Firelei Báez had just given a talk at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts when I called her from Miami. Art Basel Miami Beach was winding down, and the crowds of out-of-town revelers were beginning to thin out.

The 20-year-old art fair’s party circuit is legendary, but it’s only possible thanks to the vibrant arts and nightlife scenes that course through Miami year-round—something that Báez, a native of the Dominican Republic who grew up in the city, knows well. "It's hard to say that to a lot of people, especially when they're in Miami having a good time," she laughs, referring to the throngs who come from far and wide to partake in Miami’s Art Week festivities.

Such implicit social dynamics—embodied, for example, in the divide between the city’s locals and the out-of-towners who take the metropolis by storm for a week every year—feed into the conceptual framework of "Americananana," Báez’s latest solo exhibition at James Cohan in New York. When asked about the inspiration for her show’s multisyllabic title, Báez intones, "Na na na na, hey, hey, goodbye," quoting the chorus of Steam’s 1969 track of a similar name. It’s also a reference to a 2010 show dubbed "Americanana" (shorter by one "na") curated by art historian Katy Siegel at Hunter College, where Báez was then a student. “After the economic loss of 2008, they were questioning this nostalgia for a fictional past," Báez recalls, describing the overall effect as a "kind of blurring of Americana.” For the artist, the 2010 show resonated with a feeling akin to saudade, a Brazilian term that refers to "hav[ing] this strong emotion for a thing that might have never existed." As she mentions this, the vague but piercing melancholy of Steam’s iconic refrain indeed comes to mind.

