As Wangechi Mutu Zooms with me from her sunset-lit Nairobi studio, her team in New York, where it’s still morning, is at work preparing for the Kenyan-American artist’s upcoming show at the New Museum. One aide makes wrinkles in Mutu’s sculptural fabrics; another gouges gallery walls with what the artist calls “wall wounds.” In a matter of days, she will join these friends, some of whom have come back to work with her after 20 years, for a gathering she describes as a family reunion. (“I’m super psyched!” she says, and tells me she has pictures from decades ago to show how they’ve all aged.) The family reunion metaphor might also apply to her works themselves—as we speak, Mutu’s paintings, collages, videos, and sculptures are traveling from across the world to convene in the museum in advance of the show’s Mar. 2 opening, and make themselves at home. Mutu’s bronze fountain sculpture of two tree-like voyagers, In Two Canoe, 2022, will greet visitors in the lobby; her bronze female-reptile fusion, Crocodylus, 2020—transported like a queen by eight men who hung the sculpture from a rig to fit it into the elevator—will occupy 13 feet of floor space in an upstairs gallery.

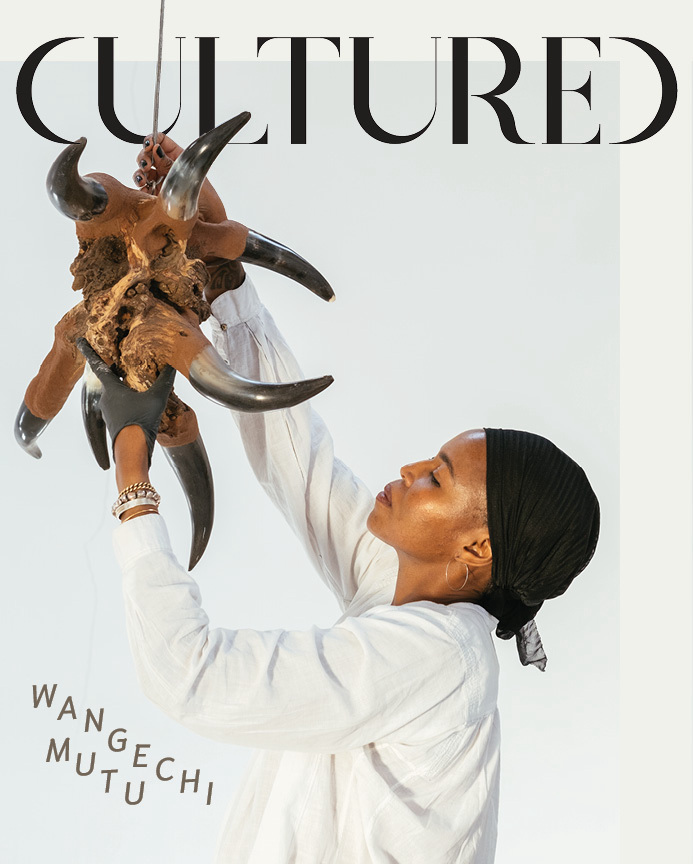

Mutu, 50, became known in the early 2000s for her lavish collage admixtures of the mythic and mundane: pinup models with crocodile tails, women grinning at the viewer as if unaware of their bleeding severed limbs. Some of these women—squatting and posing with reptiles—were power figures, “Otherworldly superhero beings,” she calls them, “That could redeem us from our bullshit and our small-minded problems that hurt us so tremendously.” In the intervening decades, her works grew larger in scale, more complex and layered, but no less potent or disturbing. On the walls, her aesthetic of aggregation and accretion throbs with pent-up energy; her newer sculptural work, likewise grounded in gathering and agglomeration, feels calmer and more elemental. She makes her clay from soil in Nairobi, which she bakes in the sun, and adorns her sculptures with natural materials she has gathered from the land: moth wings, quartz, driftwood, bleached skeletons of sea animals. Her sculptures seem less confrontational than her earlier works, more assured of their place in the world.

Growing up in Kenya, Mutu drew constantly. She knew she was an artist, but in a newly independent country, such a life seemed impractical. She left Nairobi in 1991 to attend high school in Wales, then art school at the Cooper Union—sleeping in the hallway of her Brooklyn apartment so she could use it as a studio—and then grad school at Yale. Mutu achieved international acclaim while stuck in the U.S. during her 12-year bid for citizenship. When she finally secured it in 2015, she divided her life between New York and Nairobi. Her first retrospective, titled “A Fantastic Journey” at the Brooklyn Museum in 2013, mythologized Mutu’s own story of leaving home to become herself. “Intertwined,” the New Museum survey (curated by Vivian Crockett, Margot Norton, and Ian Wallace), traces the connections—in terms of place as well as aesthetics—in Mutu’s practice over decades.

There are creative genealogies visible across the works of the Mutu's new show. Maria, 1997, an early sculpture in which a figurine of the Virgin Mary is topped by a cracked baby doll’s head with cowrie shells for eyes, appears to beget a later collage in which a nude, male torso is topped by a pearly helmet with inlaid mechanical eyes (part of her “Family Tree” series, 2012). The drawing Wing Tree Birthing, 2011, in which a woman with bike wheels for feet sprouts a tree from her body, seems to anticipate Mutu’s The Storm, 2012, in which a massive figure—her flesh covered in fishnet, her back arched against a clay-pink sky—births a tempest of tangled black hair. The heroines of her mid-2000s collages—their bodies mottled with disease or decorative camouflage—come to life in the animated video The End of eating Everything, 2013, and take on yet another in The Glider, 2021, a soil and charcoal sculpture of a serpent goddess with perfectly scooped-out circles for scales.

While Mutu’s work is often discussed in terms of gendered violence and colonialism, her conceptual scale tilts beyond modern history and toward millennia—an expansive perspective from which, she says, “our tribalisms completely dissolve.” She describes her gathering practice as a form of communing with the earth: “To be drawn to these materials, to be able to recognize their beauty, that is my prayer.” It is difficult to make work that honors this natural bounty, she says—but with the bronze avatars she created on commission for the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Fifth Avenue facade, she managed to “genuflect” to it: their head discs reflected the sun, illuminating the building and the street below it. Mutu has said that these figures, collectively titled “The NewOnes will free us,” 2019, evoke the “stillness that comes from knowing that you are supposed to be here.” They also signal her own hard-earned status as an African woman artist who has made a home for herself at one of the world’s most hallowed museums. And yet, lest we see these works as an arrival or culmination, the curators of “Intertwined” positioned one of the sculptures in a small nook apart from the rest, where viewers might encounter it "like a surprise,” Crockett says, rather than as a grand monument to Mutu’s achievement. The piece is not demoted, but rather bound together with the other works on view—one more miracle, or wink, among many still to come.

"Intertwined" is on view through June 4, 2023 at the New Museum in New York.

in your life?

in your life?