This week the Armory Show returns to New York for its 2022 edition in its new, post-pandemic home at the Javits Center. But for the first time in the storied art fair’s history, the event brings together three voices with related curatorial practices, offering a distinct, unified lens to engage transcultural questions in contemporary art. Heavyweight curators Carla Acedevo-Yates of the Museum of Contemporary Chicago, Tobias Ostrander of Tate, London, and Mari Carmen Ramírez from the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston each lend a Latin American and Latinx viewpoint to this year’s iteration of the Focus and Platform sections, as well as the fair’s curatorial leadership symposium. Galleries in the Armory’s wider programming have also stepped up and taken the initiative to present artists that compliment this year’s speciality mission. Ahead of this year’s exhibition Cultured highlights five of the most dynamic legacy and emerging Latin American and Latinx artists on display throughout the fair this week.

Above: Rodolfo, 1995, Alejandra Fenochio, acrylic on canvas, 31.5 x 98 inches. Image courtesy the artist and Nora Fisch. Photograph by Adrian Rocha Novoa.

Tanya Aguiñiga

Volume Gallery, Chicago

Growing up in Tijuana, Tanya Aguiñiga, 44, recalls crossing the Mexican/California border daily to attend school in San Diego, witnessing people sacrificing their lives every day trying to make it to the United States. As a child, she struggled to understand why being born on one side of a line determines a person’s ability to move freely. Along with collaborators in a massive quipu project (an ancient Andes system of record keeping comprised of fibrous strings) along both sides of the divide, Aguiñiga captured the liminal realities on the brink of the two countries by asking U.S./Mexico commuters about their perspectives: thousands of people from San Diego to Brownsville, Texas that each contributed a knot that represents their individual borderland experience.

The artist’s practice showcases the power of craft, as much a medium of expression as a subversive, collective force against oppressive culture. Based in Los Angeles today, Aguiñiga creates entrancing fiber art, furniture, and site-specific installations—rooted in Chiapas artistic traditions and her Rhode Island School of Design training—from a range of materials, such as wool, rope, and synthetic hair. This year, Chicago’s Volume Gallery showcases a collection of Aguiñiga’s recent iced-dye weavings—a reaction to the grief, rage, and exhaustion she felt during the pandemic—that warrant a trip to the Javits Center on their own.

Maria Nepomuceno

Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York

Maria Nepomuceno’s visual language is at once painstaking and poetic. The Rio de Janeiro artist, 46, fashions saturated, spiraling worlds of beads, resin, gourds, straw, fiberglass, and braided cords that feel biomorphic with echoes of fellow Brazilian artist Ernesto Neto’s monumental nets or the brilliance of textile master Sheila Hicks (the latter of whom, as it happens, is also on offer at Sikkema Jenkins & Co’s Armory booth this year). But Nepomuceno has a distinct perspective that makes her knitted compositions stand out in any group exhibition or major art fair. Drawing on methods of craftsmanship that she honed with a group of women in Northern Brazil—and sometimes aided by volunteer artisans—the artist’s work alludes to botanic life, while the recurring spiral motif harkens the infinite course of time. Indeed, her sculptures pulse a kind of natural energy and are not to be missed at Armory this year.