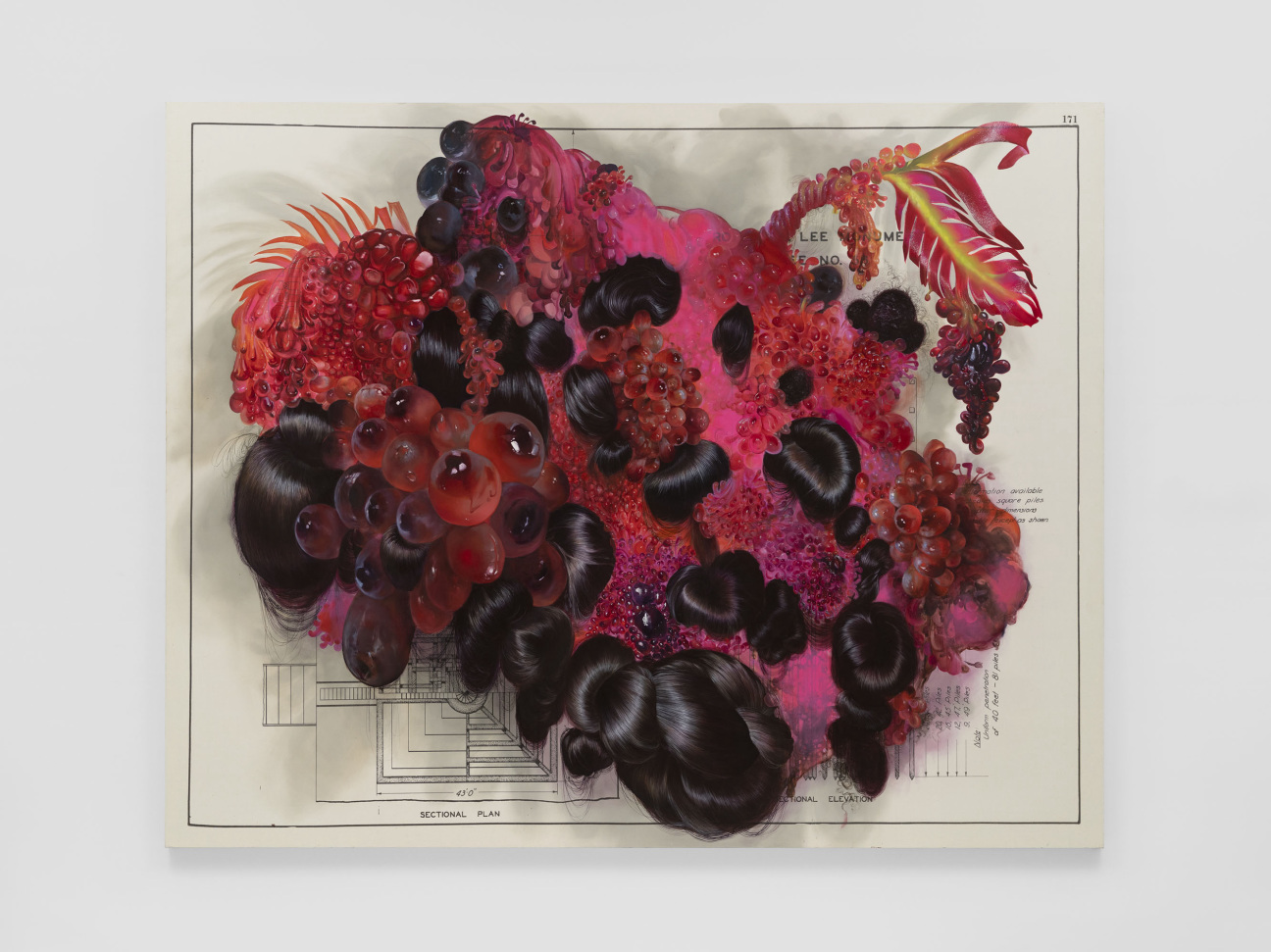

In "Americananana" Báez debuts a series of eleven oil-and-acrylic paintings that center semi-abstracted organic forms—ranging from illustrations of weather patterns and microorganisms to allusive portrayals of mythical characters—layered over reproductions of historical maps and diagrams that are printed onto the canvases (though one in fact uses a neoclassical portrait of an unnamed Black woman made in 1800 to reimagine her likeness in divine, out-of-body splendor). The finished compositions successfully obscure the original documents, thwarting any lingering functional value. "The groundwork for me…interfering or reacting to all of [these documents] is the presumption that they’re fiction," says Báez of the archival material. She considers their content "as much a projection of desire" as a schematic reflection of past realities. In other words, "They’re factual, but not truthful."

Centered on a bulbous mass of grape-like shapes, Fruta Fina, Fruta Estrańa takes as its subject the cells of Henrietta Lacks—whose ovarian cancer tissue samples, taken without her knowledge, engendered an immortal lineage of cells that were crucial to decades of medical discoveries. The painting features celestial, richly colored orbs-as-cell clusters, rendered with a naturalistic elegance reminiscent of a 17th-century Dutch still life, while dark locks of hair and various flora suggest a more sci-fi-aligned vision. The imagery sprawls across a 1937 architectural proposal for a Depression-era infrastructure project. At the time, Lacks—unaware of the future fate of her own body tissues—was the teen mother who would soon give birth to her second child.

As a Dominican in the U.S., Báez grew up surrounded by sociopolitical norms that left her with the sense that, as she puts it, "I didn't have a history." The painter cites the writings of Puerto Rican immigrant and Harlem Renaissance-era thinker Arturo Alfonso Schomburg as a key influence in learning otherwise. "Not only is my history here, it's…almost foundational to a lot of Western history," she says.

This enhanced perspective grounds Báez’s work today. "I think of the Caribbean almost as a laboratory for everything that happened,” she says. "It’s where populations were eradicated and migrated in and out." She also explores the pernicious Western tendency to fetishize and exoticize Caribbean peoples, a centuries-long phenomenon that, for Báez, manifests as everything from narrative tropes in Shakespeare’s The Tempest to blatant modern-day sex tourism. Much of Báez’s practice is grounded by the questions she asks herself constantly: "What is the archetype? What is this continuing fantasy?"

Instead of seeking easy answers, Báez opts to dig deeper into the queries themselves. In her painting Olamina (How do we learn to love each other while we are embattled), Báez focuses the work on Lauren Olamina, the Black teenage protagonist of Octavia Butler’s sci-fi epic Parable of the Sower. For Báez, the novel holds a particular resonance—it's about a woman adrift in "a world [that] has ecologically and politically collapsed around her." In the artist’s words, Butler offers guidance for how to “remain whole outside of a system that is intent on destroying you." Below the painting is a print of Elwin J. Woodward’s “Story of the Ages From Creation to Redemption,” a morally fraught timeline of the origins of sin, made in 1912 which lays out the ominous details of "God’s Plan of Salvation for Lawbreakers." But Olamina’s lace-trimmed silhouette obscures the document, reaching languidly across the canvas in an act of easy defiance.

While themes of resistance, heritage, gender, and agency loom large across the works in "Americananana," Báez refuses to reduce this body of work to a thesis—preferring to interrogate the as-yet-unanswered questions it raises. “What is the friction created by the projection of desire? What are the responses? What is the gaze that looks back?"

“Firelei Báez: Americananana” is on view at James Cohan at 48 Walker Street in New York City through December 21, 2022.

in your life?

in your life?