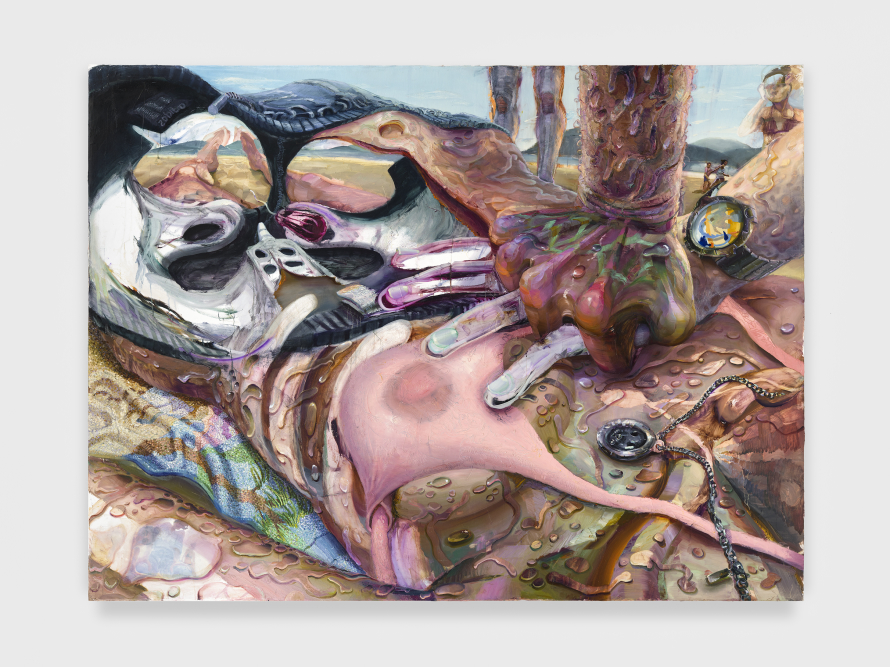

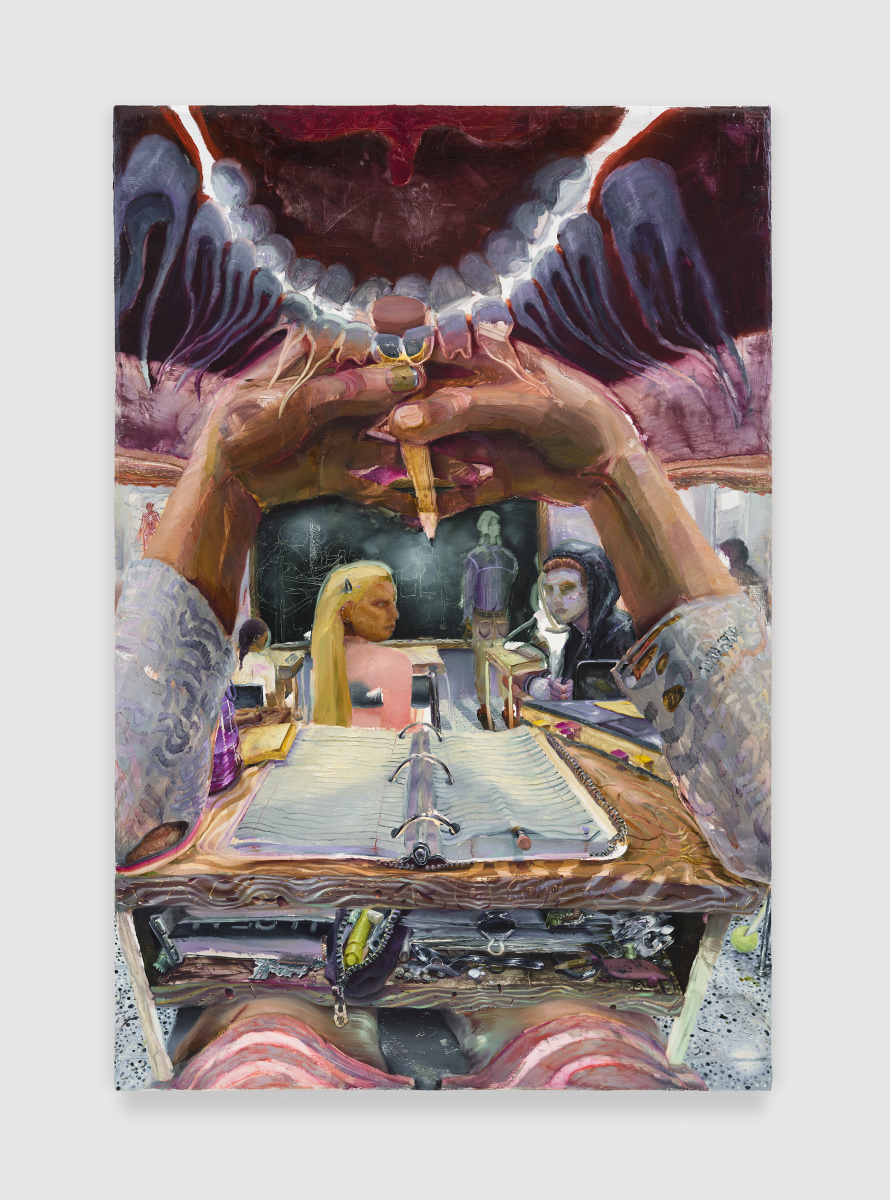

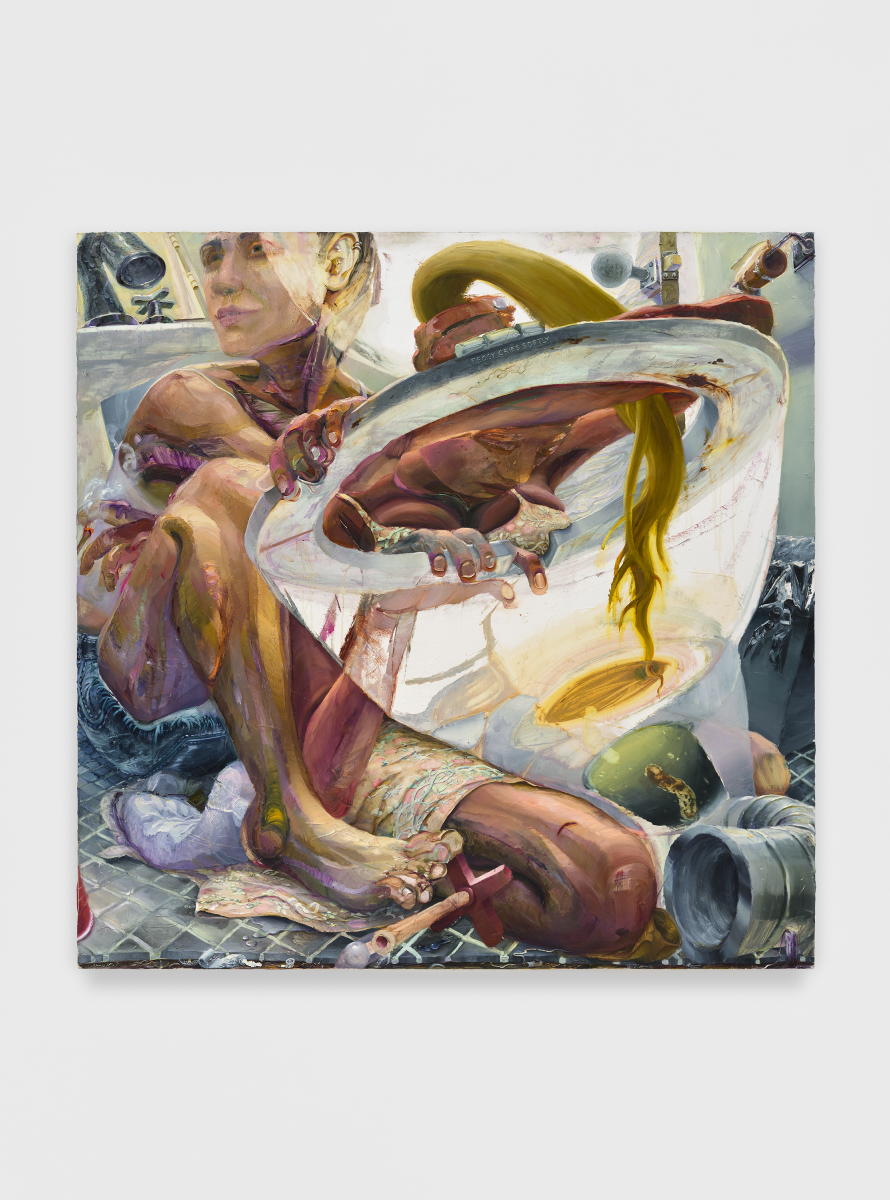

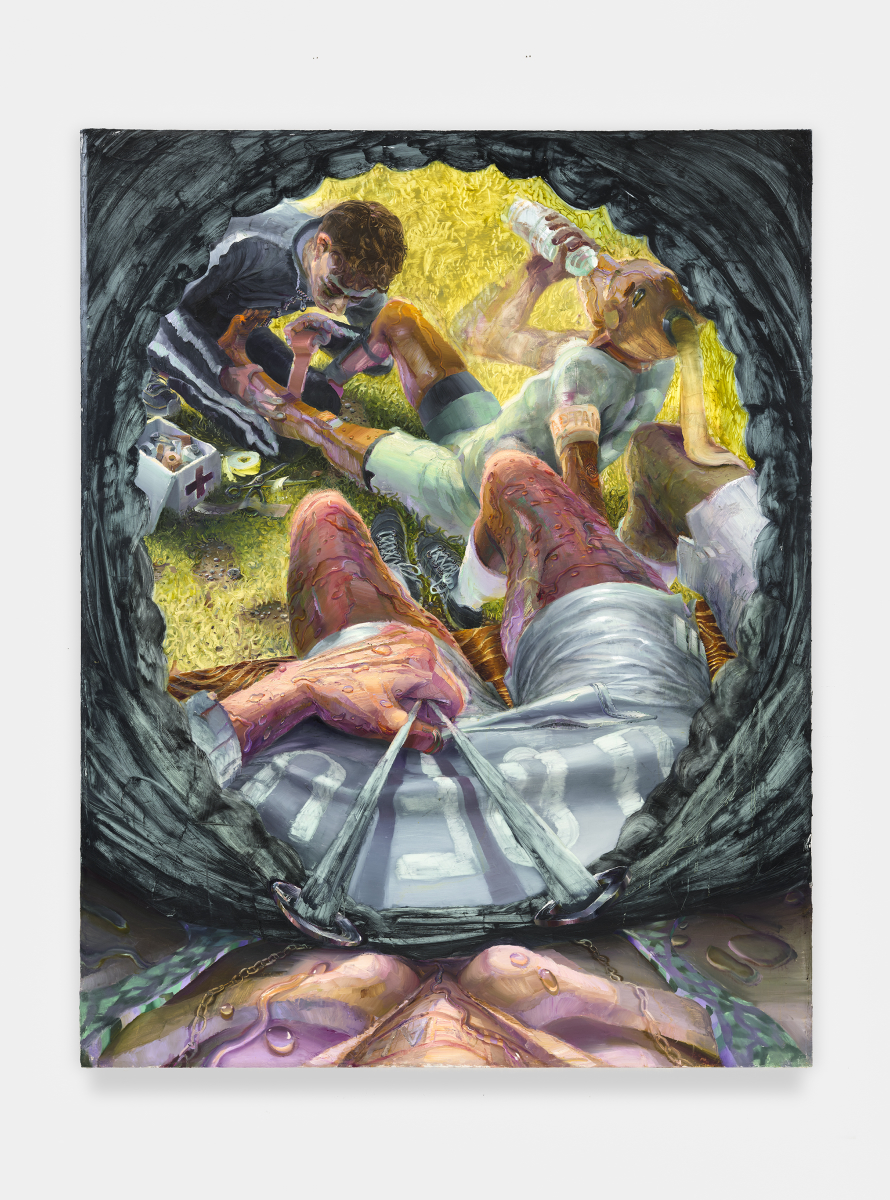

Danica Lundy’s paintings are arresting, visceral, and unsettlingly familiar. Blending references to teen movies with her personal experiences, Lundy paints dark scenes of classroom insecurities, sports injuries and chaotic high school parties. She captures the moments in adolescence when the dregs of childhood innocence fade away and the adrenalin of a world on the verge of adulthood freedom rushes in, as if visual representations of the reckless teenage feeling of being indestructible. Like trying to recall a dream, Lundy’s paintings toe the line of narration, yet her choice of perspective defies logic, giving the viewer a glimpse of fragmented episodes about to erupt. With her first New York solo show, “Three Hole Punch,” having just opened at Magenta Plains, Lundy reflects on the layered influences hidden within her latest body of work.

