Clara Ha, director of Tribeca’s Chart gallery in New York had long wanted to stage an exhibition of multigenerational Asian American artists. In a year marked by shocking, violent crimes against Asian people in the Unites States, the need for such a show became increasingly clear. “As a gallerist and first generation Asian American citizen with a platform, I felt I had an urgent responsibility to present this exhibition,” says Ha, adding, “The Atlanta tragedy was a watershed moment that ignited a long overdue public acknowledgement and collective response to the escalating racial tensions and acceleration of hate crimes against Asian Americans in this country.” Honoring the eight victims of the tragic shooting—six of whom were women of Asian descent—with its title, “8 Americans” explores themes of collective identities and shared histories and celebrates the vibrance and creativity of Asian American artists.

The exhibit name is also nods to the historic “Americans” shows that began in 1942 at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. With iterations including numbered shows like “12 Americans” and “14 Americans,” the series continued for decades as studies of specific moments in contemporary art in the U.S.

Heavy as the impetus of ”8 Americans” may be, the works in the exhibition address the experience of being Asian American more broadly. An underlying subject in the show is skin and the changes it endures and reflects.

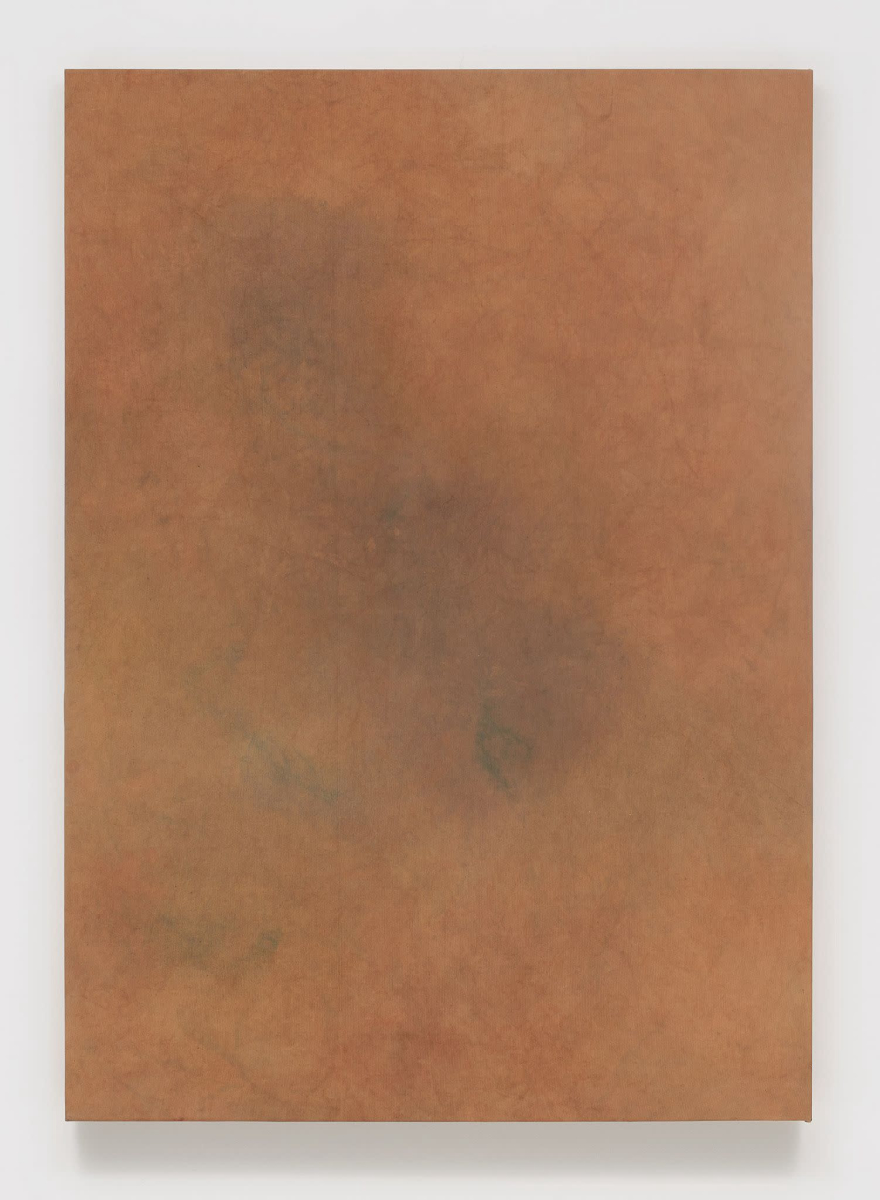

Welcoming the viewer to the gallery is a painting from Byron Kim’s “Bruise” series, which was first shown at James Cohan in 2016. The works in the series appear nearly monochrome at first, but upon closer inspection reveal subtle hints of veins and hematomas. Kim makes the works by dying raw canvas that has been boiled, using oil-soaked rags to rub pigments into the surface. The colors seep into the canvas in the same way blood seeps beneath the skin as a bruise evolves.

