Ellsworth Kelly would have been 100 next week, and museums across the United States are celebrating. No fewer than 10 institutions, from the Museum of Modern Art in New York to the Santa Barbara Museum of Art, are staging exhibitions dedicated to the artist, who died in 2015. Over the course of his seven-decade career, Kelly created monochrome shaped canvases, drawings, and other works that made audiences think about abstraction, art history, and nature in new ways. His masterful and inventive use of color also managed to bring a fair amount of sheer delight into the world—and inspire a new generation of artists in the process. Ahead of Kelly’s centenary on May 31, we spoke to four artists—two of whom met Kelly personally, and two of whom knew him through his work—about the artist’s impact.

Lily Stockman

Do you remember the first time you encountered Ellsworth Kelly's work? Where were you, what did you see, and what did you think of it?

Mrs. Reichlin’s first grade art class. Each table in her classroom was named after a different artist, and I remember being drawn to Kelly’s simple shapes and bright colors and copying them over and over until they evolved into a horse or a house. Later in college I had a wonderful painting professor, Nancy Mitchnick, who talked about “color / shape” painting, which I associate with Kelly. I’m a color shape painter, I’m sure, in no small part because I learned to draw by copying those Kelly paintings on Mrs. Reichlin’s table for a decade of my schooling as a child.

What do you think made Ellsworth Kelly a good artist?

Drawing, drawing, drawing. He understood the world by drawing it. Always a sketchbook and pencil in hand, finding the line in the thing he was looking at. In a way he’s a lawyerly artist, and his legacy can be seen as a legislature of the natural world; he’s looking for the truth of the physical matter around him.

Has Ellsworth Kelly's work taught you anything about how to approach your own?

I had a painting professor start the year with a color theory project in which we painstakingly mixed oil paint to replicate every color in a Kelly grid on index cards. Then card by card, we mixed a warm into each color, then a cool, next some titanium white, and then finally some lamp black, ultimately making around 400 index cards each, which we organized into massive color grids on the concrete walls of the Le Corbusier building, [the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts], in Cambridge, Massachusetts. From the street, you could see these undulating colorfields flickering and pulsing through the glass walls, like Kelly’s gleeful ghost haunting the brutalist architecture and having a great time doing it. It gave me incredible respect for what a true master of color Kelly really was.

Julia Rommel

What was the first Ellsworth Kelly work you remember seeing?

Colored Panels for a Large Wall (1978) at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., which I visited as a teenager. I remember feeling excited to be in the huge atrium with the work… The panels were simple and playful, and you had to look up. It made me pay attention to the space, to the extent that I can remember it years later. I think the work eased my intimidation at entering a seemingly solemn art museum… like, Oh, this is what art can be? I want in!

What do you think made Ellsworth Kelly a good artist?

How he puts pressure on just a few crucial decisions (shape, scale, color), and his exacting preferences in those choices. His work makes me feel joyful and engages a room with a sense of play. I want to hang out in those spaces.

