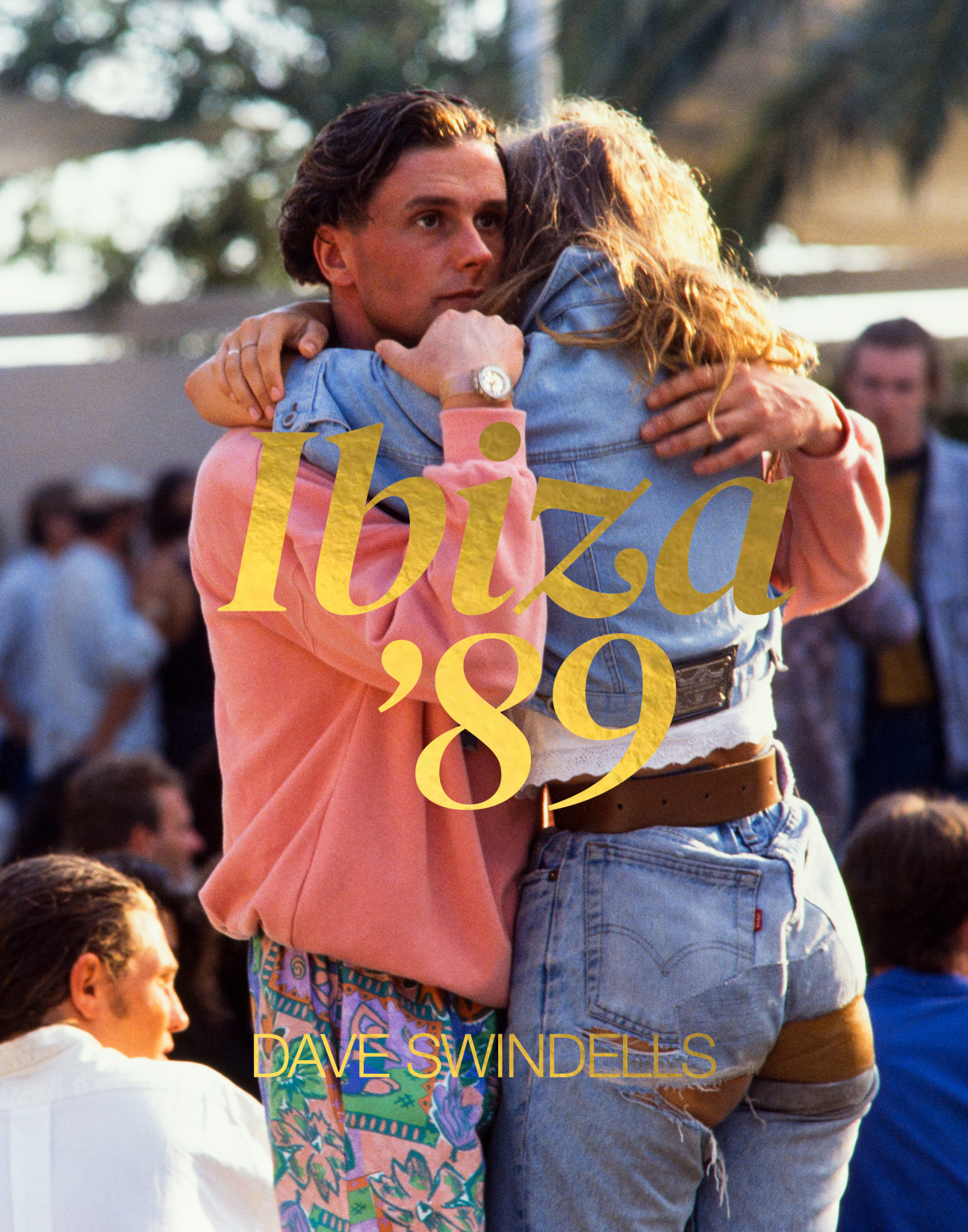

Music festivals are all fun and games until it's time to try and remember what the hell you did the whole time. Legendary photographers Paul Misso and Dave Swindells sat down with CULTURED to try to piece together their trips to Glastonbury and Ibiza following the release of Misso's new book, In the Vale of Avalon: Glastonbury Festival 1971' and the third edition of Swindell's classic, Ibiza 89' . As the Glastonbury Festival reaches its climax this weekend, nothing could cap it off better than two individuals who captured the most iconic festival moments of the '70s and '80s.

