When art history student Alma Zevi sat down to write her senior thesis on the Swiss artist Not Vital, she didn’t know she was beginning the text for Not Vital: Sculpture, 2023, the most comprehensive book on his work to date. Nor that it would take more than a decade, several jobs, and a global pandemic to finish. And if she did, the curator and dealer doubts she would’ve even started. Her selection of Vital was motivated at the time by a bout of imposter syndrome, as she confides in her introduction to the heftiest artist book this journalist has ever received: “Most of my fellow students were writing about the Old Masters. I was both terrified and baffled—I certainly would not be able to put forward any novel academic findings on Titian!” Luckily, she instead became the world’s foremost expert on Vital’s genre-defying oeuvre.

The book, like her relationship to Vital, is deeply personal. It leaves no stone unturned, a privilege that only comes with having organized an artist’s archive, Zevi’s first job out of school. Without this insider track, we wouldn’t get the intimate moments, like a glimpse of Vital’s childhood drawings: pictures of camels crossing arid, desert wastelands, already dreaming of places far away from his Alpine nest. Seemingly innocuous details like these foreshadow the larger themes that still drive Vital today: his lifelong adoration of animals as walking shorthand for nature’s divinity, his insatiable peripatetic itch enmeshed with a devotion to site-specificity. (Vital maintains studios in Brazil, China, and Switzerland.)

Having never been part of one movement or tied to one genre, the monograph benefits from the color and depth Zevi gives the well-trodden lines of his resume. For instance, it dawdles on an image of his friend and mentor Cy Twombly taking in Vital’s Venice Biennale installation, and reminds the reader of his stint in Patti Smith’s band, when Vital was still working out of the loft on Broadway a young Annabelle Selldorf designed for him. These personal moments aren't graphed on top of the pomp of later analysis, but instead left in the raw for the reader to draw their own conclusions. “I want to create an environment for the work but not force connections or specific readings,” says Zevi. “My greatest hope for this book is to provide a fertile jumping off point for others’ interpretation.” Vital’s work, after all, is never about foregone conclusions but about the odyssey: a sculpture, an image, or a word can send us on.

Here is a peek at some of the 400-plus images included in Not Vital: Sculpture, as narrated by Zevi.