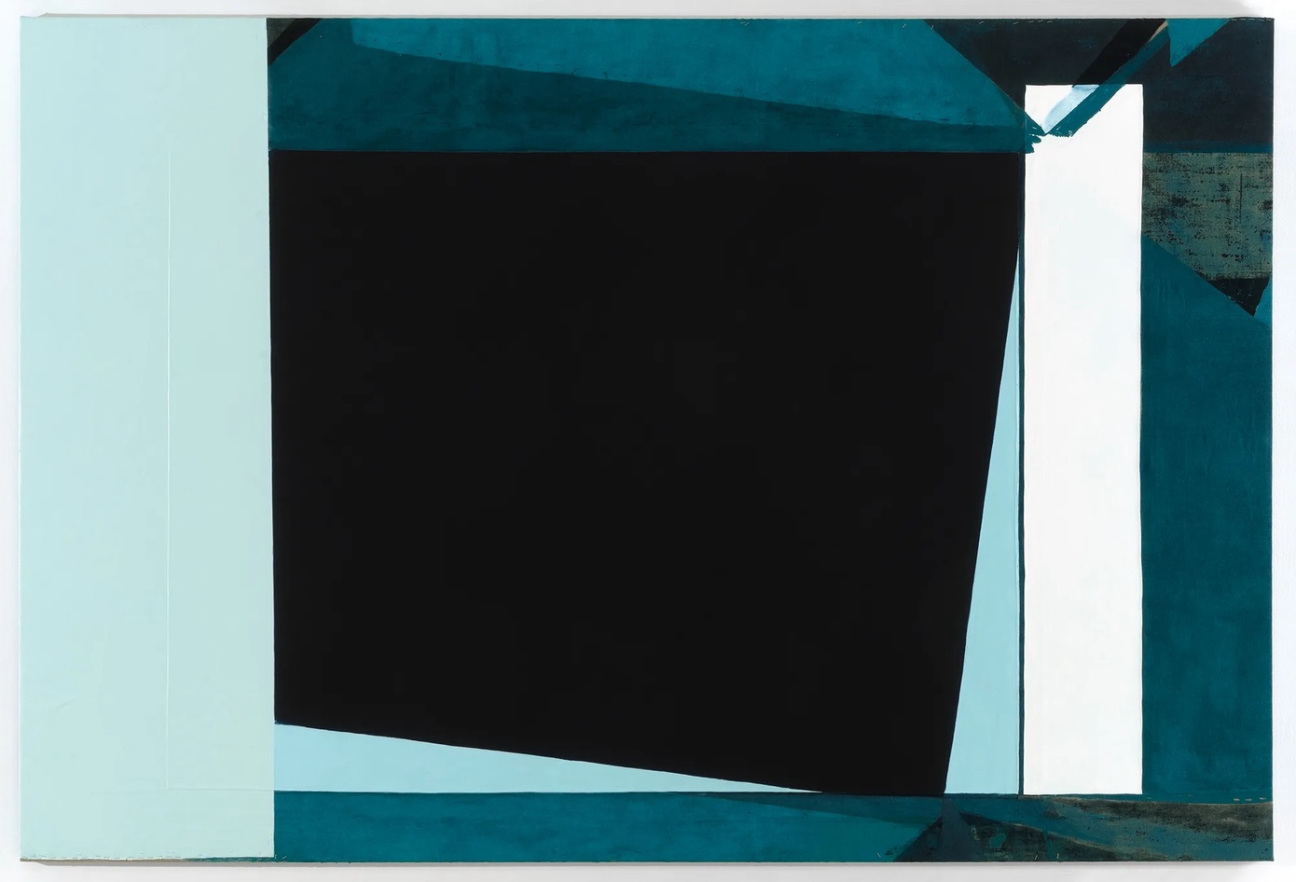

I hear you made a painting in response to one of Kelly's photographs. Can you tell us about it?

In 2016, Matthew Marks had an Ellsworth Kelly photographs show that blew me away. Not only was each photograph a stunner, but collectively the show felt like a window into Kelly’s process: what he perceived in the world that could become the origin of a minimal painting. I wanted the kind of depth and architecture in my abstract paintings that I found in his photographs, so I took a stab. Looking at Hangar Doorway, St. Barthélemy, 1977, I made The Unbelievers, 2016. The painting resolved itself more easily than most. I like to think I summoned his spirit!

Sarah Morris

Do you remember the first time you encountered Ellsworth Kelly's work?

That's an impossible question because his work is everywhere. I curated a show for Friedrich Petzel in 1999 called “Concrete Ashtray” and contacted Ellsworth to include several sculptures of his. That began a dialogue, and when I had a show with the Beyeler Foundation, he was there installing a large exterior sculpture, White Curves, 2001, in the garden. Installation week was so fantastic, talking and having lunch with Ellsworth.

How has Ellsworth Kelly's work informed the way you approach your own?

Understanding the dialogue between volume and space: Where does your eye turn to? How do you perceive space and social forms, even organic ones for that matter? Also, his interest in architecture and site-specific works of art must be mentioned. Sculpture for a Large Wall, 1956-7, which was originally made for Philadelphia’s Transportation Building, tripped my imagination when I first saw it in New York.

Did his work change anything for artists coming after him? Do you have to think differently about line or color as an artist in a post-Kelly world?

One has to interact with so many images every day that the commercial and oversaturated nature of the image has been exposed. Kelly’s stripped-down language becomes a necessity, and even a critique.

Odili Donald Odita

Do you remember the first time you encountered Ellsworth Kelly's work?

I would have first encountered it in textbooks as an undergraduate student at the Ohio State University in Columbus. There were students that were supportive of the work, and others like myself who did not understand it well enough. My mind changed for the better in the mid-1990s after discussions with other artist colleagues while my own work began to make its shift toward hard-edge abstraction.

What do you think made Ellsworth Kelly a good artist?

