A chance encounter with Robert Pattinson has been known to trigger many reactions, including vampiric lust, fainting spells, and bored shrugs. For Geneva-born artist Shahryar Nashat and Houston-based writer Bruce Hainley, it provoked a different response. The actor became the fulcrum of the pair's new exhibition at the Renaissance Society in Chicago. Nashat, who has a solo show, "Raw Is the Red," on view at the Art Institute of Chicago until Sept. 11, invited Hainley to collaborate on and curate a disruptive and untitled exhibition based on the encounter. Featuring works by Puppies Puppies (Jade Guanaro Kuriki-Olivo), Karen Kilimnik, Larry Johnson, and Marie Laurencin alongside live-stream feeds and TikTok compilations, the show asks "how bodies, whether living currency or undead, circulate, distort, unalive, and, yet, love." To mark the show's opening last Friday, CULTURED called up Nashat and Hainley to talk "gore capitalism," messing with art world communication norms, and living in haunted times.

CULTURED: Let’s talk about the show’s genesis.

Shahryar Nashat: Myriam Ben Salah offered to continue a tradition that has evolved between the Renaissance Society and the Art Institute of Chicago in which artists work at both venues, something that I think Susanne Ghez and Hamza Walker had started. From the get-go, I told Myriam that I'd be super happy to do it, but that I didn’t want it to be a conventional solo show. It was an occasion to think about how exhibitions are communicated, not just made.

