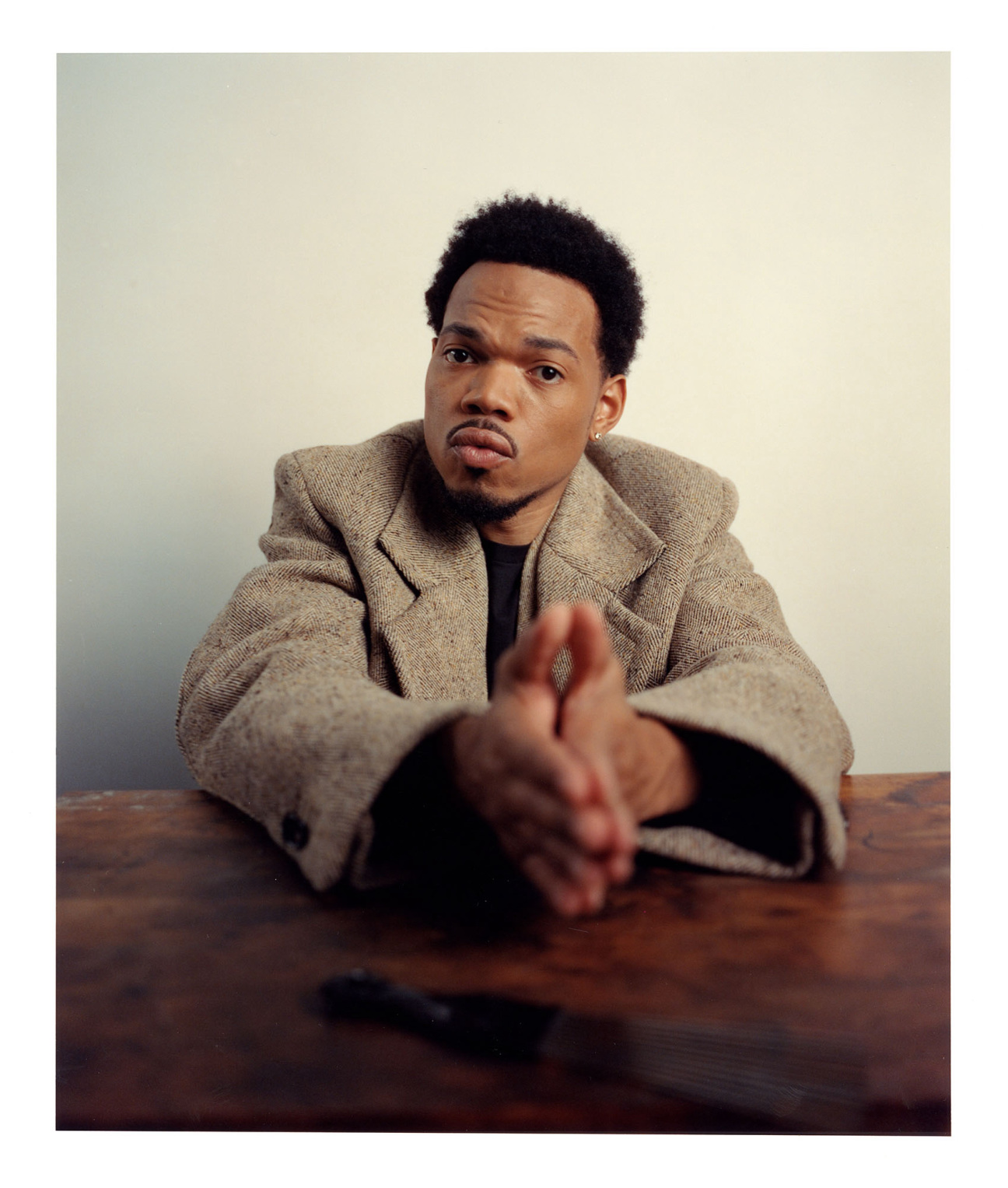

THEASTER GATES: If we could go back a little, Chance, I want to hear you talk about your progressions, because it would be unfair to just start at, “Well, I was making these songs, and I want them to be in a museum.”

