It looked like a Denis Villeneuve film, the air filled with eerie pallor. New York, blanketed in otherworldly gloom, saw residents holed up indoors and putting masks back on for protection. The streets bore a striking resemblance to the peak of the pandemic, albeit with the addition of an ominous, apocalyptic hue. Despite the global rise in wildfire occurrences as climate change worsens, the city seemed unprepared for the smoky veil that fell upon it. And though bars and restaurants remained open to patrons eager to drink martinis and people-watch, there was something missing from the city’s signature roar: fewer voices on the streets, amplified siren blares. Photographers braved the surreal landscape to capture these moments, so CULTURED invited them to share their experiences navigating their profession during yet another unprecedented time.

Gili Benita:

Benita is a CPOY-award-winning photographer who contributes to The New York Times and has worked with HBO, I-D, and Aint Bad Magazine. He was a Finalist for The Alexia Grant this year.

“On Wednesday, I had an early sunrise shoot in the Rockaways. The air was smoky and felt strange, but this was just before everything became orange. At the beach, I mostly photographed the sky with my phone. It felt more mundane, and the sky was deep blue. As the sun rose, a thick orange layer painted the sky. Using my phone to photograph has become a tool to save small memories and checkpoints, and that day felt like a weird moment I should save.

We react by taking a photo because that’s how we process and remember things. In any significant event, the best camera is the one that you hold at that moment. In those images, the orange gradient slowly took over the sky, followed by the bright orange-red sun. It felt so special because it was just a brief moment. Fifteen minutes later, the light completely changed.

In a way, it felt like some kind of social event cast against one of the most apocalyptic views we’ve seen. Everyone was posting about it, the memes went wild, and we all became overnight specialists in AQI.”

Chris Bernabeo

Bernabeo created the zine Lylas, photographed Alison Roman’s Sweet Enough cookbook, and has worked with Vogue, Interview Magazine, and other publications.

“If you stuck it out in NYC during the pandemic, you had to have some sort of initial flashback to those feelings when the whispers of shelter-in-place started. It didn't hit the same impending doom tones as that era, but as a New Yorker whose favorite mode of transportation is walking, hearing that the air outside your door is harmful is never a fun sentiment to start your days. This event felt like a general culmination of months and weeks of these ‘end of times’ conversations I’ve been having with other creatives.

We’ve had this beautiful, true NYC spring, where everyone has been able to step back into the magic of the city when the weather gets nice again. But sitting in the parks and outside the coffee shops and bars, I’m having a lot of conversations about how scary slow some of us are in the industry right now, how quickly A.I. has been ushered into a lot of creative fields, the bubble bursting on streaming platforms with the film and television industry. I was on the phone with my friend discussing this yesterday as that burning orange glow filled my apartment, and it just felt like the sunny spring scenery of those discussions in those dreamy places finally caught up with the unfortunate and terrifying consequences that are resulting from them for a range of creatives, let alone the general state of the world.

I’ve always been fascinated by how alone you can feel in a city of 8 million. I don’t find that to be the dark or depressing notion it sounds like though. I find it to be quite beautiful. We live in this ever-changing metropolis that is always challenging us in some way but if you truly love it here, it’s what keeps you coming back for more. The feeling of silence in these images is striking, because it’s so rare that it is. I’m always more calm within the chaos.”

Garritano's work has been featured in publications including The New Yorker, The New York Times, and The Atlantic. His commercial clients include Bose, Equinox, and MoMA.

"I think there’s been some comfort in knowing that this is going to be quite a temporary thing and that our skies won’t glow for long. At least, for now. As is typical, New Yorkers seemed mostly unbothered. It’s a generally thick-skinned bunch, but I’ll personally take the opportunity to be aggrieved by any minor thing. I had a picnic cancel. Online of course, you’d think the four horsemen had arrived. Folks have just been going about their days as far as I’ve seen, with maybe a few additional curses murmured.

It's always so enchanting when mother nature rings our bell and reminds us of our rank, especially in a place like NYC where she rarely does so. For these recent images, I used flash-lit subjects as sort of control group for how wild the sky was. I’m looking for that sweet spot on the irony-sincerity spectrum. Lately I’m trying to be looser and more playful in my approach and this was a serendipitous set of conditions to pick at that—smelling the roses while the world burns."

Laraib Irshad

Irshad is a writer and photographer who was selected as a finalist for the Women Street Photographers Annual New York Exhibition this year.

