Failed romances often leave behind abandoned plans in their wake: a hiking trip in the Alps, repainting the dining room, reading Swann’s Way together. Few of us can say we left behind something so grand as La Cupola, the clandestine vacation home on Costa Paradiso in Sardinia, Italy designed by the pioneering architect Dante Bini. But few of us are the late director Michelangelo Antonioni and actor Monica Vitti. Life is full of disappointment.

“Build me a house that smells like this pebble” was the only instruction Antonioni gave to Bini, according to an interview in 2015 with the architect featured in the Architectural Association School of Architecture Journal. The two were introduced by Vitti, who knew Bini because they belonged to the same ski club. Bini and Antonioni became fast friends and would remain so after the project was complete, even though Antonioni never paid him for the project, promising exposure instead.

After Bini signed on, he was sworn to secrecy by Antonioni, who wanted the utmost privacy regarding the project. The location of the villa was chosen for its remoteness and arid beauty. Antonioni discovered the desolate corner of the island while he was scouting locations for what would become Red Desert (1964), the title of his movie inspired by the pink sands found on the nearby island of Budelli.

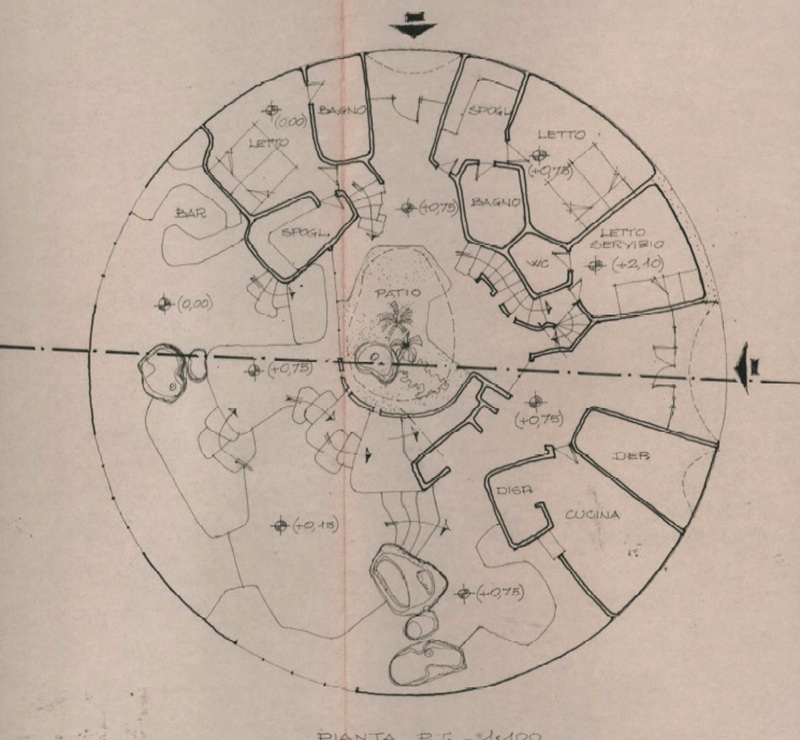

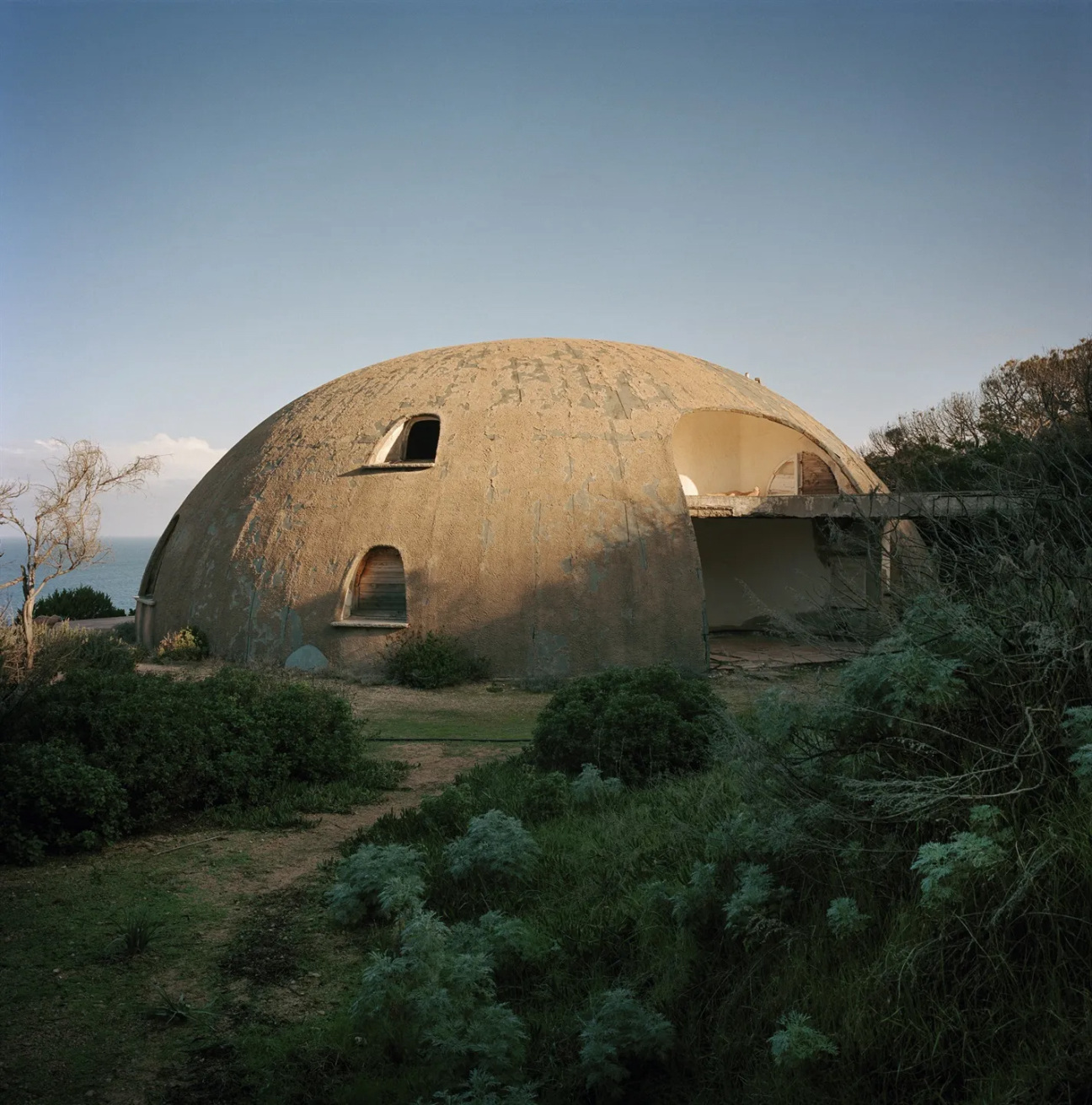

In the same year the movie was released, Bini patented his “Binishell” technology that was used to build La Cupola in the late ’60s. A dome-like Binishell can be built in less than an hour with as few as three people by using an inflatable bubble. Concrete is poured over steel beams and a circular membrane, which is then filled with air to erect the structure. After the concrete hardens, entryways and windows can be cut out and interior walls can be built to partition off the cavernous space. At its time, it was a revolutionary advancement in automatic architectural technology.

Bini, like Antonioni, had an interest in relating his work to social reality, leading him to find use for the Binishell as temporary homes for people struck by natural disasters. The domes are well suited for this purpose due to their resilience, affordability and simple construction. Most existing Binishells were designed for civic and public use, but there are plenty of residential projects as well—boldly futuristic homes at the time of their construction.

