Choichun Leung is, as she puts it, the “product of a Chinese takeaway upbringing.” The artist grew up in Wales—her mother from the UK, her father from Hong Kong—where, from a young age, she began cooking and working at the family restaurant. She says that while her father was also creative, his circumstances as a Chinese man in the 1950s meant he wasn’t able to act on it; but as she watched him draw or make things with chopsticks after work, she caught on. She has a clear memory from about three years old of making playdough sculptures for a school competition. As a shy kid, Leung says art often allowed her to communicate—both with others and herself: “Art was my imaginary world that helped me disappear from my reality.”

With time, Leung had her hands in various mediums, and eventually chose to pursue metalwork with her education. She felt both a spiritual connection to the trade—she recounts visits to Chinese monasteries in her late teens that inspired a “fascination with ceremonial objects”—and believed it was a function that had to be learned, from welding and forging to raising a bowl. She believed that painting, on the other hand, would come from her. And it did.

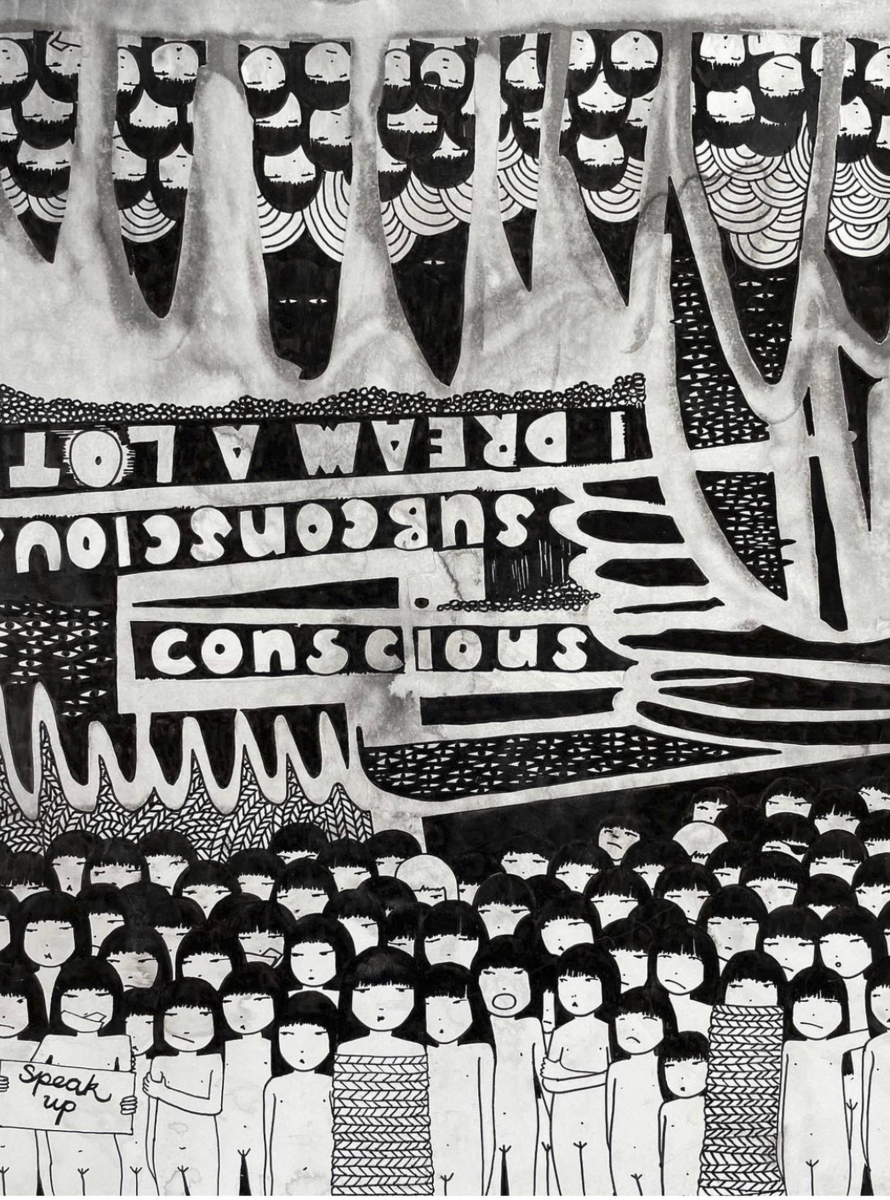

Leung had always been a doodler, oftentimes depicting the heads of three Chinese girls in her work. Once, a friend asked why she stopped drawing at the characters’ heads: “He said, ‘why don’t you just carry on drawing the bodies?,’ and I began to feel that self-restriction telling me a story. I realized what was covered was a story of all the emotion that I had kept in.”

