I am worried I won’t like Lari Pittman’s paintings. I remember clicking through them during the Los Angeles-based artist’s Hammer retrospective in 2019 and thinking they were messy and colorful, but not in the way I like. Pittman’s palettes are typically acrid and bombastic, like a person dressing for attention—greens next to purples, things like that. And the compositions are always packed full, offering limited real estate for the eye to rest. Perhaps worst of all is Pittman’s tendency to embed words in his paintings, which I can easily get snagged on, snob that I am. All of these first impressions come flooding back as a light cold sweat when I reach the third floor landing of the Museo Jumex in Mexico City, where Pittman’s new monographic exhibition, “Lo que se ve, se pregunta,” lies waiting for me.

Here:

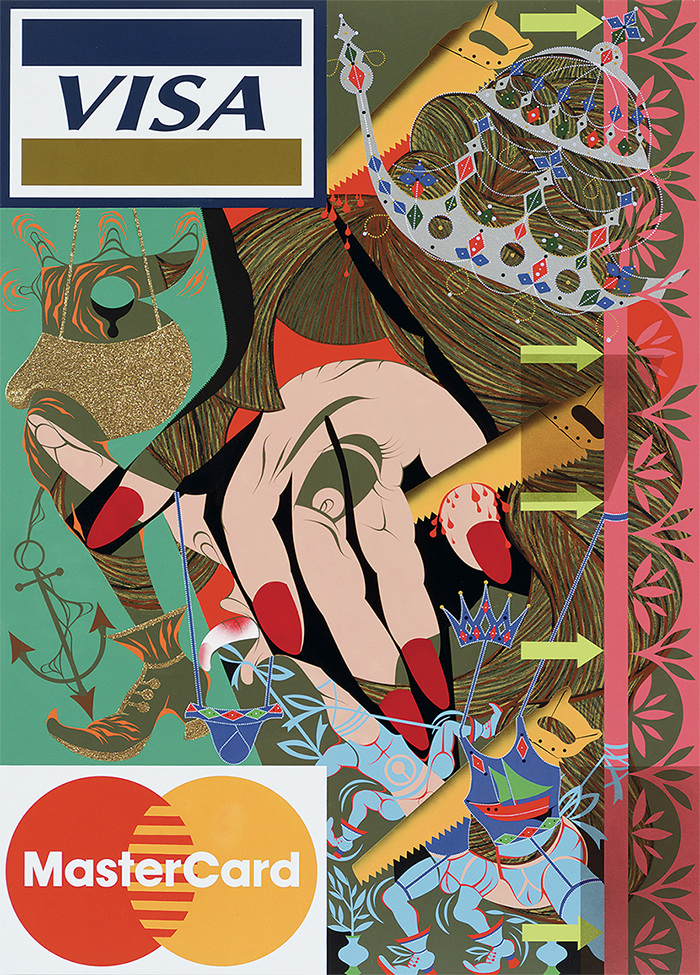

Lari Pittman, Untitled #16 (A Decorated Chronology of Insistence and Resignation), 1993. All images courtesy of the artist.

With my defenses on high, I summon my rubric for such occasions—the one I rely on to help me navigate painting, a medium that always trips me up. My rule is that if I can remove an element from the piece, then something went wrong. If I can’t, then its quality is undeniable—even if I am annoyed by it. I felt sure that Pittman’s paintings, which are so filled with marks, would be easy to pick apart, but much to my delight, Pittman blows the doors off my biases about color and content and I fall madly for the networks of small, fibrous strokes that hold his vibrating images of mastercards and severed fingers in place. Like a spider web, each mark is essential to the architecture, like a strand in a spider web. And that’s when the rabbit hole really opens up, and I discover a missing link I didn’t even know was lost, a bridge that connects movements that I don't necessarily vibe with aesthetically like Pattern and Decoration to the ones that I really do like, such as the Pictures Generation photography.

