“New Photography,” the title of the Museum of Modern Art’s long-running survey, has always doubled as a declaration of intent. This is a bellwether show, an event where emerging trends in contemporary photography coalesce into era-defining themes. In 2010, the topic du jour was the porousness of borders between editorial, documentary, and commercial pictures; five years later, it was the “Ocean of Images” flooding the Internet. In 2018—the first iteration mounted after Trump’s election—the lens turned both political and existential: How could photography “capture what it means to be human?”

It’s much harder to plot this year’s “New Photography” exhibition in the zeitgeist. At first blush, the 27th edition of the series seems like a departure from its predecessors. It’s the first to adopt a strict geographical framing, with all seven featured photographers maintaining a connection to Lagos, Nigeria. And it makes no claims of “discovery”—that colonialist idea.

Under the organization of MoMA Associate Curator Oluremi C. Onabanjo, the exhibition steers clear of totalizing narratives about its artists or the port city they share. When asked about the decision to highlight Lagos, Onabanjo hedges: “It was less about determining the place as the object of my interest,” and more about spotlighting “seven artists who I feel have interrelated conversations, whether through form or concept.” Lagos, she says, is just the “context that allowed them to breathe together.”

But for gallery-goers, the city offers a way in. “Focusing on an artistic scene out of the city of Lagos allows us to ask questions of the image that perhaps we haven't before,” suggests the curator. Her response echoes one of the show’s primary goals: to “[apply] pressure to the notion of the photograph as a document.”

As far as exhibition theses go, Onabanjo’s is, by design, quite modest. At its core is an idea intuitively understood by anyone with an Instagram account: that the way we use photography now is different than in the past. Whereas images were once treated as records of people and places, today they are fluid tools of communication, commerce, and propaganda. The show suggests that it's time for the way we think about them to evolve, too.

Several artists in the show operate in the documentary tradition, but do so “only to expand it,” notes Onabanjo. Among them is Yagazie Emezi, whose photographs on view chronicle the 2020 #EndSARS protests against police brutality in Nigeria, and Akinbode Akinbiyi, who, for the last 38 years, has trained her lens on life at Lagos’s Bar Beach. These artists’ works “are more immediately recognizable to a viewer as images that ‘document,’ but you see that their conceptual positioning is different,” Onabanjo points out.

Another artist working in this mode is Amanda Iheme. Her “The Way of Life” series captures aging buildings in Lagos, all erected under British colonial rule. One shot focuses on Casa de Fernandez, a historic 1846 home of an Afro-Brazilian slave-owner that was demolished in 2016, the year after Iheme snapped the photo. “It was just discarded like it was nothing,” says Iheme in an accompanying audio interview, lamenting the familial histories lost with the structure. For her, buildings have lives that mirror humans’ own: “I wanted people to see that there is something important that buildings have to tell us about who we are.”