CHANCE THE RAPPER: Coming from the written word, I was never talented in the visual arts. I can’t even draw a straight line. I always respected what I saw, but I couldn’t create anything beautiful or fully understand the ins and outs of it. The first time I really got to see the impact of visual art was when I made [the mixtape] 10 Day, because of the cover art created by Brandon Breaux, whom I know you work with. It’s crazy how many connections you and I have, by the way. Brandon turned photographs that Nolis Anderson took into these visceral digital paintings. People responded to them before they could even get to the music.

The museum thing now is two parts. First, I want to stamp the moment of what it feels like to release art. As artists, we have visions or ideals that we put into our pieces, but we don’t always necessarily share them. When we do—when we decide to document them or to publish them or to put them into the world—it feels like a big moment for mankind…for existence. Giving art the space to live, and to be able to be in the presence of the artist and the audience at that initial moment, is radical, almost liberating. Secondly, when you see art in museums, the pieces are typically on loan from a collector or gallery. All the artists own the pieces for all the work I display. It’s important because a lot of people aren’t regularly exhibited artists and some artists die before their work gets displayed in a museum.

TG: This here is your admission to being committed to a set of artists that are not totally discovered by the constituencies of the art world; folks who are still emerging in their practice. To be able to give them this platform is a beautiful collaboration, gift, and outcome.

CTR: I’m trying to document where Blackness is in 2022 and 2023 as it pertains to being on the precipice of revolution, and how that feels for all these people from around the world. I’m from Chicago, Yannis [Davy Guibinga] is from Gabon, and Joey [Bada$$] is from New York; having all these different expressions around the same idea gives the true and clear experience of what we deem it to be.

TG: I think of you going from Chicago to the Venice Biennale in your video for “The Highs & The Lows.” You got your crew. Y’all got these frames. You’re showing everyday Black life in Venice—artful Black life—and using the medium of film to reposition yourself as a musician. It’s not just about rap, rhyme, or language. You’re framing Venice so that the person that might feel completely foreign to the art world can be like, “No, nigga, I’m in the frame. My boy Vic is in the frame. Thelonious is in the frame. We’re in the frame.” These moves that you’re making are at the edge of a contemporary moment where the music world doesn’t know what the fuck to do with it and neither does the art world. You got the Kehinde Wiley puffer on, and you’re moving from what historically had been a silo into a new world.

CTR: This revolution that’s happening is not dependent on any single person like me. It’s on the people. We’re all tapping into it and coming into it at the perfect time.

TG: In this moment, there are some important brothers and sisters behind the camera: Kahlil Joseph, Bradford Young, Ava DuVernay. Cinematography allows so much possibility for music because you’re able to extend your words onto this visual platform and add so much more dimensionality. I’m thinking about “A Bar About a Bar,” which, for me, is a hit. Like, you got church hits, you got conceptual hits, and you got hip-hop hits. But, “A Bar About a Bar,” that’s my shit. Because it’s…nothing. And in that nothingness, you get to lay with a world that’s non-linear.

CTR: I’ve been trying to get back to that freedom where I create art because I am an artist, not just because I have a story to tell. Not just because I believe in a certain idea. Not just because I need to make money. The first idea that I had [for the music video] was to just have singular text on a screen with black negative space and have my words be the focal point. Being allowed to be playful with my words is the best that I will always be. The freedom to be able to do that is why artists like being artists.

TG: I’ve never had a conversation with my gallery about losing a market because of what I made, but I suppose it must be different for musicians. Do you do what’s expected by the public or the producer? Or are there other things that we need as artists? “A Bar About a Bar” feels like you’re in partnership with artist Nikko Washington; there’s some more meat on these bones. But I also think music should allow for honesty from its artists, like “This album is gibberish,” or “I’m not the revolutionary on this album,” or “This is my booty album. It’s to my girl at two in the morning.”