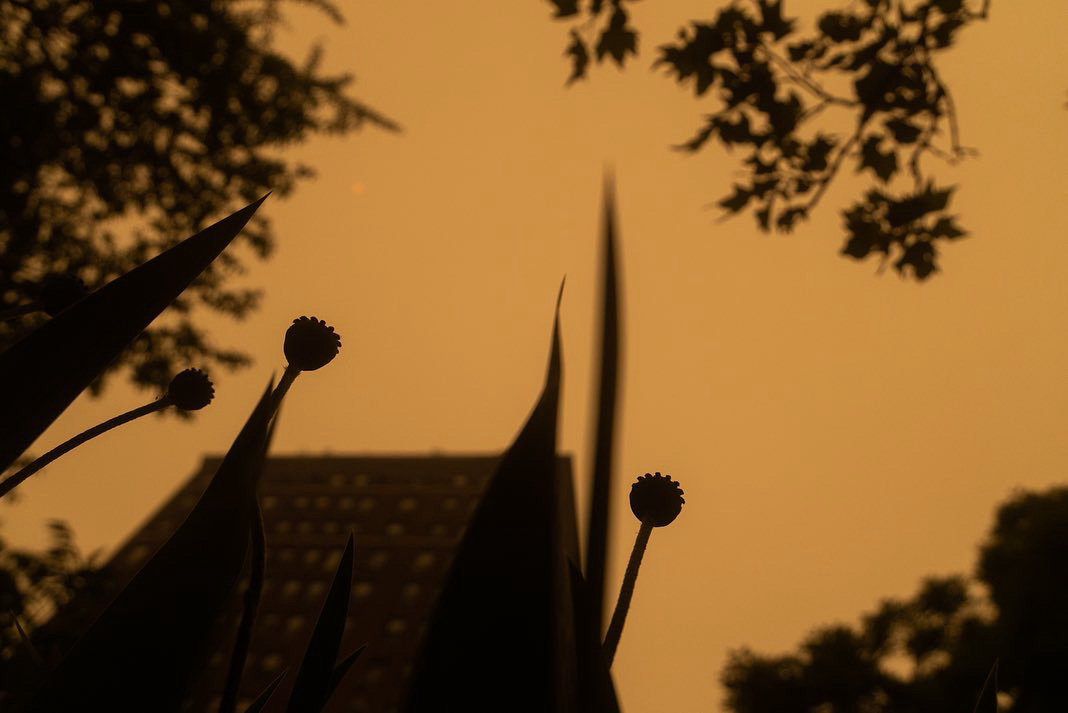

“The Verrazano-Narrows bridge, an iconic architectural structure in New York, was hidden in this smog, and the normally visible Manhattan Skyline from Fort Wordsworth in Staten Island was completely [obscured]. To me, capturing these images offers a tangible memory for those who lived through these two smoke-filled days. There's a hidden beauty to the photos, yet a sense of the unknown. It’s an uncertain feeling mixed with curiosity and caution.

In my 30 years of being in New York, this has never happened. Capturing this moment was very surreal. Driving to Fort Wadsworth, I noticed a shift in people. On one side, there was awe and amazement, while on the other, people wore masks and protective eyewear. I hope this will be a once-in-a-lifetime event. The images, vibrant with yellow and hints of orange hues, will forever remind me of this strangely bizarre yet beautifully terrifying day.”

Tommy Rizzoli

Rizzoli has photographed for various brands and publications including Tiffany & Co., Adidas, and OnlyNY.

“The smoke made me slightly more hesitant to spend as much time outside as I normally would. Much of my life in NYC revolves around walking and biking, and taking pictures while doing those activities. This event, however, left people like, ‘Whoa this looks apocalyptic,’ especially Wednesday when the sky turned to a deep orange in the middle of the day. It looked like Blade Runner 2049.

Whether I'm shooting editorial/campaign work or street photography, I always want there to be a level of realness in my images: real happiness, real sadness, real anger. I am fortunate enough to spend a majority of my time photographing my friends too, especially for my editorial work. This means a lot of the time the emotions that show in my images are real and natural. This week was different mostly because I have asthma and felt like I had been smoking cigarettes the entire time I was outside.”

Clémence Foucart

Foucart is an art photographer based in Paris, France.

“I am not a New Yorker, but I have connections to the city that bring me back to it now and again. The smoke made me anxious to go outside and had me question if natural disasters like this will become a part of our day-to-day experience. There is an eerie vibe in the city. It seems that people are concerned by the smoke, but also confused by the lack of information. There was no clear sense of what to do, how to prepare, if to take shelter. The sudden appearance of masks brought up feelings from the pandemic. It was surprising that many parts of New York kept going; stores were open and workers were out even in dangerous conditions.

I wanted to document and encapsulate the unsettling feelings the moment brought to me. The color is off and the lighting in the photos feels otherworldly. The event itself is terrible but also astonishing, as it makes everyone pause from their day and look. There is a kind of loneliness in my images; most are devoid of people and you get the sense that the outside feels dangerous.”

in your life?

in your life?