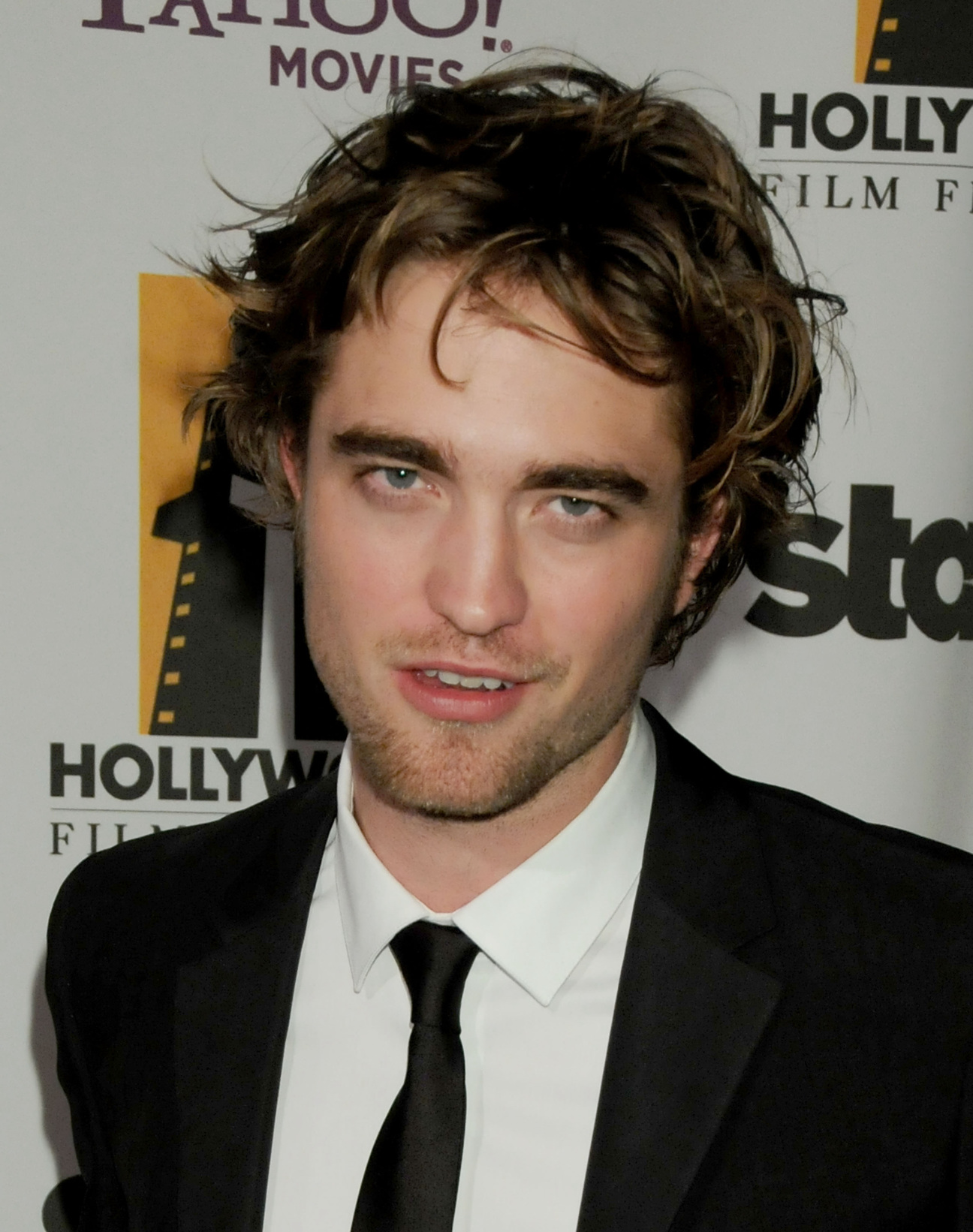

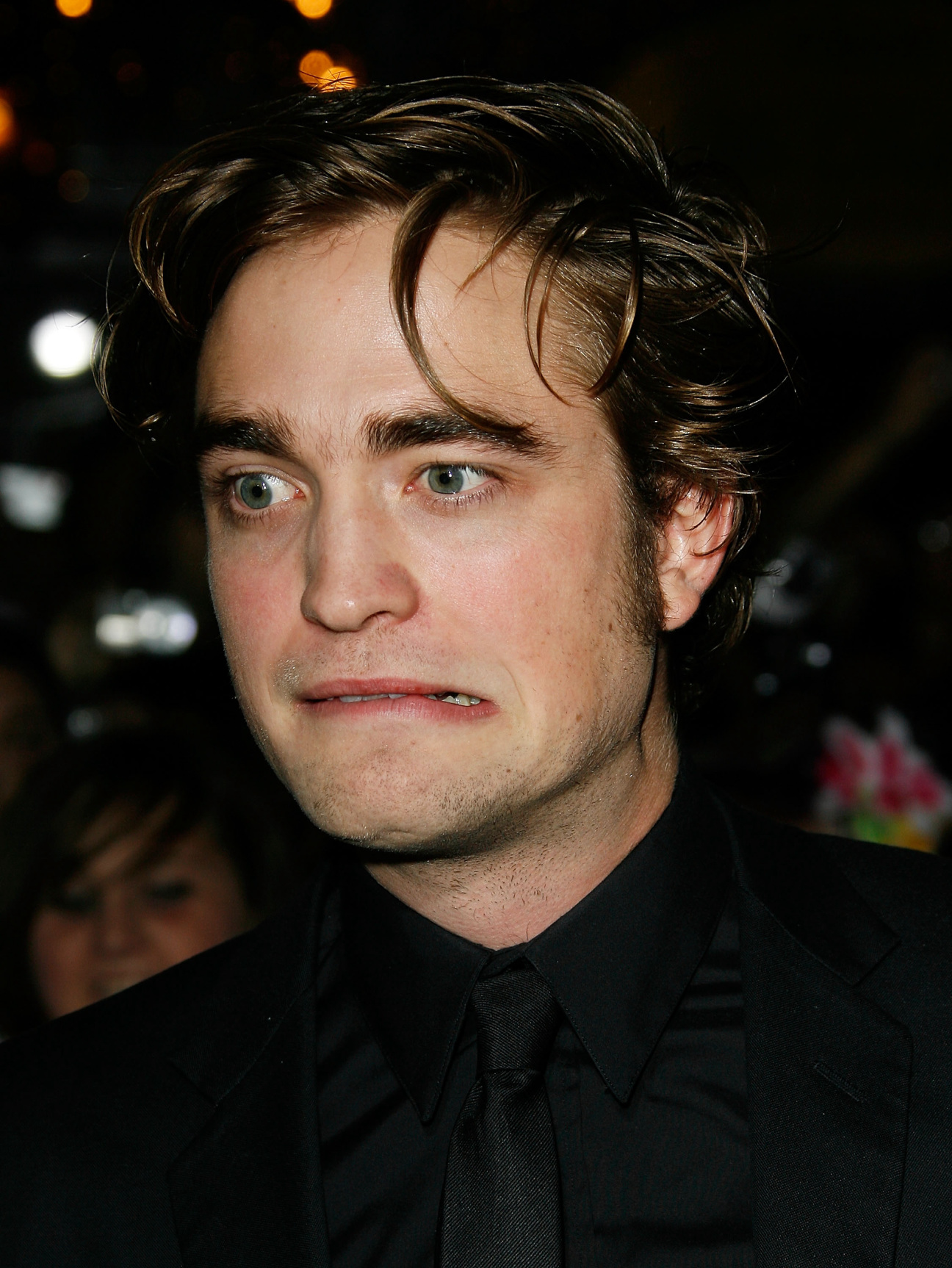

And at some point, I told her I would like to involve Bruce Hainley, but I still didn't know what it was going to be. Bruce and I had lunch in Los Angeles about a year ago. It was still a bit of the pandemic configuration of restaurants. We were in a parking lot having lunch, just talking about what it could look like to come together as friends and artists. We started talking about the idea of a muse or a mascot, and we were like, “Maybe we should find this entity or person and see how things come together under that.” By total coincidence, Robert Pattinson was having lunch at the same restaurant. I took a snapshot of him. Bruce and I looked at each other and were like, “There you go. He's here. There has to be a reason.” For a while, the show was called “Robert Pattinson.” Later, we decided to remove his name and just keep his image, which speaks for itself and more.

