When I ask John Waters why it has taken him until this late in history for him to write and publish his first novel, he replies: “Well, there were 16 feature films in there.” There have also been several nonfiction books. (Though he admits “nonfiction” might not be an entirely accurate way to describe his 2014 memoir Carsick: John Waters Hitchhikes Across America). So indeed the first surprise about Liarmouth: A Feel-Bad Romance is that it is a “debut novel,” as publishing marketing speak would have it, itself. But the real eye-openers in Liarmouth, an uproarious and unrelenting exercise in enchanted invention and shameless perversion, lie on every page. One wishes there were already a portmanteau handy to describe it—“perversion” doesn’t quite work.

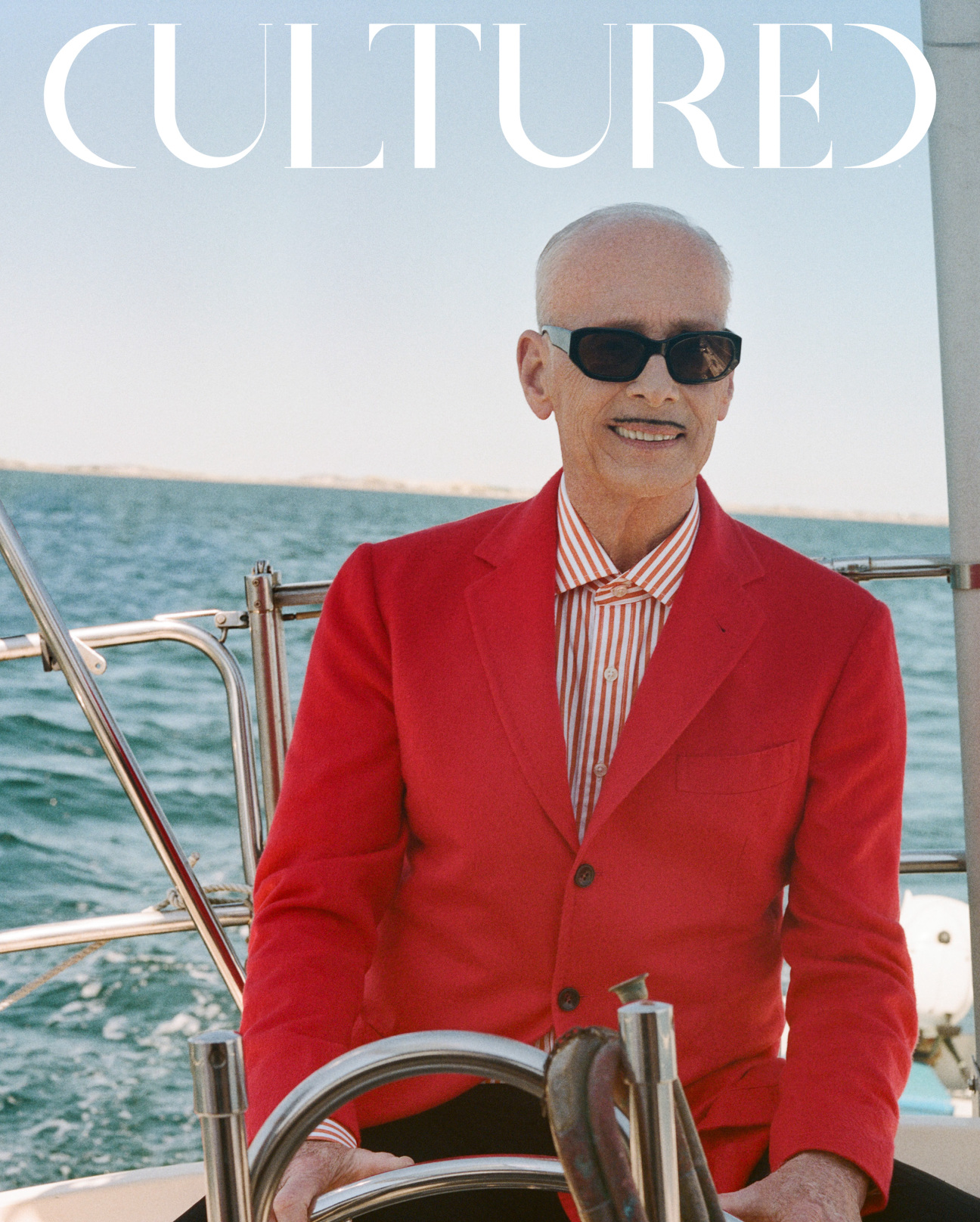

At the age of 76, Waters resides beyond the forces of the market and our current ideas about what counts as classy or important. He is an institution, his films are canonical, and it’s an understatement to say that his work has changed American culture and expanded the spectrum of modern taste. He says that he now attends screenings of Pink Flamingos with audiences filled with young people who were first shown the film by their parents. With Divine’s climactic consumption of dog feces to the tune of “(How Much Is) That Doggie in the Window?” to Cookie Mueller fucking a chicken, the 1972 film was once banned in several countries and rated NC-17 upon its rerelease in 1997. Now it’s been enshrined by the Library of Congress and the Criterion Collection.