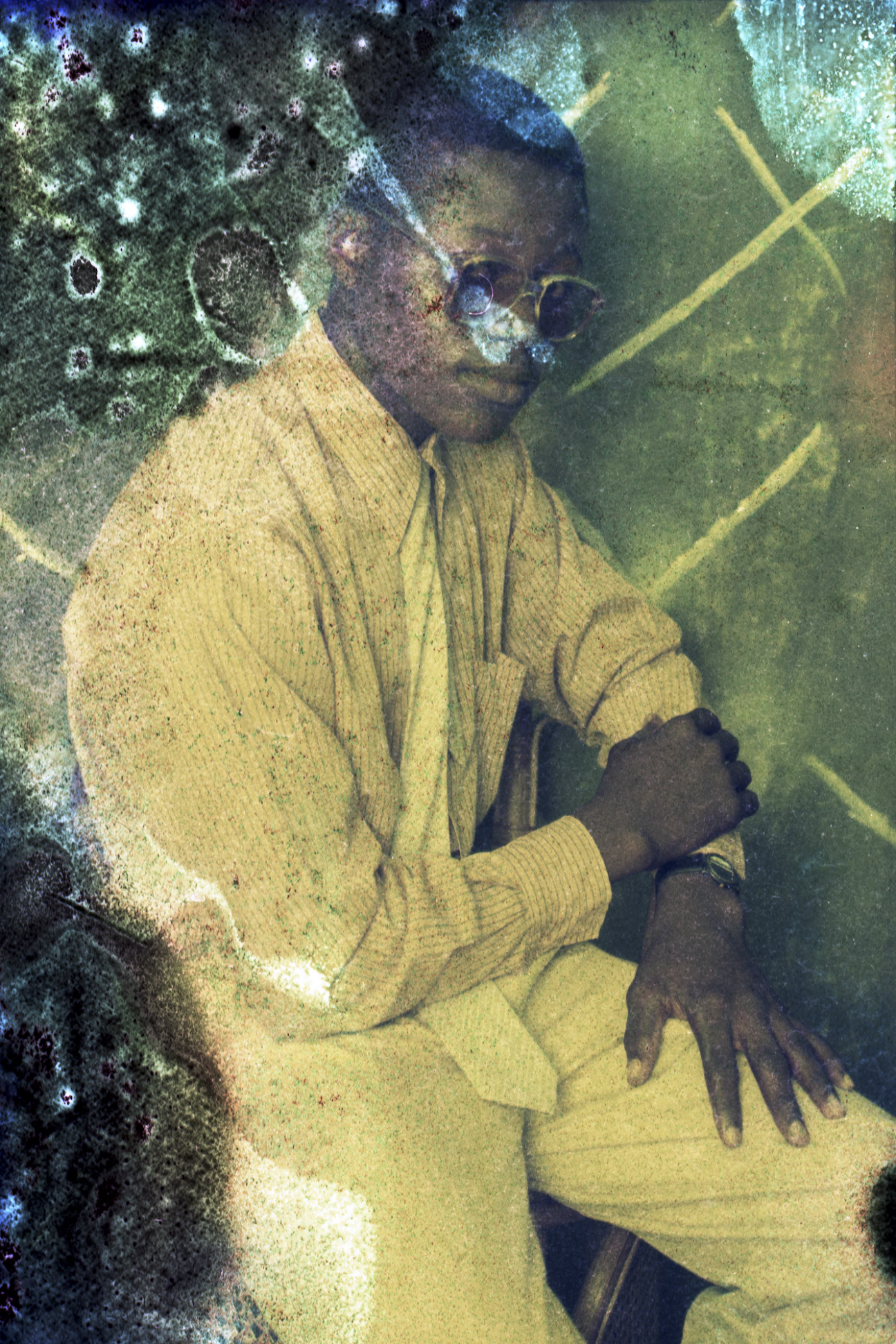

A similar sense of loss frames Karl Ohiri’s “The Archive of Becoming,” a series of prints made from negatives discarded long ago by portrait studios transitioning from analogue to digital photography. Now decades old, the professional gloss of these images is gone; in some cases, so are the faces of their sitters. What fills the frame today are scratches, stains, and bacterial blooms born from years of neglect in a humid climate.

“The ‘Archive of Becoming’ emerged from realizing that, through this abandonment, there’s something quite historically important and something quite beautiful going on,” the artist explains in an audio interview. Indeed, in Ohiri’s hands, the photos are no longer just portraits of individuals, but something more: portraits of post-colonial Nigeria reclaiming its identity after establishing its independence in 1960. A series of sculptures by Kelani Abass does something similar, embedding vintage family photographs in wooden letterpress cases to draw attention to the ways in which images codify history.