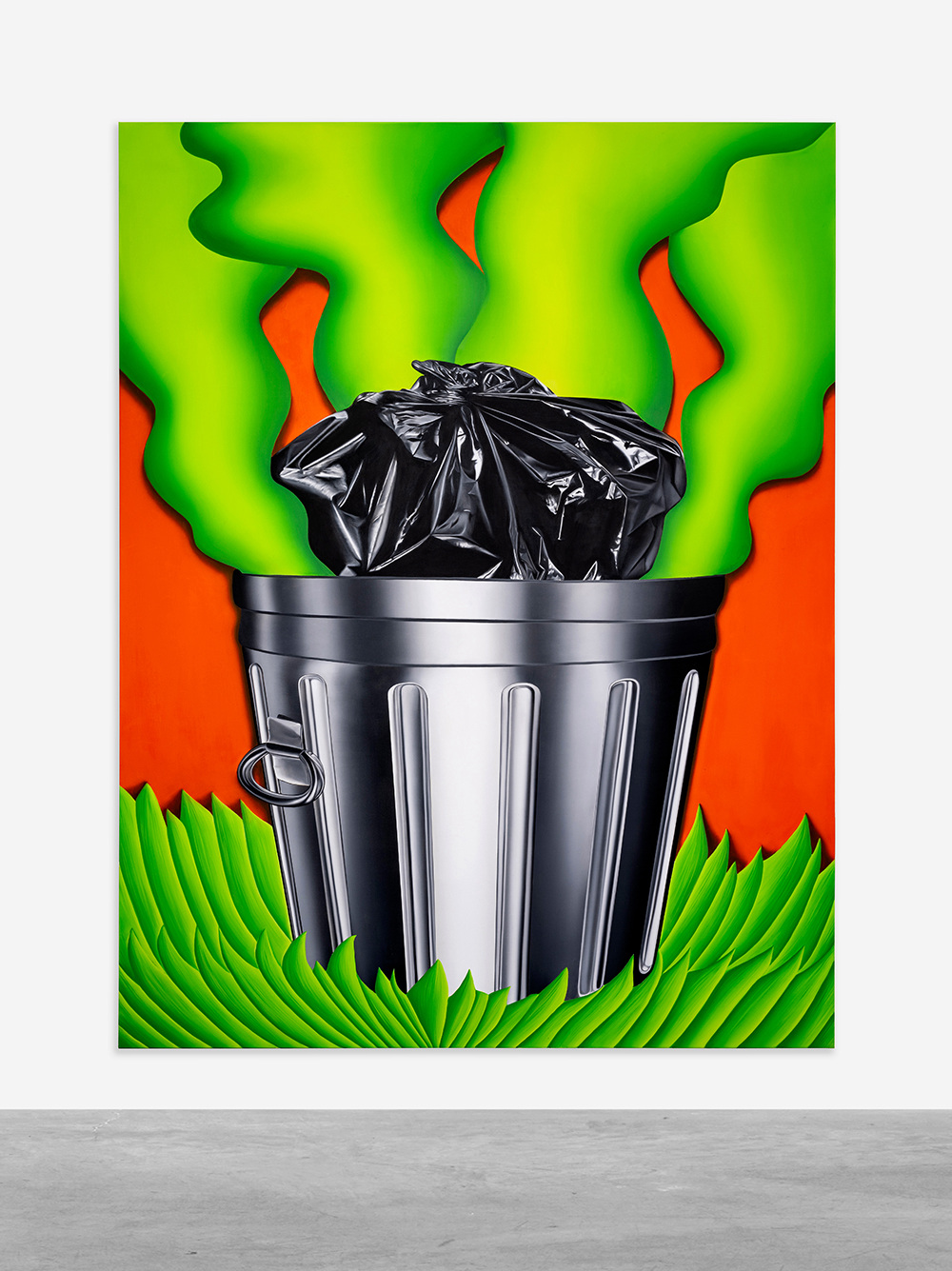

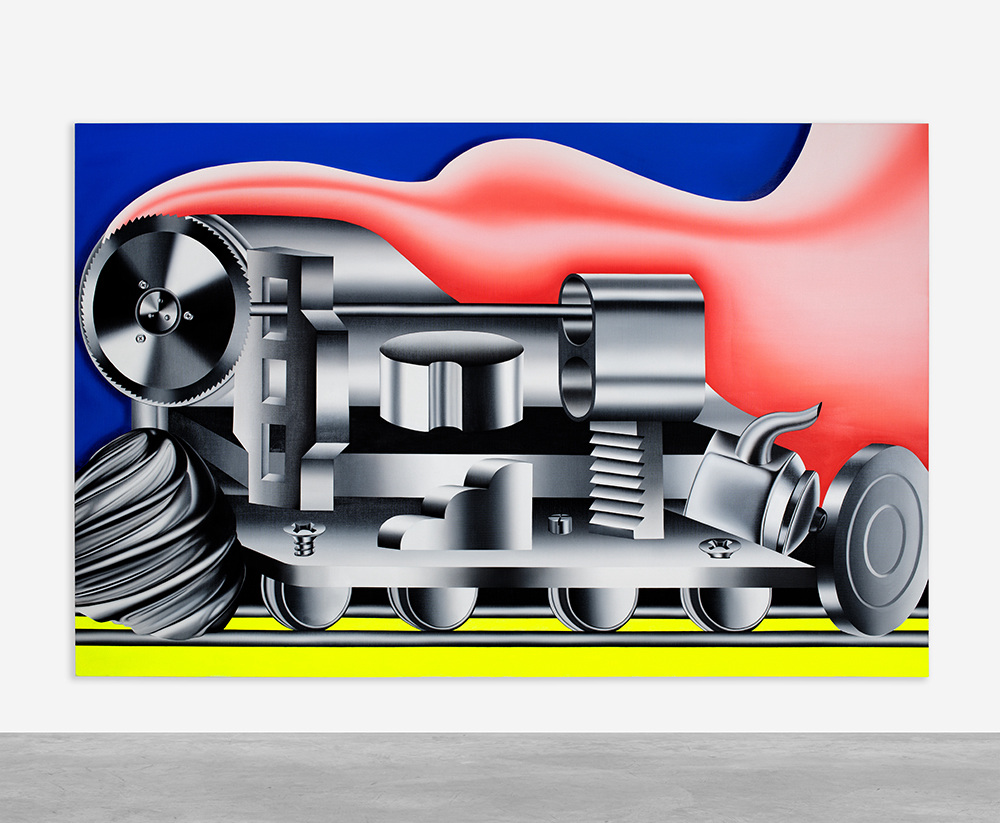

Rafa Silvares

Peres Projects, Berlin, Seoul, Milan

With punk orange and acid green, São Paulo painter Rafa Silvares, 38, creates supersonic tableaus of household detritus—tin foil, a telephone receiver—and metallic machinery that manage to ignite a sensory reaction. From garbage cans and smoke plumes to anthropomorphic pipes and tubes, Silvares’s practice straddles Pop and Futurism in a metaphysical industrial-scape. Previously a graphic designer and digital illustrator, the artist celebrated his debut solo show “Smoked Ham” last fall with Peres Projects in Berlin, where he lives, and has an upcoming exhibition next month in the gallery’s Milan space. This being his inaugural showing in New York City, experiencing Silvares’s work in person at the Armory is a must. But don’t be mistaken by the playful palette: for the artist, train chimneys and trash bags are the harbinger of an environmental apocalypse.

Alejandra Fenochio

Nora Fisch, Buenos Aires

“We are presenting Alejandra Fenochio for the first time outside of Argentina, bringing some of her large nude portraits from the nineties as well as a group of small paintings depicting the shores of local rivers and the native plants growing at their edge—nature battling human-made pollution,” says gallerist Nora Fisch. Still underground to many U.S. and European buyers, Fenochio, 60, is known for her nude portraiture of queer friends, actors, and dancers in post-dictatorship Buenos Aires, celebrating the burgeoning counter-cultual night club scene of the late 1980s and '90s. Despite being over three decades old, her works thunder with current urgency in their bold gender fluidity and contemporary, majestic aesthetic. In recent years, however, the artist has focused on social and climate issues that she believes to be most pressing for humankind: poverty (Fenochio has painted large fictional portraits of the homeless on Buenos Aires streets), as well as the effect we’ve had on the natural environment and other species (on display at Armory). There is a distinct wistfulness to this facet of her practice, but her vernacular is strong and collectors are fortunate to encounter both sides of Fenochio’s oeuvre this week.