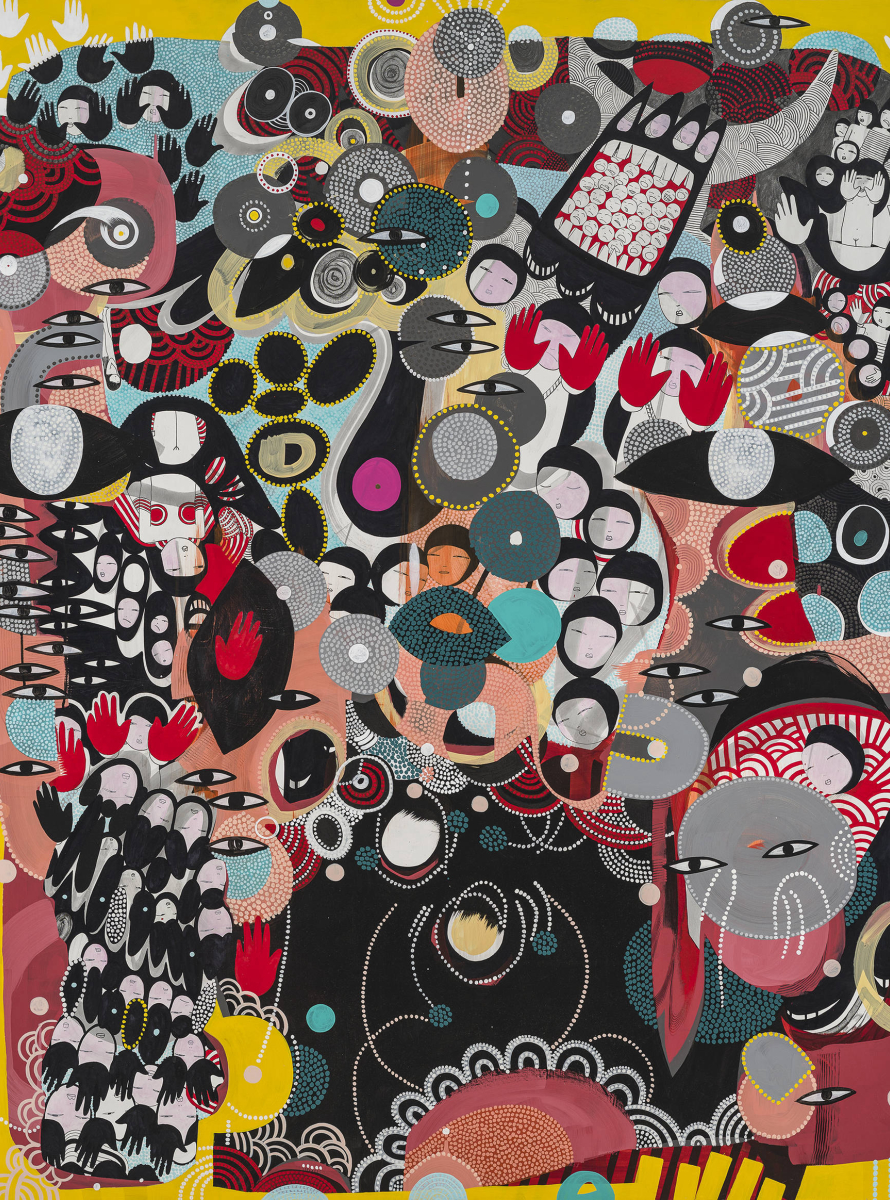

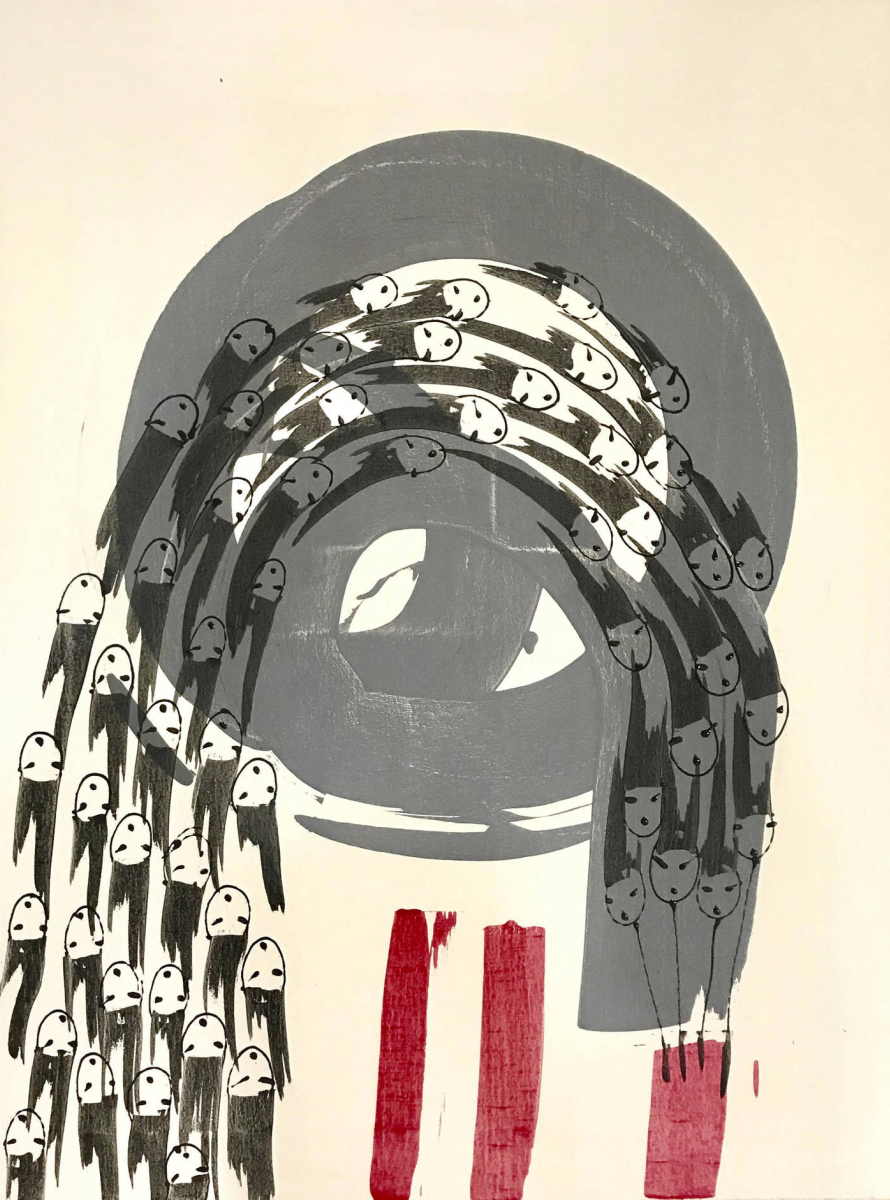

In the years that followed her friend’s prompt, Leung began to visually communicate with herself, drawing more and more Chinese figures as she reconciled memory and healing. “When I was drawing,” she shares, “I was remembering how I felt as a child.” At around age six, Leung has a memory of being sexually abused, and because she never approaches a painting with an intention, she shares how the story of her past began to reveal itself to her, thus fueling her journey as a survivor. Today, Morton Fine Art in Washington, D.C. opens Leung’s solo show, “The Watchful Eyes,” which amalgamates previous work from her journey with The Young Girl Project and otherwise.

As she has begun to exhibit these paintings, Leung has witnessed how her work catalyzes dialogue around childhood sexual abuse. “These young kids are so open when they see the work,” Leung says. She shares that children will point out certain parts of her work—a girl hiding, a depiction of self harm, hands up to cover a child’s face—and ask what they mean. “I’ll say, ‘Well, she’s upset because somebody touched her vagina,’ or another graphic action phrased in a way that is most accessible to children.” Consequently, Leung’s paintings have become a channel for conversation around consent, allowing parents and their children to have honest dialogue around traumatizing events. Leung’s ability to document her own stories, both subconsciously and more advertently, has become a source of relief and education for many.

This year, Leung has turned her series of paintings and their ensuing discourse into an nonprofit, The Young Girl Project, that strives to destigmatize conversations around the sexual abuse of children. In conversations with survivors, Leung says she observes children feeling understood. In addition to being a resource for help, the organization asks that everyone who sees the project share it with five friends in some capacity. “We’re working to take something that is taboo out of that arena [and] into the mainstream in order to dispel shame,” the artist explains.

As for why she thinks her work has resonated with survivors, it all comes down to art as an integral method of communication, particularly for children. “Children that have been abused don't have the words to express it sometimes,” she shares. Almost accidentally, Leung has mimicked the work of therapists and community workers who are identifying cases of sexual abuse. “Using art helps [children] discern what has happened to them—by asking them to draw or observing the subject matter of their [existing] drawings,” she says.

Ultimately Leung hopes to create a community that advocates for the most vulnerable facing of sexual abuse. And, in doing so, she wants to teach children to think for themselves. “This is about defying authority—saying no to an adult who’s telling you to do something you don’t want to do,” she shares. “It’s all about connecting to your gut and your intuition. If you feel something isn't right or wrong, trust that and act upon it.”