CTR: That’s the issue with being an entertainer: when you’re symbolic, you become commodified. People need you for a specific reason and stepping outside of that can cause dissonance. Celebrities are put into these frozen images of themselves that people identify with—which is great—but then they become tied to them. Great artists are always themselves. You have to remember that the audience isn’t one specific person. At the end of the day, you still have to create, and you still have to share. That is our gift.

TG: I love the fact that you’re this Black bridge—this diasporic bridge—from Chicago to the Continent to the Caribbean—with Black Star Line Festival. This idea of a gathering is something that I believe in deeply, and it feels very close to Black Artists Retreat.

CTR: I played Johannesburg in 2018, but I was in and out. It’s not typical to send American artists to play shows on the Continent, and that’s by design. My first time going to West Africa was this year. Vic [Mensa] and I were having a conversation in Ghana about all the misconceptions of the area and how loving and inviting it was, especially in Accra. That’s really when I started working on the festival. There ended up being so much more love and curiosity than I would have expected. Everyone wanted to help. It was eye-opening to see how many of us have just been waiting on the opportunity.

TG: Ghana is where I would go if I ever wanted to see the love of Black people…or even the origin of love. Ghanaians have it in their eyes and in their voice. I don’t ever want to seem like ignorantly generalizing people, but there is kindness, man.

CTR: Ghana’s first president founded the country on global Blackness, Pan-Africanism, and free Africa. It’s been in the fabrics of our history. What’s crazy is that I didn’t go out there with the expectation of having any historical lineage or connections, but it turns out that my great-great-grandfather was a Garveyist and my great-grandmother grew up very close to the Church. I also found out a lot of Black people have been going to Accra since the ‘20s. Walking through the streets there, I’d run into people from 187th Street, Inglewood, California, wherever in Chicago.

TG: Like you said, it’s always been there, and we’ve been going back. But I do think that through your personhood and music, you’ve been able to bring this idea to the next generation of young people. I think about my boy Tremaine Emory and Supreme; fashion is another route to travel ideas.

CTR: Growing up I was never big into fashion, but this experience really made me realize how much it is a part of art and design. I saw how much time goes into sketching, sourcing material, and telling stories with pieces, but also how hard it is to realize these ideas as a Black person. The other side is the idea of commercialization. How radical is it that Kehinde even did that jacket? In the art world you rely on a gallery to find you the best collector to give you the best price. A lot of times power or autonomy comes from commercialization and from making things more accessible. So Kehinde’s jacket sparked a deeper conversation for me: what does it mean to be the owner of the IP of a work beyond that singular first piece that you make?

TG: I built a band called the Black Monks of Mississippi as a vehicle to meditate on the history of slave spirituals and gospel music. There are moments when I hear your voice and it feels like you’re intentionally channeling a young Chancellor.

CTR: Speaking on faith is very radical in this time—as well as throughout history—and the music that says it with the most fervor has always been gospel. Lately, I’ve been loving music the way that I loved it when I was 14. It comes out in performances and even in the recordings. I’ve gone back to basics.

TG: It’s beautiful to see that. I don’t know what to call it, but I feel like there’s room for a new kind of performance genre. If you look at David Bowie, Def Leppard, or Metallica—you know, the white boys—they dressed up. Then you look at Earth, Wind & Fire, and The Spinners. They were fly, too. All of that was performance, fashion, and music. I think that you’re in a place where you’re starting to push those boundaries even more.

CTR: I’m trying to give what I have in the moment, and not be so hesitant about things, because I’ve been on the extremes of both ends—just going, going, going or too strategic. I’m trying to find the middle ground. Part of that comes from recognizing my community is so much larger than what I thought it was. From what I’ve heard, photographers still struggle to be recognized in the same art space as sculptors and painters, but you gave us the platform to tell our stories. That’s the community I at some point hope to get to, you know; to be able to put people in that situation, too.

TG: I’m telling you, Chance, you’re already there. Thank you for being such an amazing ambassador to the spoken word, to the tonal word, to the rhythmic and metronomic word. In all these ways you’ve been able to evolve one’s personal, creative journey into a lifestyle befitting of a world-class artist.

CULTURED's Winter 2022 issue is now available.

in your life?

in your life?