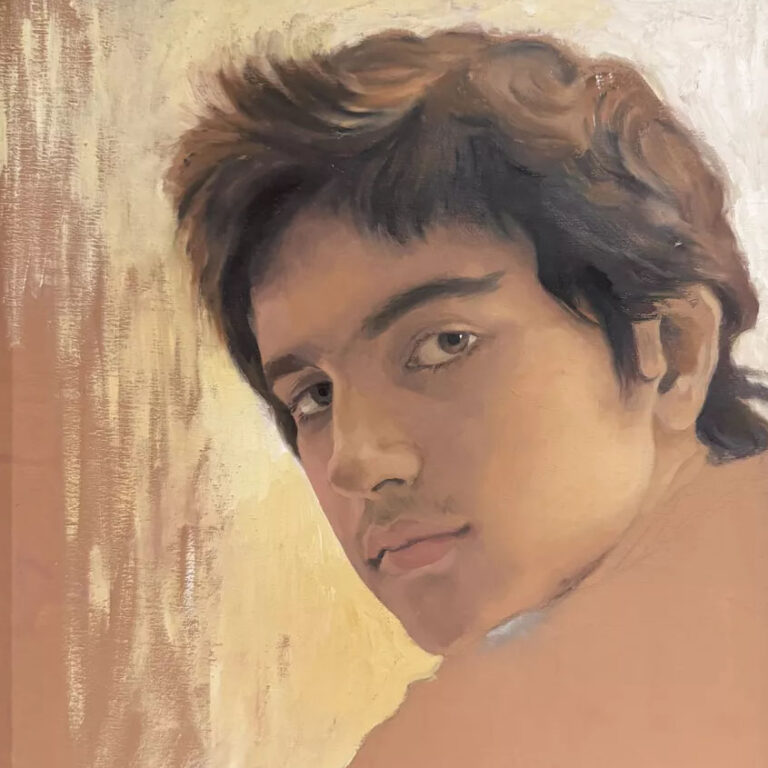

Faceted like gemstones, waves move geometrically over the surface of a swimming pool in two paintings in Manuel Solano’s 2021 exhibition “Heliplaza” at Pivô in São Paulo. Solano borrowed the title of the show from the name of a shopping mall in Ciudad Satélite, the suburb of Mexico City where they grew up. After losing their sight in 2014 due to HIV-related complications, the 34-year-old painter has been forced to work only with the images that they remember from their experience of the visual world; frequently they reconstruct vivid and striking pictures from pop culture and their childhood. Solano tells me that before they became blind they prided themself in their ability to paint “transparent or reflective objects,” which “is all about understanding exactly where there is light and where there is dark and how light is bending through space.” Solano has been told that their natatorial landscapes remind people of David Hockney’s classic 1964 painting A Bigger Splash, a comparison they politely decline. In their opinion, “Hockney did not do the work. The water in his painting does not look like water; it’s symbolized there because there’s the color blue but that's it.” And Solano is right, if you return to the painting, you’ll find that the plume of gushing chlorination meant to indicate the submersion of a body into the swimming pool just sits flatly on a smooth uniform field of blue.

The process of painterly mimesis has as much to do with observational acuity as it does with the careful and precise gesture of one’s hand. Part of what’s so striking about Solano’s work is seeing an artist rely so fully on the former of the two skills, to dissect and take apart images—Solano gets inside of the mechanics of each material’s appearance to reverse-engineer an optical encounter with it for the viewer. In another painting from 2020, an interior scene of an invented Art Deco building, Solano deals with a window of translucent bricks of glass much the same way as they do the undulating ripples in the pretend fountain. And in an earlier work from a series called Pose, based on images from the world of Michael Jackson, one finds the killer whale from the film Free Willy, used in the music video for Jackson’s song “Will You Be There,” glistening with his dorsal fin tragically collapsed as theatrical lights beam off his rubbery skin and scatter into the orca’s tank water. Nostalgia, glamorous and melancholy as ever, is as much the method of Solano’s paintings as it is their subject. Their paintings of images taken from pop culture are so remarkable because they are able to articulate not just the image itself but the feeling of seeing the image for the first time, or perhaps the feeling of an image that you have played back for yourself in your head a million times. Well-worn, the picture warbles in all the wrong places and we can imagine what it must have been like to encounter, to be pierced by, some of these pop culture icons.

In order to achieve the naturalism they demand of their pictures, Solano now works with a team of three studio assistants in Berlin where they has lived for the past two years. The rest of the team, Solano’s longtime studio manager and former boyfriend, works remotely from Mexico City helping create maps of each picture using tactile markers that guide Solano’s hands over the surface of the painting as they apply acrylic with their fingertips. Sometimes when they have to work alone, Solano uses a phone app called Be My Eyes that connects blind people with sighted people who describe back to Solano what they see them doing as they paint. Solano says, “There’s always a point where I have to “[Making images is the way] I know how to communicate myself to the world.” give up. Any feedback becomes huge in my imagination and I can’t let it run on forever.”

In the four years since they were included in Songs for Sabotage, the 2018 New Museum Triennial, their work has exploded in popularity, earning them institutional solo and group exhibitions at the ICA Miami, the Palais de Tokyo in Paris and, most recently, at the Kunsthalle Lissabon in Portugal. The new success has afforded Solano, whose paintings are often praised for their unique emotional intensity and earnestness, an all but forgotten luxury in the market driven world of contemporary art discourse; the time and space required to work on longer term projects that encompass both painting and sculpture and explore their identity through references to the movies and music that shaped it.

In the years since Solano went blind, their paintings have only become more formally complicated, delicate and detailed; when telling me this they stumble for a moment before posing it back as a question to themself. They ask why they remain so committed to representation, when they could far more easily make paintings that look another way. “I think basically I’m feeling very lonely,” they say, and making images is the way “I know how to communicate myself to the world."

in your life?

in your life?