Annabel Keenan: First of all, congratulations on your well-deserved first solo show in New York. How does it feel to have achieved this milestone?

Danica Lundy: Thank you, Annabel! It feels dreamy. I’ve been living here for six years and have shown mostly in Europe, so shipping the canvases across the bridge to Manhattan instead of across the pond is pretty exciting. I haven’t been able to see any of my shows in person since 2018.

AK: In the past, your works have had incorporated references to personal experiences. Is this still the case with the paintings in the show?

DL: With the way I currently work, it would be impossible to completely divorce myself from the subject matter and content. The compositions usually start with a strong feeling, and then they pull in the outside world. Ultimately, I think a painting should leave you with a strong feeling too.

AK: Some of the feelings that come into play in your paintings derive from chaotic scenes of adolescence and teen movies. What are you interested in conveying with these references?

DL: Cinema might be the most widely accessible visual art form. Especially now. As a culture we are obsessed with the film industry. The idea of “behind the scenes” (a peek at the artifice) is a well-understood mechanism: we know how things are made, the equipment, green screens and special effects. But in good cinema, even equipped with that knowledge, we are swept up in the story. Most of my paintings point out the fact that there’s a life beyond the set, that the boom’s just out of sight. That there’s a director, a crew, a trail of their debris left behind.

I have always been a sucker for teen movies as a perfect arena for drama and chaos. It’s an emotionally unstable time where those in the throes of adolescent abandon go right up to the edge—to establish where that edge is—to peek at whatever danger lies in the unknown. Painting that edge feels potent because it helps direct my brush in a technical choreography. It evokes the feeling of occupying a teenage body, where everything is in flux. I try to push that novel feeling into the paint itself.

AK: The perspectives you choose, like looking down through the body into a set of ribs, add a visceral quality and heightened sense of self-awareness. How did you develop this perspective?