ON PERFORMANCE

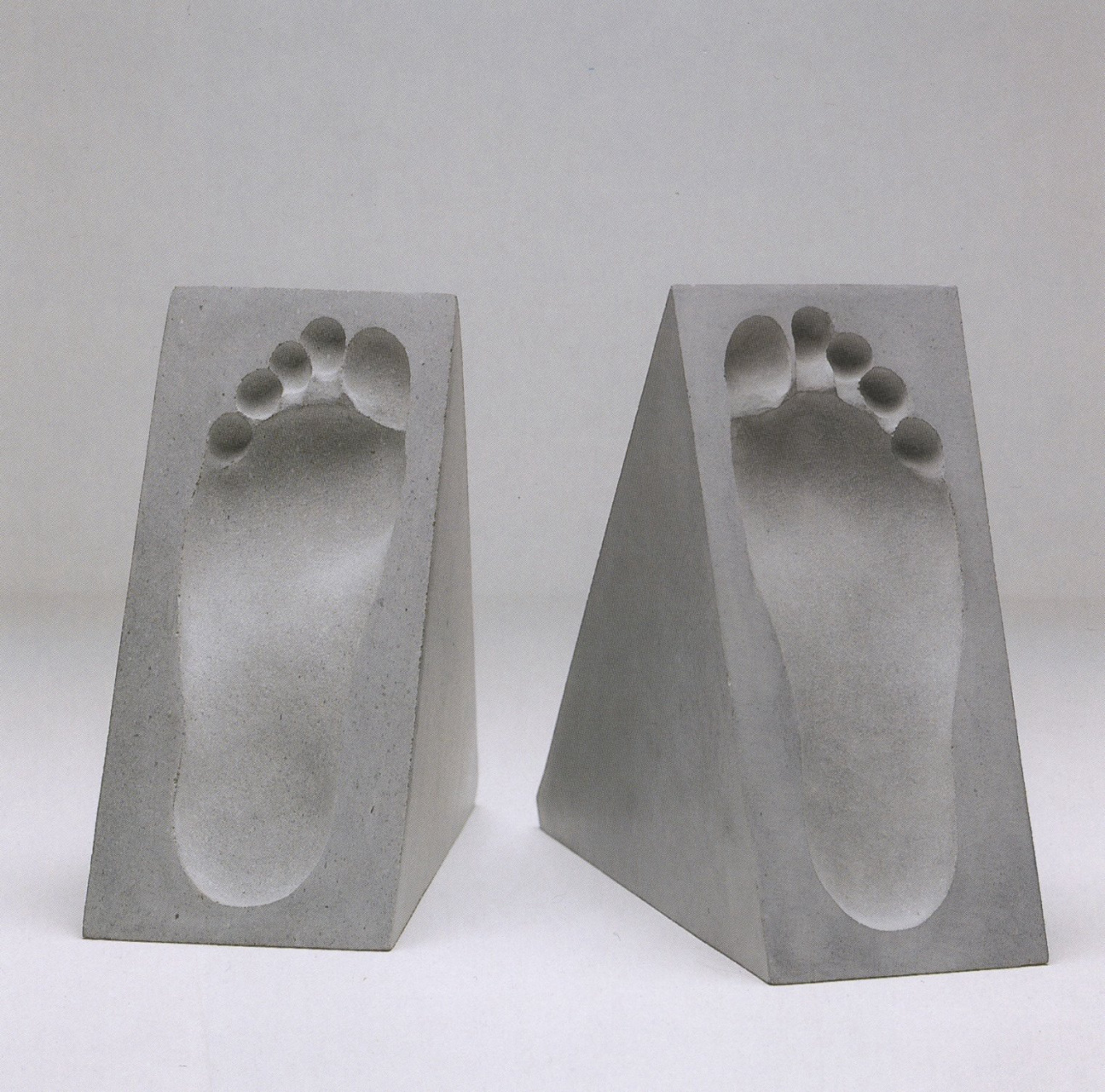

"S-charpas per ir sul Piz Ajüz (Boots for Climbing Piz Ajüz) is a deeply autobiographical work, a characteristic that begins with the imprints of Vital’s feet, which contribute a highly personal aura to the work. The 'story' as to how this piece came about is recounted by Vital:

'Boots for Climbing Piz Ajuz, a mountain opposite Sent. All my life, I had a view of the mountain from my bed. I have climbed it only once, at night. The imprints of my feet in two pieces of granite form part of a climbing boot in the shape of a mountain. Total madness to walk around like that.'"

ON MYSTICISM

"Animal motifs recur throughout Vital’s work and are directly related to the Engadin’s varied fauna. Such representations in works dating to the 1970s and 1980s have already been explored in the previous chapter dedicated to New York, so here I will begin with Animal Holding Large Egg, 1999. The straightforward title juxtaposes the rich conceptual and historical references addressed in this piece. The seemingly simple shape prompts viewers to absorb the sculpture’s elegant formal presence. This tug-of-war between concept and an appreciation of form and material is frequently noticeable in Vital’s work and is often further denoted through clear, descriptive titles. The egg has references to Christian iconography (symbolizing the resurrection of Christ), as well as associations with today’s Easter egg.

In Animal Holding Large Egg, there is an aperture created beneath the 'egg' as a reminder of its structural integrity—brittle but strong—as ably exemplified by the famous anecdote of the Renaissance architect Filippo Brunelleschi, 1377–1446, who used the form of an egg to demonstrate the theory of engineering for the new dome he was building in Florence. In our case, the upside-down shape seems to act as a plinth for the egg, giving it a delicate, mystical significance. Does this symbolize the trophy of new life? The way the two elements interlock certainly relates to the circularity of life. Both the animal and the egg are unidentifiable in that the animal element could represent a goat, deer, or cow, while the huge egg evokes that of a prehistoric animal or dinosaur."