CULTURED: How did the two of you first cross paths, and how did you become familiar with one another's work?

Paul Misso: Well, we only actually met last Wednesday.

Dave Swindells: We didn't know each other before these books were planned and put together. We're both photographers who've been intensely involved in particular scenes and situations, which is a kind of bond straight away. We both know that feeling of desperately wanting to capture what's going on and the spirit of it. Paul was at Glastonbury for ten days and shot 7000 pictures, that's 200 rolls of film. You can understand it much more now in the digital era.

Misso: I do not remember sleeping. I'm not even sure that I went to the toilet. I remember being a chaperone to Julie Christie, Oscar-winning actress, and I had to stand in the hedge gap to stop people from going when she was relieving herself. That's the one thing I do remember other than taking the pictures.

Swindells: To some extent, that speaks about what kind of experience Glastonbury in 1971 was; in other words, an awful lot of people couldn't remember very much because they were either so stoned or…

Misso: All sorts of reasons.

Swindells: That's part of the crazy reality of that festival.

CULTURED: Paul, describe your decision to publish your photos in this book. And specifically, why now?

Misso: Because I was asked to. It's as simple as that. I've had these pictures for 52 years. They're [the photos] old friends.. I know them intimately. I put them together in scrapbooks. I didn't think they would ever get published as a whole. It had been such a long time that they were sitting in a drawer…I just hadn't thought the idea would happen. Then I went to my local lab, down here in Brighton, with two DVDs of all the images. I said, "Is there anything I can do with these?" I don't know why I was spurred on to say that, but I said it to one of the guys there, who happened to be a really good techie. He said, "Look, give them to me. I'll put them on the computer, and we can see what we can do." Ten minutes later, he handed me two new discs. The owner of the lab said to me, "Do you mind if I show these pictures to other people?" and I said, "No, fine." That's how the idea was found. They got a hold of the pictures and petitioned me to publish them. I said, "Yeah, sure. Carry on."

CULTURED: Dave, I have the same question for you. Why do you feel this moment is a good time to revisit that period and release a new edition of your book?

Swindells: My book is a third edition, but I've added some pictures. We got this together during the lovely pandemic when everyone had an opportunity to look into their archive because what else would we do? So I'd already been in touch with the idea, and they'd been fans of a book I did about 10 or 11 years ago. It only had about 30 pictures from Ibiza, and they asked me when I went for a meeting, "Hey, have you got any more pictures?" and "How about it?"

CULTURED: You both specialize in these underground communities. What is it about that work, specifically, that captivates you? Is there a particular moment you vividly remember that spoke to you in some way or left some impression on you?

Misso: I was brought up in London. I went to college in London, and I started my first studio in London in 1965. I became a fashion and advertising photographer pretty quickly and did well during the '60s. It was a very small world—everybody who'd been at art college and was involved in music—we all knew each other. We were highly conscious of the times: the Vietnam War, homosexuality being illegal, capital punishment still being around, and CND [the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament] being bashed about by police. We were a product of the walking wounded of the 20th century. That's what I named the British at the time. Our parents were the walking wounded. They had actually, in a way, saved the world from Nazism.

So we were a generation who were really conscious of what was going on and what changes were occurring. For instance, how fashion had become a statement and how the beat poets were writing stuff that resonated. They were the people who were hitting our consciousness, and we were not taken in by the establishment. So inevitably, the underground was prevalent in our lives.

Swindells: It's connected because Glastonbury Festival was a counterculture experiment in many ways. It was a response to massive events like Woodstock and the Isle of Wight Festival. These were really massive crazy-large anarchic events. The first Glastonbury was a free festival. That was what set it apart straight away. It had these aspirations to celebrate in an almost medieval way, that medieval revelry, a meeting place.

Misso: It was about a resurgence of a spirit, the spirit of Old England pagan rituals, Christian rituals. It wasn't just a music festival, it was about expanding consciousness. That was the ethos. Andrew Carr, the organizer, was effectively a hippie aristo.