Later on, as I sit with Pittman in the marbled bowels of the David Chipperfield designed museum, I ask about his relationship to the tectonic narratives that he’s been slotted into for the sake of group show logic over the years (I.e. artists of the AIDS generation), and to the ones that I see him foreshadowing (I.e. the pre-Internet genius of painters like Laura Owens and Jacqueline Humphries). He laughs, describing the Pattern and Decoration godmothers Miriam Schapiro and Elizabeth Murray as his mentors, and his relationship to the Pictures Generation painters like David Salle as one of kissing cousins. “When I was at CalArts, I usually would sit at the table where all the students who had just come out of the feminist program were. I would just circle, like a planet, around their revisionist historical discourse asking questions like, ‘If we look at the modernist timeline closely, where are the cracks and who's in them?’” the artist recalls. “Through those conversations, I discovered I was inside one of those cracks all along. And I could see it then because I could see who my ancestors were. And I thought, whoa, what a great time to make a painting when no one else is interested.” This crime of opportunity in today’s painting-dominant atmosphere feels almost alien but it also explains why Pittman has never been retired to the canon of yesterday. Instead, his work has remained steadily in the discourse, albeit on the periphery. “Thank God there's never been consensus about my work,” Pittman cackles, “Because that might have killed it.”

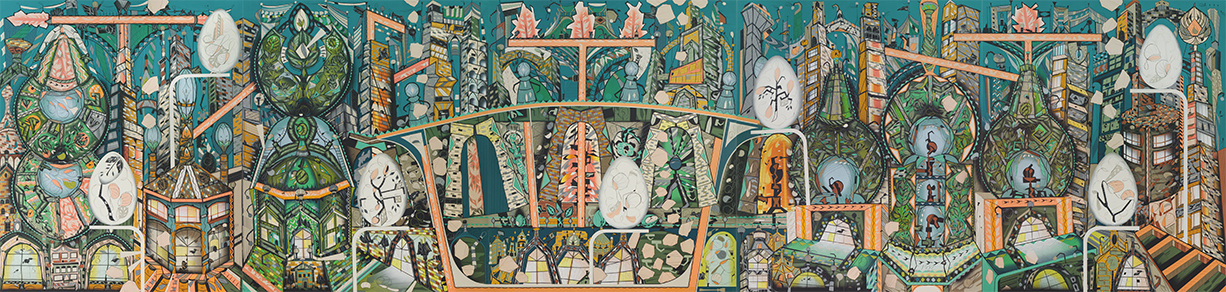

Longevity is a secret sauce, a whole recipe Pittman has mastered. It shows in “Lo que se ve, se pregunta,” which spans four decades of the artist’s work, up to its wettest canvas, Sparkling City With Egg Monuments (2022), a landscape that envisions a matriarchal city sparkling in the twilight air. “I really love big cities, they are the places of the best and deepest humanity. They are complicated, and when you’re in them, you're called upon to negotiate everyone's reality and I'm always excited by that,” Pittman says of the piece. “But I also wanted to re-gender the city because there's this historical conceit that cities are the byproducts of banking and law and real estate, all these fundamentally male heteronormative activities—so what would [a matriarchal city] look like? All my paintings are a form of conjecture.”