CULTURED: Would any celebrity have sparked that “aha” moment, or was Robert Pattinson especially compelling for you two?

Bruce Hainley: I think there are some people that it would have been fun to see having lunch, but would have made us say, “That's not our mascot.” Robert Pattinson is really a star rather than a celebrity. In terms of the [Renaissance Society] show itself, we're very interested in the undead, and bodies as living currency, and the dead as a manifestation of haunting. These are incredibly haunted times. Even when something’s over, it’s not over—politically, on the career level. The most random one recently is the new PR behind Liz Holmes, who is no longer even Elizabeth Holmes. Who does this Times-sanctioned revamping work on?

There's art in the show; there are also things that are adjacent to art, such as cultural production—the makers may or may not consider them art. We think they're interesting in the context of a conversation about bodies and pleasure, both in relation to "gore capitalism," to use Sayak Valencia's term, but also love. Pattinson's film career touches upon all of those things, but he doesn’t appear in any of the art in the exhibit.

There are mostly living, working artists in the show, but there is one artist who is not living, and that is Marie Laurencin. We're borrowing a painting from the Art Institute. We're interested in Laurencin as an artist, but also as this curious figure who has been disappeared by the museum that collected her. This painting has never been on display at the Art Institute, even though it's been in their collection for four decades. What does it mean for it to come back?

Nashat: On one end, as Bruce just mentioned, there’s Laurencin’s painting of a young woman who's no longer alive, done by an artist who's no longer alive, bought by a museum who has never shown it, and kept it in their storage for as many years as they have acquired it; on the opposite extreme, there are artworks by living artists, a collection of social media posts compiled by an artist who reappropriates them and posts them when he’s ready. There are live feeds. For example, there’s someone who streams their sleep, with the possibility of their sleep being interrupted for money with an alarm. Whoever pays can buy their sleep and their waking. You’re not just looking at “dead” things, but undead returns and things that have a direct correspondence in the world.

Hainley: In terms of a figure like Robert Pattinson, one of the images we put up fairly early [to publicize the show] was of a [Madame] Tussaud’s wax figure of him with fans running their fingers through his fake hair. When is a body like Robert Pattinson’s actually embodied? And how is it embodied for people? For so many, he lives as pure representation. There's so much emulation and desire by millions of people to be near that kind of presence, and to mimic it through their own postings and screenings. It complicates or forces us to think about what our relationship is to liveness in the first place.

CULTURED: There’s something about our ideas of reality and ownership there, too.

Nashat: There is this moment when the body of a celebrity doesn't really belong to them anymore because the ways it's used go beyond their control. When the body becomes currency, the subjectivity disappears. Almost every work or every gesture in this exhibition is dealing with a body.

Hainley: In this moment of relentless figuration circulating in the art world—as if we truly understand what a body is and how it represents and is represented—the show really wants to open up the ground of what is disfiguration, defacement, or even effacement as part of that. It’s questioning how abstract any given body is.

One of the works in the show we're excited about is a video by Larry Clark that he made in 1992. It's a direct appropriation of a talk show in which a teenage boy is talking about being raped with a broomstick by a group of similarly aged teammates who were hazing him. This work is about violence to bodies and racialized communities, and how that reconfigures thinking about the body's existence and agency, the undoing of that selfhood by violent, physicalized ignorance.

CULTURED: Can you touch on the artist as celebrity or anti-celebrity?

Nashat: There is no dogmatic way to look at it. Artists are individuals; they write their history as they're living their life. Every decision we make is going to be part of that mythmaking, whether we are totally anonymous and invisible or want to be absolutely everywhere and have access to every opportunity. You just have to be very conscious of the way you’re being read and make sure it’s the way you want to exist as an artist and as an individual.

Hainley: One could say that the advent of modernism is tied to this. [Gustave] Courbet worked the press hard… The circulation of information is so overwhelming. On some level, most have this sense of agency with social media, but we’re all being data-mined and turned into products, to sell ourselves back to ourselves.

CULTURED: How did you build the show, and how did you know where to end?

Hainley: We worked almost brick by brick. After the encounter with Pattinson, one of the first artists we were really working through was Laurencin… Then it was like, “OK, how do you respond to that painting?” The show really proceeded one step after another, reaching some kind of intensity or fascination or resonance, let’s hope.

Nashat: People are so used to getting a show title, a press release, a list of names, or a description that they probably don't ever read. It corresponds to the mode in which art is being made and communicated. As soon as you don't conform to the ways information is usually circulated for reasons that just feel natural, you create mystery, but our intention is not to be mysterious. We want to let the things that matter come first–that’s what’s in the show. You have to be in the space, and then the thinking arranges around it.

Hainley: There are extreme forms of violence suggested in the show. You couldn't have a show about the undead and the many roles of Robert Pattinson without including violence, but it is also a show about love. A love of art, of life, of living bodies, bodies that can actually survive.

This exhibition will be on view from May 13 through July 2, 2023 at the Renaissance Society at the University of Chicago.