To see La Cupola today, you have to hop a fence. In need of extensive repairs, the house sits vacant. Those who dare to trespass must hack through a dense thicket of scrubby brush and shifting gravel. On the other side, they are rewarded with a stirring view of a lost utopia.

Upon approaching the home, one gets the impression they have instead discovered a strange observatory. The concrete of the imposing edifice is blended with local granite aggregate to match the surrounding landscape. A suspended catwalk stretches toward the patio entrance on the upper floor. Below is the front entrance. The rest of the exterior is punctuated by arched and triangular windows. At the back, a terrace and wide rectangular window provide views of the Sea of Sardinia. Antonioni got what he wanted when asking for it to smell like the earth; the structure’s many cutouts make for a porous boundary between exterior and interior.

In contrast with the uniformity of the façade, all the internal forms are organic. A large central space serves as an open plan living-dining area. The eye is drawn immediately to a glass wall and door leading to an atrium with a small garden; looking up there is an oculus, securing the galactic feeling. In most pictures found now, there are a few pieces of rattan furniture. However, during Vitti and Antonioni’s time a large white sofa flanked the curved wall. All the furniture was white with clean lines, consistent with the space-age design ethos of the entire project. The most striking feature of the room is the hovering staircase made of locally sourced beta rosa granite, the edges left rough giving an effect of Paleolithic glamor. Antonioni designed those steps so he could admire Monica traipsing down in the morning light, lore has it.

All of that is gone now, the house condemned, the windows boarded up. Viiti loved the place but did not go often; she didn’t like to travel by boat or plane. Their romance crumbled in the late ’60s and they didn’t end up spending much time there together after all. Antonioni kept it and went frequently, but left it for good in the ’90s, allegedly because too many tourists showed up, though he still maintained ownership for the rest of his life.

In the aforementioned interview with Bini, he came to tears after seeing a picture of the house in its advanced state of ruin. The couple might have liked it this way. Perhaps its disrepair is a testament to the toll that modernity takes on all of us, regardless of our social status. It's a theme often present in their films that has a particular relevancy today, in the wake of the pandemic.

in your life?

in your life?