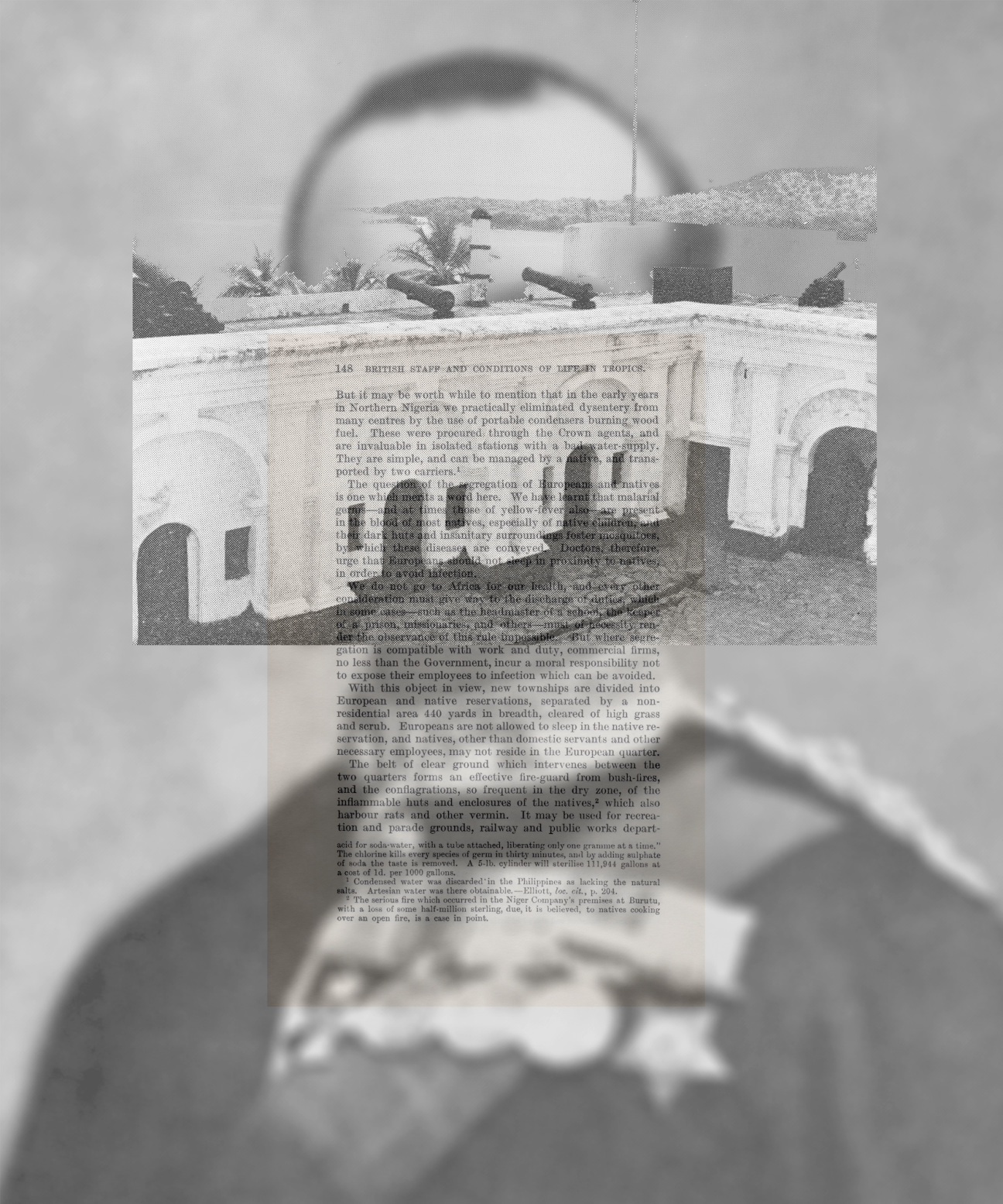

Abraham Oghobase also looks to the archive for his work, but the reality he arrives at is far darker. Laid out on tables in MoMA’s gallery are examples from his “Constructed Realities” body of work, which layers written records and other material from Nigeria’s colonial period, when British occupiers used photographs to validate violent imperial practices.

Rounding out the show are around 30 prints from Logo Oluwamuyiwa’s “Monochrome Lagos” series. The candid snapshots taken around the city are full of energy, and so, it seems, are their subjects—everyone is walking, driving, or otherwise on the go. It’s through Oluwamuyiwa’s prints that we get the purest picture of Lagos, one shaped by the city’s people, streets, and buildings—not the Global North. “My hope is that one can walk out with a sense of a city center that breathes and allows artists to think in relation,” says Onabanjo. “It's still a ‘New Photography’ show, but it's giving you something that is reflective of the world. And the world is always shifting and changing.”

in your life?

in your life?