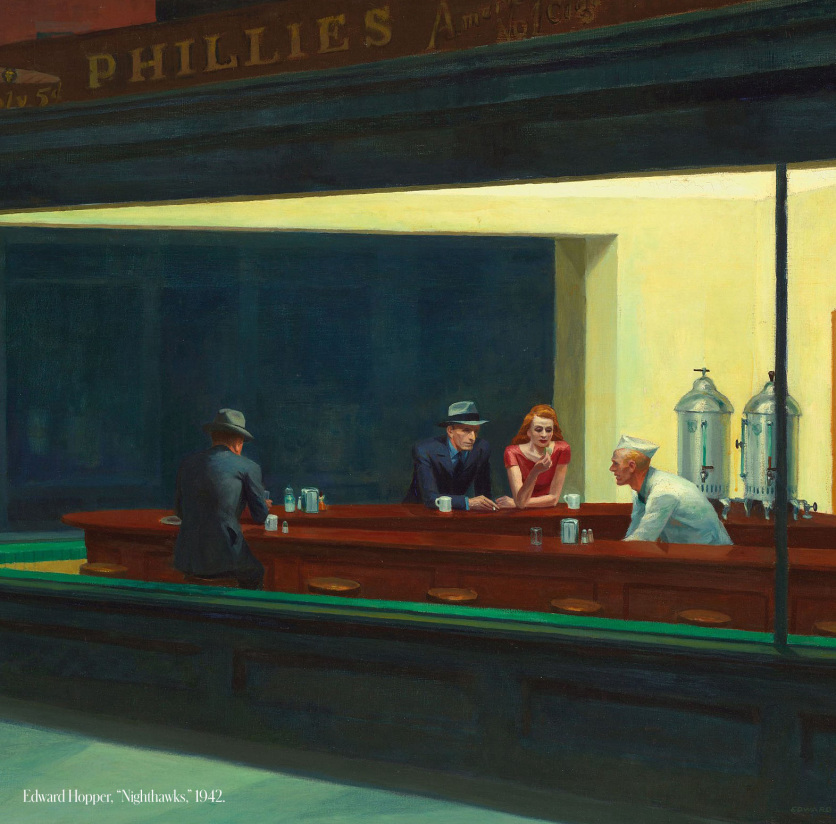

DL: I’m not completely sure how this came about. It just made sense. Pulling away things to reveal a function, to look in, to highlight windows and doors into the body or picture plane is a preoccupation of modernism onward, but it goes back further. For example, the biblical story of Doubting Thomas has been depicted since the 5th century: "Unless I see the nail marks in his hands and put my finger where the nails were, and put my hand into his side, I will not believe it." Or Rembrandt’s portrait of Agatha Bas, whose thumb slightly overlaps the frame she sits in, nudging into our space and blurring the boundary between inside the painting and out. And there’s Michelangelo, sneaking into morgues at night to dissect and understand. We live in bodies we can’t usually see into, so why shouldn’t painting be a forum for that imaginary observation? Also, painting has historically leaned on Albertian perspective, but it is just one way to organize the picture plane. It isn’t necessarily an intuitive organization to show how we actually experience the world.

AK: Connecting the film references and your unique perspectives, your painting Kissing Cavity makes me think of the scene in Beetlejuice where the main characters have their stretched, scary faces on and when they open their mouths, there’s this giant set of teeth and huge red tongue with tiny eyes looking out. Kissing Cavity is as if the viewer is looking out from those eyes inside their mouths. Do you approach your paintings with specific references in mind?

DL: I absolutely love that this painting brought up that scene for you. I conceived of Kissing Cavity from a “boob’s-eye view,” imagining painfully visible, budding breasts having their own visual agency over the scene. Most of the paintings have at least a few cinematic references. The Lolita-esque hitchhiker from Once Upon a Time in Hollywood has her foot against the surface of the canvas in Ferry Ride, for example.

AK: There’s a sense of tension in your work. The figures seem carefree, yet they’re engaging in activities that have the potential for danger or harm. You’ve captured that precarious moment in teenage years where nothing seems to matter, but the activities suddenly accessible come with a higher risk. Would you say your subjects are dark, or could you call them a celebration?

DL: Very well put, I couldn’t have said that better myself (and I’ve been trying for years). I’d say the subjects are receptacles for chaos and danger, improvisation, risk and ecstasy. There’s no doubt there’s darkness there, but there’s light and humor too. All those things are possible at a kegger, you know?

AK: What is the significance of the exhibition title “Three Hole Punch?"

DL: There’s this Eminem lyric that says: “I’ve been dope, suspenseful with a pencil / Ever since Prince turned himself into a symbol.” Here, we’re offered at least three ways to derive meaning: Prince himself was an icon, a sex symbol. In 1993, Prince changed his name to a literal symbol. And then in the arrangement of the song—Dr. Dre’s handiwork—a cymbal instrumental pings, creating an almost synesthetic, self-referential link to the musical medium. In one sentence, a playful triple entendre somehow manages to morph into a multifaceted, multisensory cultural time stamp. I think good paintings work that way too.

When I look at paintings that really move me, their ultimate meaning never arrives by way of just the paint, or in the image and the historical/contemporary symbolism it carries. There’s always a third thing, usually hard to put a finger on, whose meaning is synthesized in my body.

The title attempts to translate all that, while incorporating other motifs that appear in this body of work. The words physically echo their own meaning: three one-syllable words that punch into the page. It sounds intuitively violent alone but is banal when looked at in context. It refers to adolescent subject matter: a tool once necessary for note-keeping in high school. And paper/drawing is integral to the painting process. There’s also a crude allusion to female anatomy. Incidentally, each floor of the exhibition has three paintings.

AK: The scale of the works in “Three Hole Punch” is so impressive. Why do you choose to work on this large scale?

DL: My very athletic sister took to kiteboarding a decade ago. She explained to me that she’d rather be overpowered by the wind and have to figure out how to harness it with her kite and body than be totally in control. Perhaps a feature of her affinity for risk as a teenager. My body would actually crack if I tried this, but I can relate to the metaphor. Painting at that scale is an all-encompassing experience. It’s stimulating, like a way to settle into the brain and bones of the painting and shake the whole thing awake. I want to give the viewer a real-world (or larger) scale to get sucked into.

AK: What else is in store for you for 2022?

DL: I’m preparing for a solo show that opens in July with White Cube in London. I’m currently tackling a smushed banana in a painting of a locker room.