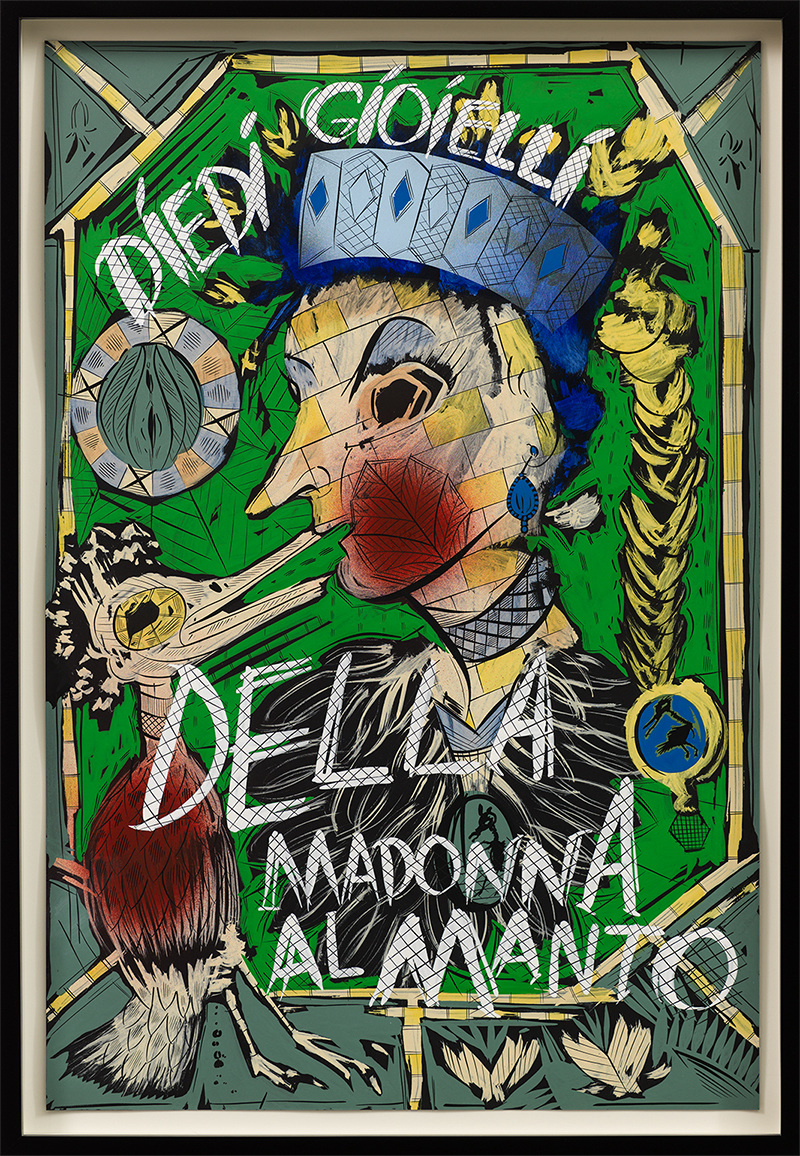

Throughout the exhibition, Pittman’s conjectures build on one another to form a prescient image of today that is as honest about today’s beauty as it is with its horrors. Pittman’s vocabulary is one of cyclical symbols: light bulbs, nooses, pomegranates, and eggs. It is a visual language that prophesizes the paralysis of the social media spirals and the oversaturation of the information age, in which all manner of content no longer tethered to its home base collides violently without a sense of hierarchy (for better and worse). Without Pittman’s conjectures, it’s hard to imagine artists like Laura Owens and Josh Smith finding their way to painterly auto-fiction. But more importantly, it’s hard to imagine a world as accurately bittersweet as the one found in Pittman’s work, where the joyous and the macabre share the same bed. Pittman chalks this up to his mother’s Colombian roots. “There's something about Latin culture that invests in the poetic register of the bittersweet,” Pittman says. “In the show, you see it as this mixture of real optimism and undeniable melancholia, because, for me, they're not mutually exclusive states of being. They're simultaneous.”

With marigolds and Day of the Dead skulls still festooning nearby shops and restaurants, one can see the overlap between Pittman’s sensibility and that of Mexico City. Though Pittman keeps a little apartment here and has been coming for decades, “Lo que se ve, se pregunta” is his first show in the country. And how do you construct an exhibition for a city that has inspired you since the beginning? You make it a valentine. Or at least, that’s what Pittman, and co-curators Connie Butler and Kit Hammond seem to have done with this monograph presentation. The show makes a point of teasing out Pittman’s affection for Mexican culture by centering works that play off typologies like large pictoral murals or santos, the saintly painted icons that one finds in the city’s every nook. These connections, like the fragile strokes Pittman uses to tie his compositions together, form their own kind of superstructure that allows for visitors to design their own adventure. “So much right now is about cataloging experience, but that seems so passive,” Pittman observes. "For me, the show will be successful if the viewer can actually be involved in the construction, rather than just receiving it.” “Lo que se ve, se pregunta” is a valentine that conveys its love ferociously, without asking the city to say it back. And what could be more generous than that?

Lari Pittman's "Lo que se ve, se pregunta" is on view through February 26, 2023 at Museo Jumex in Mexico City.

in your life?

in your life?