FAMOUS FRIENDS

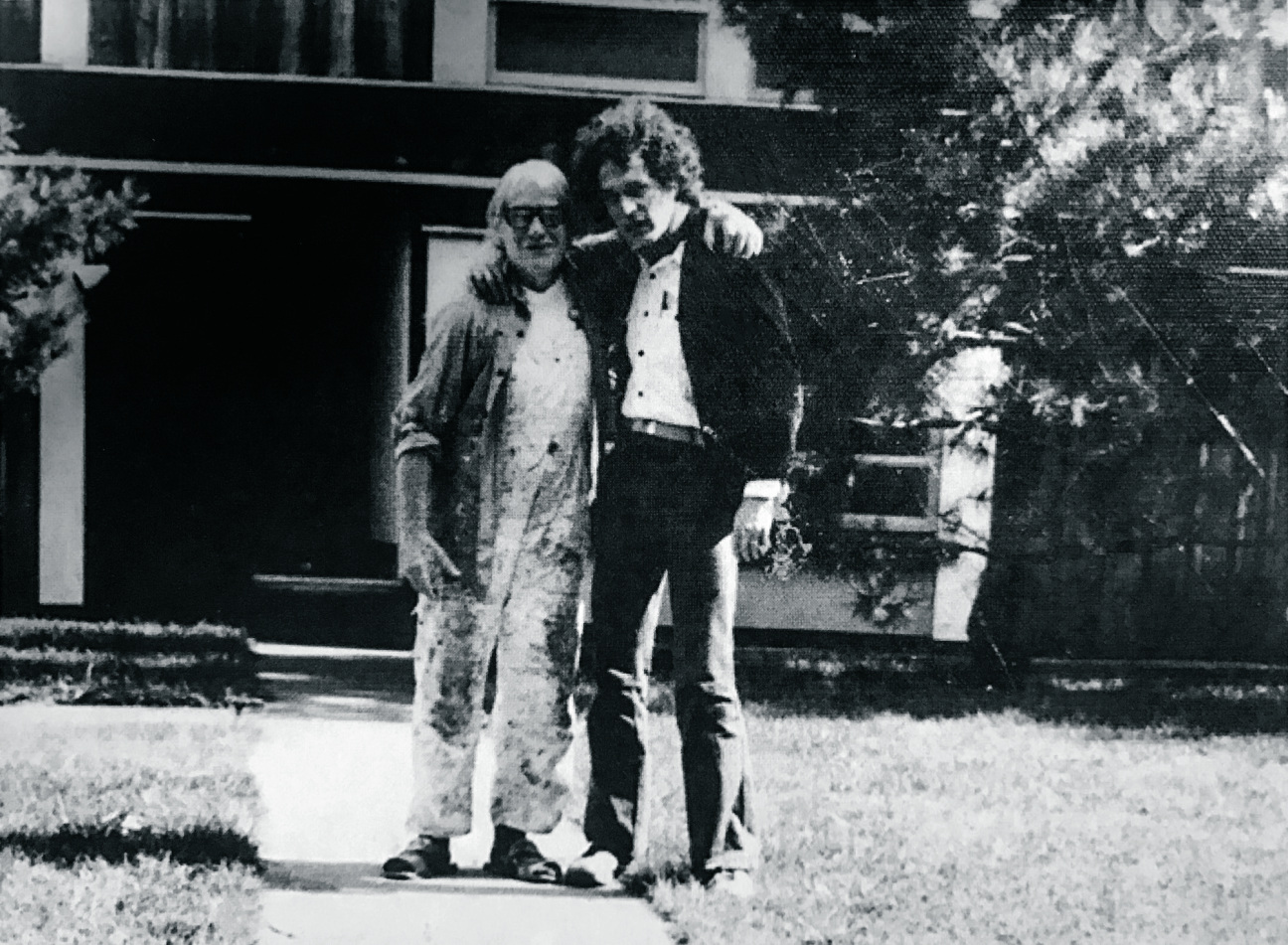

"Soon after arriving in New York, Vital spent a formative week in Springs, East Hampton, with Willem de Kooning. The experience came after meeting the famed 70-year-old Abstract Expressionist along with Salvatore Scarpitta, whom he met on his second day in New York. De Kooning’s work was not fashionable at the time because of Pop Art’s contemporary appeal. Two things about his artistic practice were particularly unfashionable: figurative sculpture, and his use of bronze. Incidentally, Vital would go on to work with both throughout his career. Indeed, one could say that Vital’s early work borders between representation and abstraction, hinting at de Kooning’s style. In those days, bronze was considered antiquated and bourgeois as a material and out of sync with the Minimalists’s use of industrially produced sheet material such as aluminum and steel. During their week on Long Island, de Kooning would ask Vital for his opinion on his ongoing paintings, specifically regarding the choice of certain colors.

This was something of a shock to Vital, who was used to a hierarchy among artists in Europe, where an established artist would never ask a younger one their opinion. Such an expression of openness—characterized as typically American—was at once liberating and exciting for the young Swiss artist. During the time of the visit, de Kooning also showed Vital a finished sculpture in his studio, pointing out how he had left his gloves in it, thus making them part of the work. This became an important memory for Vital. Could such a meaningful anecdote impact his work? Perhaps such an impact could be observed in the elements of surprise and informality in Vital’s output and the confidence in actions that are quietly subversive."

FAMOUS FRIENDS CONT.