The resistance his work used to encounter (all that banning and moaning) and his underground beginnings—putting on screenings of his films in Baltimore bingo halls and recruiting amateur actors from his local fan base—might be why, when asked about the difference between writing a novel and making a film, Waters refers not so much to the manner or form of creation (do novels allow you to imagine the unfilmable?) but to matters of reception, specifically the risk of censorship. Today there is the specter of the sensitivity reader, the bugaboo of writers everywhere that has emerged within the publishing industry over the past decade to say tsk, tsk to unpublished works and prevent them from offending the masses. But to Waters’s surprise, when his publisher sent Liarmouth to a sensitivity reader, they simply never heard back.

The same might not be said for insensitive or nonsensitive readers of Liarmouth. Though many of its characters are mean—even vicious, murderous—its presiding spirit is the opposite of mean-spirited. Marsha Sprinkle, its titular heroine, is a kleptomaniac and a pathological liar. She’s a petty thief, and is easily the most cinematic of the novel’s characters; beautiful, glamorous, malignant to a point, and given to adopting quick new disguises. After one of her heists is caught on a surveillance camera at the Baltimore airport, a nationwide womanhunt ensues. Marsha flees up the Eastern Seaboard, bound for Provincetown, where she hopes to murder her estranged husband and the father of her child.

That child is named Poppy, and she is the leader of a militant group of trampoline enthusiasts. These characters (two of them are called Vaulta and Leepa) are addicted to bouncing up and down, which happens a lot within the confines of buses and trains to either the annoyance or sudden liberation of fellow passengers. Along the way, there is Marsha’s sometime accomplice, Daryl, a rabid heterosexual cursed with a dick named Richard that has a gay mind of its own. Richard is constantly poking out of Daryl’s pants looking for action that the man upstairs would rather avoid. Talk about gay panic.

The product of Waters’s supreme visual imagination, Liarmouth is a work for the page that tests the limits of the novel form. The narration is omniscient and relentlessly roaming. This is not much done lately in the precincts of upmarket fiction, where points of view and their contours are doggedly patrolled by editors and critics. When I ask Waters, who has a book collection in the five figures, the dull but obligatory question of his literary influences, he cites Jane Bowles’s Two Serious Ladies as his favorite American novel. He also admits nonsurprise to the comparisons Liarmouth has received to Terry Southern’s practical joker picaresque The Magic Christian, though he said he hadn’t read it since the 1960s. At least somebody writes them like they used to.

Before our conversation, Waters had recently interviewed the novelist Ottessa Moshfegh, whose newest novel, Lapvona, tests the limits of taste in a manner similar to Waters’s work. Pissing, shitting, vomiting, and raping are not off limits, but are central to the anarchic action. Waters tells me that he’s always considered a rating of X or NC-17 for “a film without sex or violence” to be a filmmaker’s great challenges. Sex and violence are far from absent in Liarmouth. Indeed, the autonomous gay dick called Richard gets some, a bus burns, riots ensue, and pet owners are mauled by their pooches. I had always thought the scat and piss orgy in the finale of Don DeLillo’s Americana was the limit of perversion in American fiction, but the climax of mostly joyous rimming in Liarmouth is browner and noisier. A similar joy animates its characters with trans identities like Surprize, who transitions from canine to feline; and Lester, a dogcatcher who was raised as a dog that still loves the taste of Purina.

Lately, Waters has been an outspoken if not particularly outraged critic of political correctness. He tells me that Poppy and her militant bouncers are his way of gently satirizing contemporary activist culture. The strategy speaks to the power of the absurd and the surreal: You can sympathize with the desired rights of an imaginary oppressed group while recognizing that their quest for recognition might come into conflict with the desires of customers who bought tickets for the quiet car on an Amtrak train. It’s hard to be offensive with a touch so light.

It’s a sentiment he echoes in interviews and his one-man-show, which passed through London earlier this summer before he presided over the popular themed adult sleepaway camp, Camp John Waters, in Connecticut. It occurs to me that a brilliant work of fiction could be written about the camp, where campers spend their days as characters from his films; a synthesis of Waters’s films, his prose, and his life—potentially a postmodern masterpiece. Our conversation ends before I could voice the thought. And who cares? John Waters is not short on ideas.

in your life?

in your life?