Odessa Young pulls out a Marlboro and lights it inside her Williamsburg apartment. “I kind of want my apartment to feel like a salon,” she says. “We’re having people over tonight. I love hosting.” During our call she moves upstairs to get away from the sounds of her boyfriend cooking, preparing for guests. “My acting teacher recently said to me that I host so many parties because I’m so afraid of not being invited to things. Like to just take control of the situation. That’s probably true.”

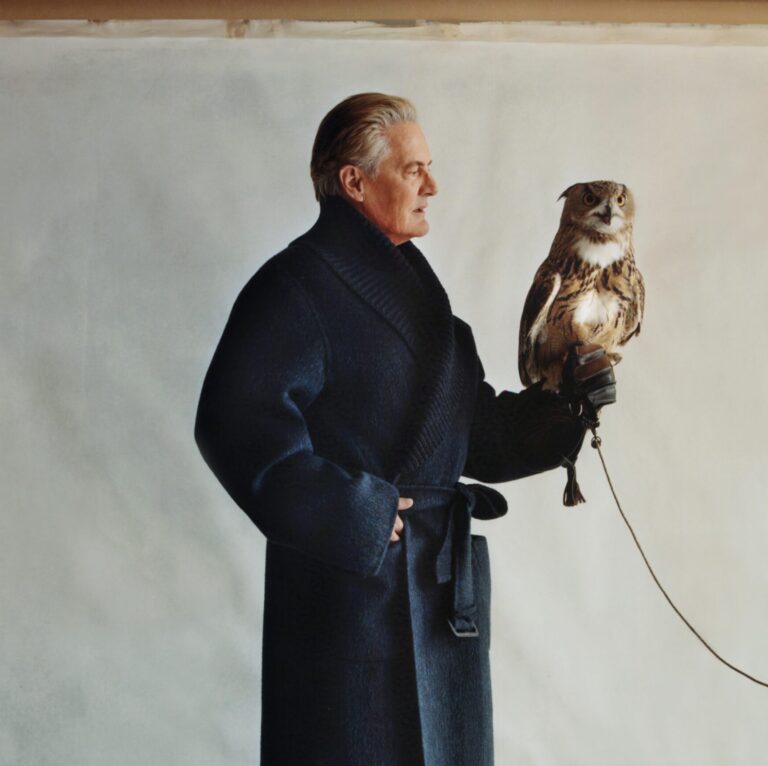

To make one’s own way, to host instead of worrying about not being invited, to carve out a space that is one’s own, are desires that have appeared in a few of the roles Young has played in her nascent acting career. Whether this is a sign of insecurity or self-assurance, or a little of both, Young tells me this with candor and a self-deprecating charm. In Mothering Sunday—which also stars Colin Firth, Olivia Colman and Josh O’Connor—the 23-year-old Australian actress plays Jane Fairchild, a writer who works as a maid for a wealthy family in post-WWI, pre-WWII England. Jane in her adolescence navigates intimacy, loss, the pursuit of an artistic practice, the struggle to emerge from her working-class situation. Young tells me, “Eva [Husson, the film’s director] was very, very hell-bent on embracing the ugliness of insecurity and the struggle to ride through it.”

The film is an update to the Upstairs, Downstairs (1971) narrative; instead of only getting snippets of what goes on downstairs, Mothering Sunday follows Jane and her internal life closely. Flashing between her early 20s and her mid 40s, Jane tells the story of her youth, reflecting on the period of her life as a servant and her discreet love affair with a friend of the family who employed her. Young, who plays Jane at both ages, is growing into more mature leading roles in her career, and recently starred opposite Elisabeth Moss in Josephine Decker’s romantic melodrama Shirley.

When I ask her about playing the same character at two different ages she says, “I think it was the subtle differences in the way that it was written, the way Jane holds herself or the way that she speaks. She found the ability to speak as opposed to just be seen and not heard for most of her life. Her internal narrative or internal struggles are made external in the kind of older version of Jane once she’s actually found herself, found agency.”

The gap between the two iterations of Jane mirrors the paradigmatic shift happening more broadly in the film’s atmosphere. The affair with the boy took place during a period, flanked by the wars. It was the great pause of the service era, money was running out, everyone’s sons had died. Young studied up on this particular part of the century by reading diaries and journals written by maids. She says, “Jane is in fact their only maid because they have to let everyone go because there’s kind of nothing to do. Everything’s lost and everyone’s just floating around trying to do what they once did.”

The film’s setting was timely as it was shot during the tail end of lockdown, when the pursuit of normality, to return to what we once did, was at its height. “It makes you feel crazy,” Young says with a hint of exasperation, “when you see that the structure of the way things are done is so blatantly disintegrating but everybody’s pretending that it isn’t.” After being sent auditions and scripts in the early days of the pandemic and questioning the purpose of these projects that weren’t going to be made, Young says she almost quit acting knowing she wanted to figure out what she was going to do if not act. In a year that put everyone’s creative pursuits into question, and had a lot of people questioning the validity and sustainability of their artistic lives, she says she felt estranged from the world of acting.

At the same time Young says she benefited from this opportunity for reflection, questioning the existing structures of the film industry. “I think that the amount of stuff that’s being made is really dangerous for the future of film,” she says. Since streaming platforms have become even more powerful, with more money to produce incredible amounts of content to supply the demand, the almost compulsive production makes the work suffer: “They’re trying to make as much for as little as possible… 90% of what I’m reading is super nihilistic either in its message or in its conception and that doesn’t interest me.” The aforementioned desire to host her own party, to be in control of her own situation, seems obvious then, practically necessary.

Young says the experience in a changing industry has forced her to question the meaning of her work and has driven her to pursue projects that interest her, those she wants to see out in the world. She’s currently at work on a dramatization of the 2004 true crime docuseries The Staircase in which she plays the adopted daughter of Michael Peterson, the suspected murderer. Young tells me, “It’s interesting playing a person who is quite documented. It’s like the first time I’ve ever had to choose between imitation and representation of a real person.” The miniseries is creator Antonio Campos’s passion project. “I’m not just going to do jobs just because I love acting. There’s a reason why I love movies and it’s because they have the power to make people ambitious or hopeful about the direction of the world even if they show the opposite of that.” It’s as if Young searches for this same drive in the filmmakers she chooses to work with, whose projects are guided by a commitment to good work rather than pressure from platforms to churn out a product. She’s come to terms with the fact that this might mean making sacrifices. “I’m fine with never being comfortable if that’s what it means.”

in your life?

in your life?