Priscilla Monge

Hutchinson Modern & Contemporary, New York

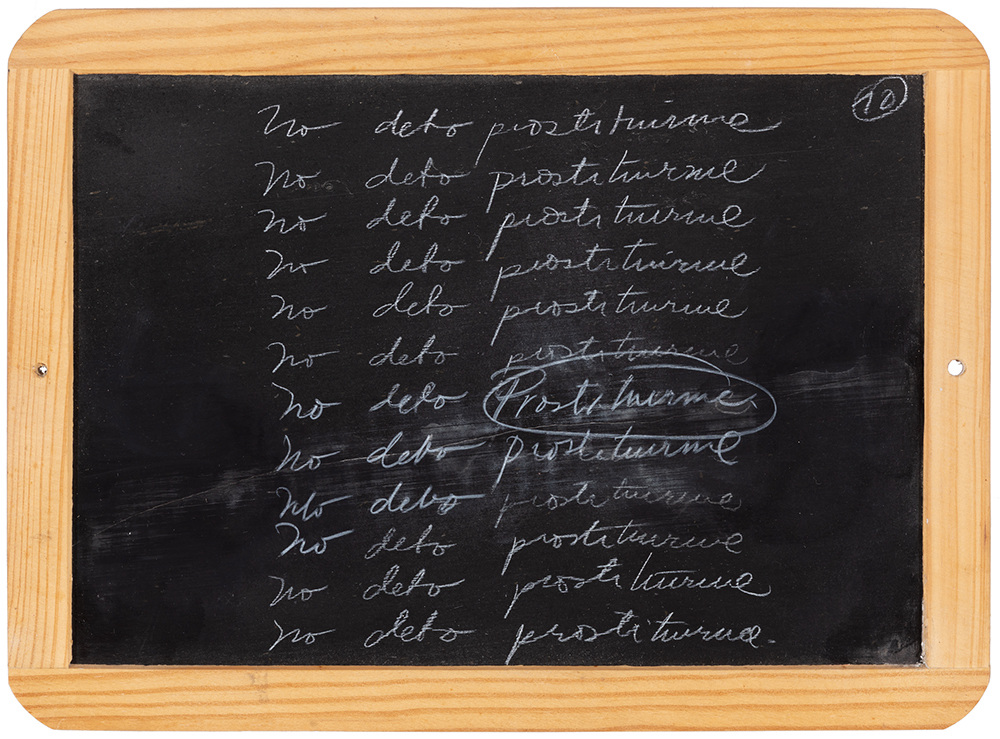

Costa Rican-born artist Priscilla Monge examines how society treats women through a range of mediums— film, photography, sculpture, and performance, using subtle humor to critique the power dynamics of daily life. For example, in The Artist Reveals Mystic Truths, Monge, 54, has painted the inside of teacups with coffee to read phrases that each end with the words “a matter of life and death.” In her “Pizarras” series, she repeatedly writes “I should not have obsessive thoughts" and “I should not cry.” Of the ten chalkboards (sold as a group) displayed at the Armory, Monge explains, “I explore the cliches about women, the dark side of education, punishment, and repetition.”

This week, New York’s Hutchinson Modern & Contemporary also presents recent works, alongside those from the ‘90s, a mini-survey of Monge, who is one of Central America’s most significant, living conceptual artists. The gallery is bringing a new suite of polaroid pieces, including one large screen print on canvas, painted with green oil paint that explores the “aspect of nature” being an “indifferent witness,” according to Monge. This is the first time the gallery has brought her to a fair, an opportunity not to pass up. Curator Clara Astiasarán explains the exceptionality of Monge’s practice as an artist who has “always resided in her way of saying things with both simplicity and brutality.”