Swindells: There are some little parallels without trying to ridiculously stretch things. Ibiza was a place that was on the hippie trail in the seventies, one of the places people went to, in their roundabout way to go and escape. There's a definite spiritual vibe there. And similarly, Ibiza, even by 1989, was already very much like Glastonbury was by 1989, a massive and, to some degree, very commercialized operation, in the sense of there being the biggest club in the world. But you know, obviously, people argue, some people say, "Oh, you know, these massive festivals, they're not the spirit that they once were, they're not guided by the spirit and the ideas." Would you agree?

Misso: I mean, look, one of the things that I like to point out is that the people who run the particular areas of the Glastonbury Festival are the people who know the ethos, they've been living it for years and years and years, and they've been honing their trade. Everywhere you go, you still get this sense of a magic kingdom centered around that spiritual resurgence.

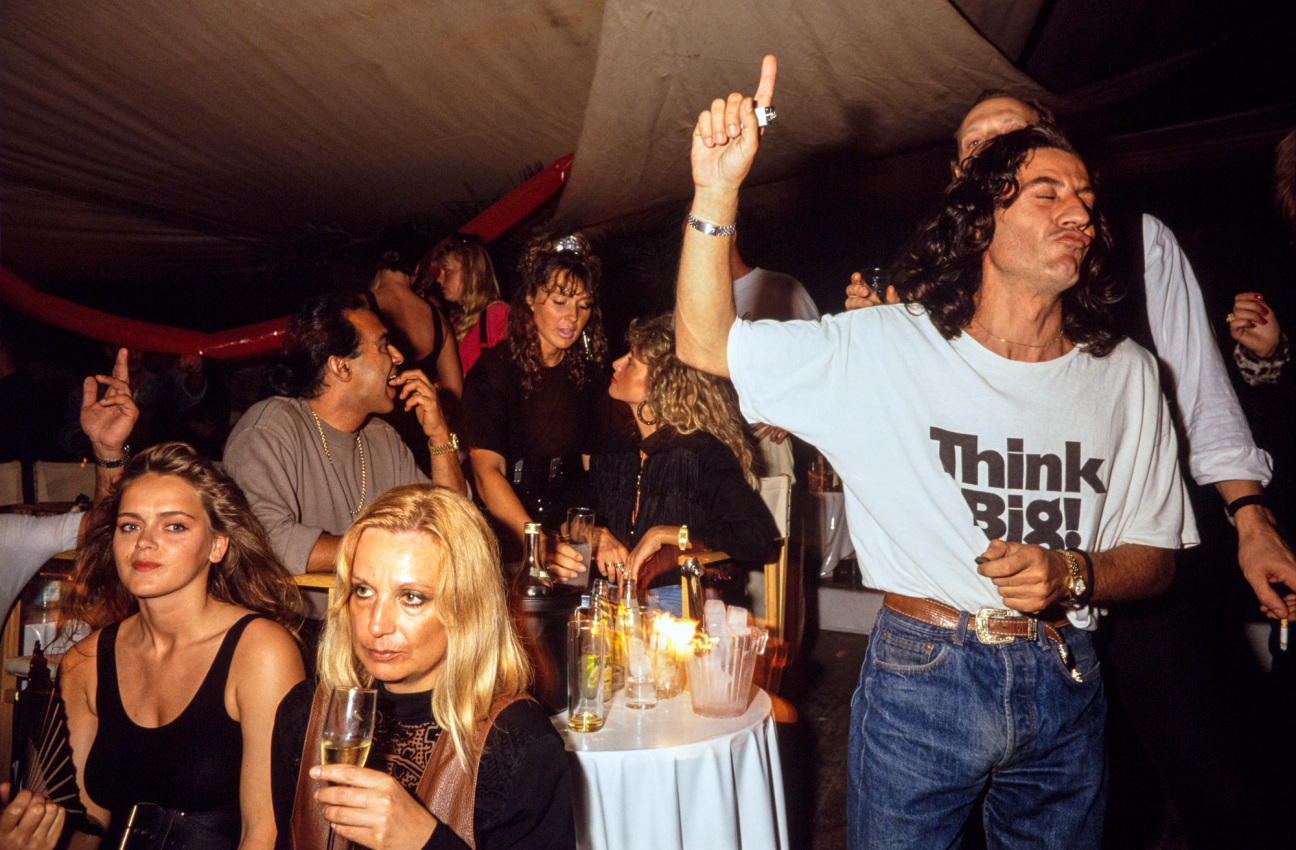

Swindells: The other thing that I think about is the sense of continuity. Your magic kingdom phrase really resonates because it reminds me so much of it being a place where magic can happen. I often think that's what nightlife can be. It's also a safe space where people can express themselves and their sexuality and their different genders, or however, they wish. That was definitely the case in Ibiza and Glastonbury.

Misso: The bands were playing at nightclubs because where else? They didn't have any venues other than nightclubs to play in. They were magical places. They were the places we went.

CULTURED: How did you balance being in those crazy chaotic atmospheres and taking photographs?

Misso: It totally changed my life. The last time I shot any fashion was after Glastonbury. I've done a bit here and there, but that was not my thrust anymore. My thrust became continuing what I'd done at Glastonbury. I hope that I've actually captured something about our humanity, something about our specialness, something about people. Whoever they are, whatever gender they are, whatever color they are, they've got something special, and that was what I was trying to do consciously.

Swindells: Absolutely. It's also interesting because you took 7,000 pictures, and at one stage, I was thinking, Wow, this is great. You'll be able to do many more books with all these 7,000 pictures. But of course, you don't have them anymore. Over a period of 10 years, you moved 50 times, and amongst all those moves, a lot of things just went missing.

Misso: My books, my records, a lot of my pictures, you know? I just couldn't carry it around.

Swindells: There's a certain kind of magic in that you've got anything left.

Misso: That's right, Dave. Yes. It's a miracle that I've actually still got those.

Swindells: With all those crazy moves, midnight flits, or whatever was happening.