"In Untitled/Cairo, 1989, Vital creates a single sculpture by combining three objects—two terracotta vases and a wooden pole—and painting all three components white. By fusing the three pieces together and using paint as the cohesive visual element, the artist brings together the seemingly discrete pieces and transforms them into a distinct sculpture with visual and structural unity. This approach to making sculpture with readymade recalls Cy Twombly, a friend of Vital’s and an artist he admired. The vases are detached from their function since there is no way for them to hold anything when their apertures are closed by the attachment to the stick. Terracotta is a material long associated with both ‘decorative’ sculpture and functional vessels throughout all ages and cultures. Indeed, a theme that Vital begins to explore in the 1980s is functionality versus decoration—and indeed, the negation of functionality. Vital plays with this tension between the two, resulting in this surprising work of art. "

ALPINE ROOTS

"One’s first response to The New York Calming Room, 2007, is paradoxical, as New York is not known as a place that is calming or relaxing. Vital constructed this room from stone-pine, an Alpine wood that is commonly used in the Engadin for paneling house interiors. Upon entering The New York Calming Room, the visitor is immediately struck by the distinctively rich and soothing fragrance of the wood. In this work, the olfactory experience is as important as the visual. The paneled exterior of the chamber is painted white, excluding the knots in the wood, leaving them visible. This painstaking process creates a rhythm to the surface simply by following the natural pattern of the wood. In doing so, Vital once more highlights the beauty that can be found in nature.

In the ceiling, many of the knots have been cut out, leaving holes to allow light to enter the chamber. These recall constellations of stars, pointing to the artist’s long-standing fascination with the Cosmos. This work shows Vital’s identity is an amalgam of his life in both New York and Sent. It is the notion of identity, and perhaps the heimat concept, that is at the heart of Vital’s concern as a ‘nomad’ from the Engadin. Vital went on to create Calming Room in 2018, located in his castle in the Engadin."