Ellsworth Kelly has a great sense of light, space, shape, form, and scale. One of his greatest achievements was Drawings on a Bus: Sketchbook 23 from fall 1954. While riding a bus in Paris, Kelly saw and then traced outlines of the changing shadow that trailed across his sketchbook. Afterwards, he went into his studio to fill in the spaces with inks and produced other variations of this work, which led to some of his most important paintings. His ability to open himself up to this chance experience is a great example of artistic inspiration and the opportunity it can provide to make strong and steady leaps in one’s own work.

Did his work change anything for artists coming after him? Do you have to think differently about line or color as an artist in a post-Kelly world?

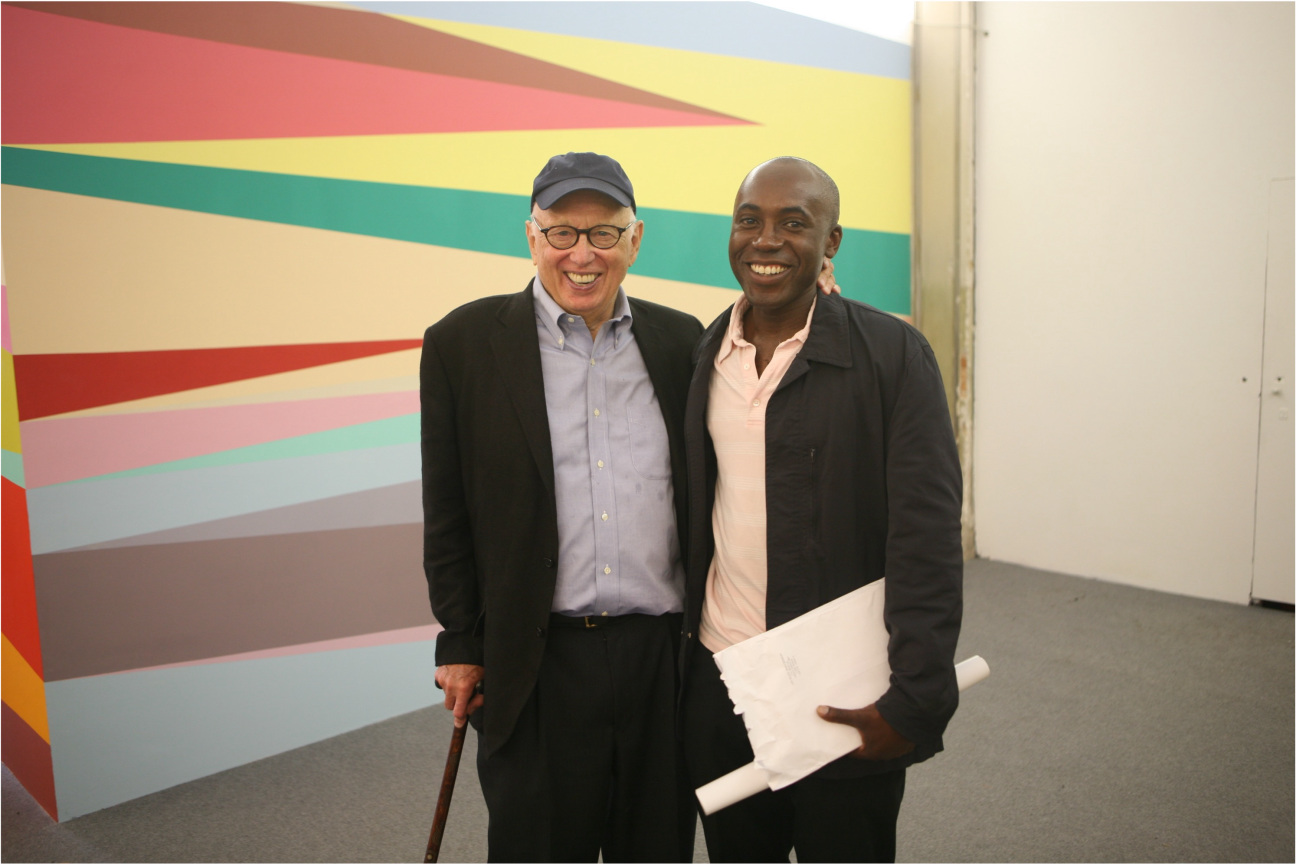

I strongly believe that Ellsworth Kelly’s work has had a profound impact on artists that have come after him. When we met each other in my installation Give Me Shelter at Robert Storr’s 2007 Venice Biennale, Ellsworth said the following to me: “My work comes before the war, and your work comes after.” There can be so many implications to this statement, but for me it is a positive statement of attitudinal shift and change in the way that color and abstraction can be perceived within a multicultural world. This meant so much coming from Ellsworth himself.

in your life?

in your life?