Misso: That's my next story if the world can bear it.

Swindells: Well, that's another thing, though, isn't it? You were photographing fashion and advertising, which are very controlled environments. The principle behind festivals like Glastonbury is "let freedom reign."

Misso: Absolutely. Ibiza's the same. The flavor of your book is not dissimilar to mine.

CULTURED: In those moments, were you looking for something specific to photograph?

Misso: I think it's the latter. I believe that something spoke. I remember the particular pictures that I've chosen. 80% of them, I remember the moment of taking the picture. It's the only thing I really do have a memory of. There's something about the situation which speaks of the essence. It speaks of the spirit of what's happening.

CULTURED: Dave, was your experience similar?

Swindells: One little difference is that I was using flash. That changes things a little bit. In a way, the moments when I was happiest taking pictures were in the morning after being out all night, and the club still carried on. It feels like a luxury when you can take pictures without using flash, without disturbing people in the same way. Inevitably flash is quite intrusive. Without flash you can take candid images, which can be lovely. Whether people are aware of it isn't necessarily important. People can perform for the camera, and you can still get amazing pictures. The pictures can still speak and have a genuineness about them. It's not that you must be some fly on the wall where you're secretly snapping somebody.

But nonetheless, those couple of hours when I could take pictures without flash were fantastic. It was such a treat. It's a special time anyway, at seven in the morning. People have been dancing all night, and the sun is coming up. These are magical times. That's what I was there to capture. I remember taking all of the photographs partly because I had steered clear of Ecstasy and all that because, lovely though it might have been, I couldn't focus and do the other things I needed to do, calculate flash distances and all that stuff.

Misso: Or you don't even remember where you'd left your camera.

Swindells: Exactly. "Oh, dear. There goes the job."

Misso: "I have a camera with me!"

Swindells: Often in clubs, you'd be quite relaxed and leave the camera over there, knowing that people are mostly ok, and then you think, Oh, my God. Where's my camera? And run around. Going somewhere and having a kind of experience where you go out, not really knowing what's going to happen, is really important for me. Sometimes it feels much harder to do that now because people book their experiences months ahead. But going out and not knowing where you're going to end up is also a wonderful thing. Most of the people who went to Glastonbury and to Ibiza experienced that. It's the whole notion of living in the moment, which was definitely happening right then.

in your life?

in your life?