IT'S PERSONAL

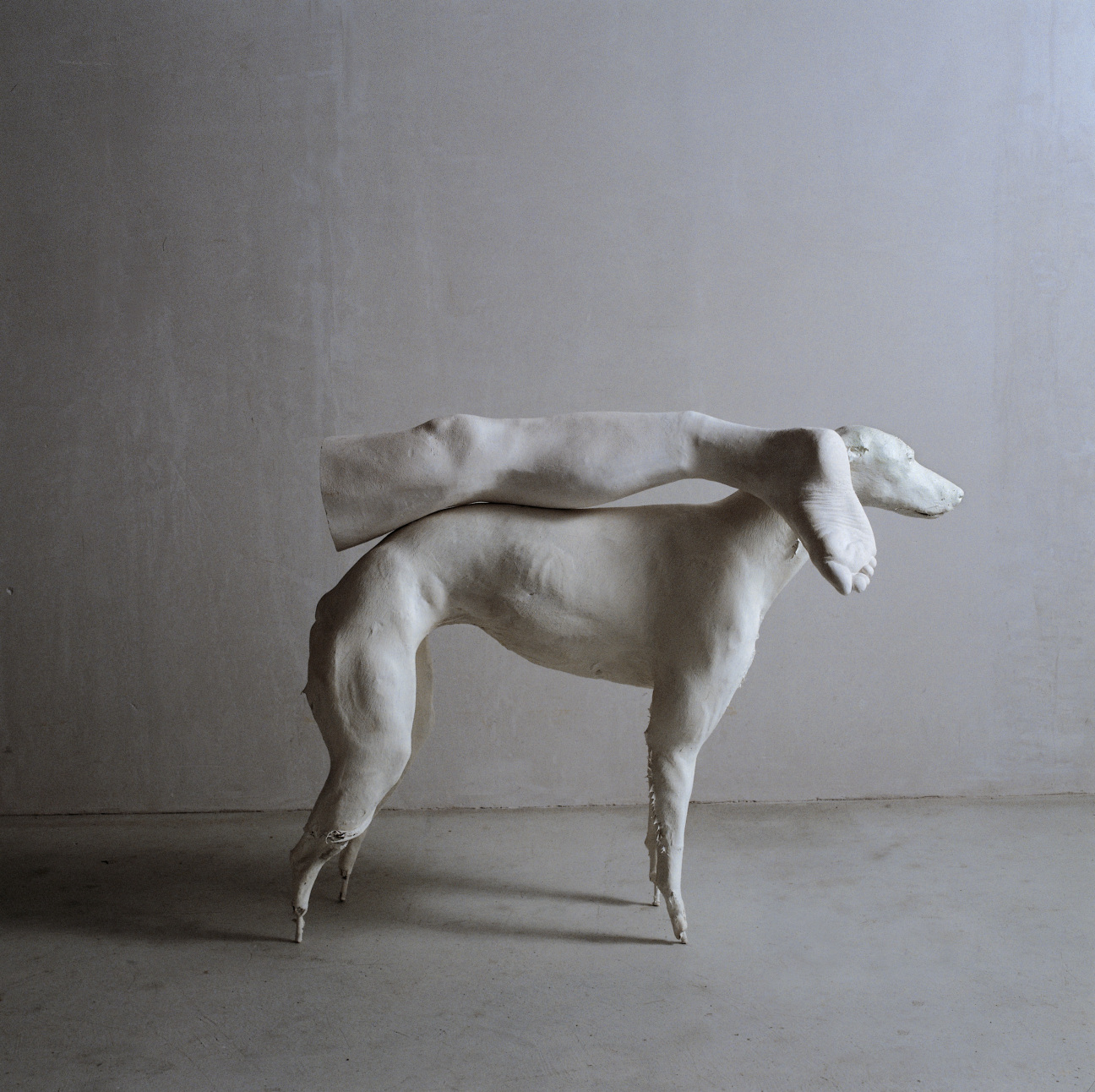

"This work refers to a skiing accident in which Vital twisted his leg and was badly injured. Many years later, he had a dream where he relived the experience; in the dream, he was rescued from the slopes by a greyhound, however. This unconscious re-experiencing of a traumatic incident appears in the sculpture, where a cast of the artist's twisted leg is carried on the back of a stuffed greyhound. This can be read as the redundant human seemingly reliant on the heroic animal. However, the dog has no feet, creating a sense of simultaneous movement and stasis in the work. The plaster makes the work fragile, which evokes the vulnerable narrative in this seminal work. This marriage between dream and reality, and the way that we process experiences, is crucial for a deeper appreciation of the piece. Such an interest connects to the artist's long fascination with Surrealism, especially Dadaism, which he has previously attributed as his greatest influence."

MAN AND THE LAND

"This is a readymade ‘house’ that Vital found in Niger and re-appropriated as an artwork by assigning it a new meaning. According to the artist, The 10th House offers a space in the rock in which he fits perfectly, and where he can even sleep standing up. The work’s title originates in the realization that this was probably the 10th house to enter into his oeuvre over time. The space—or house—has both a natural entrance and exit. Made of sandstone, it is among his most unusual works, as the artist usually prefers to manipulate found objects, but in this work, he elected to leave the space and work as a readymade. The 10th House also distinguishes itself in its performative aspect, which renders it among one of his more conceptual pieces: the photograph of the piece is as important as the rock itself and also illustrates Vital’s belief that a space can be a house the moment he can lie, sit, or sleep in it."

SCULPTURE AS ARCHITECTURE

"The term ‘SCARCH’ was coined by the artist to describe his unique combination of sculpture and architecture, an intersection that he returned to repeatedly. Over the last 20 years, SCARCH has come to prominence, and in the last 10, it has become a core aspect of his practice. Vital’s interest in architecture began in childhood but crystalized steadily over the years, leading him to develop a more formal research on radical theories of architecture. His arrival in Niger marked the beginning of his sculpture-building. This is the part of his practice that he later named SCARCH. When Vital decides to build a house—as he has done first in Niger and then in Brazil, Chile, China, Indonesia, and so on—he somehow always manages to make what most people would consider an impossible project happen, even in adverse situations. For example, in Niger, the workers could not understand Vital’s drawings for his house, so he traced the outlines of the foundations directly into the sand. This open and flexible approach, combined with a willingness to adapt, is critical in the conceptual and physical manifestation of the buildings themselves.

In 2003 he went on to build a school, Makaranta, 2003; followed by House to Watch the Sunset, 2005; House to Watch the Night Skies, 2006; House Against Heat and Sandstorms, 2006; House for 8 Brothers, 2006; and Mosque, 2013. All of these structures have varying degrees of functionality and lie somewhere between architecture and sculpture. The ‘function’ of these works, as well as their appearance (especially House to Watch the Night Skies and House to Watch the Sunset), recall the astronomical gardens in Jantar Mantar, Jaipur, India. The gardens are an astronomical observation site and house the world’s largest stone sundial, made in the early 1700s. When asked about these astronomical Indian gardens, Vital remarks they were certainly on his mind when constructing the SCARCH works in Niger. However, another reasoning he offers is that it felt natural in the desert to orient himself around the sun, moon, and stars."