Titled Mineral Multitudes, this first painting in the show is a lighter blush with hints of deep blue pooling towards the center. Darker and deeper in color is Evidence of a Struggle, perhaps representative of a darker skin tone, or the deep auburn of a bruise at its freshest state.

Like the number eight with its layers of meaning, bruises are laden with inherently contradicting symbolism. Bruises can be triumphant tokens of athletic victory and markers of survival. They can also be tragic signs of pain and suffering. While Kim’s work bears evidence of pain, bruises are also visual markers of healing and the body’s physical proof of regeneration.

Leaning against the gallery wall next to Kim’s dark bruise is a series of wood sculptures by Jean Shin. Each was made from salvaged branches of a fallen hemlock tree from Olana State Historic Site, the former estate of Hudson River School artist Frederic Edwin Church. Hemlocks were highly prized for the tannins in their bark, which were used in the booming leather industry. Paying homage to this long relationship between hemlock and leather, Shin debarked the branches and wrapped the wood in deadstock leather, creating a new skin.

Also working with sculptural forms, Jennie Jieun Lee creates fragmented, abstract faces and masks out of colorful ceramic. Appearing both added to and subtracted from, there is a sense of evolution and mutability in her works. They are imperfect and fractured, yet they feel resolute, as if all the individual fragments make up a solid whole. Looking at the faces hidden in the surface, it’s hard not to think of them as a reflection of the human experience and self-preservation. The scars, smudges and marks are all evidence of the past and the personas we adopt as we enter different stages of our lives.

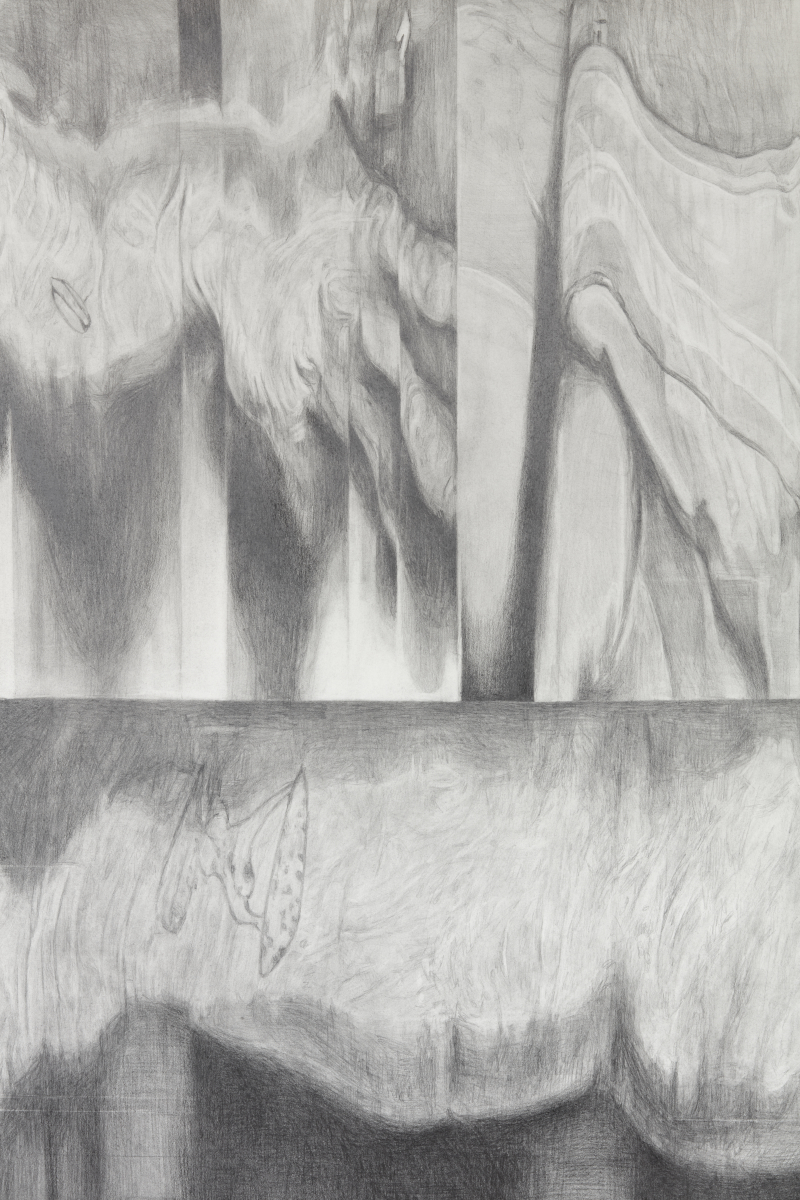

Also touching on this idea of identities evolving over time, Kang Seung Lee created a powerful, continuous three-channel video of fragmented scans of bodies. The work, titled Skin, features scars and tattoos of the artist’s fellow activists and artists in the Los Angeles queer community. The scanned bodies come together to form a scroll of somewhat recognizable parts, a collective identity and representation of shared experiences. Much like the skin in Kim’s paintings, the bodies of Lee’s subjects bear evidence of moments of pain and healing.

Expanding the conversations addressed in “8 Americans” beyond the gallery walls, Chart created a chain letter that asked the artists to write about their personal experiences and invite others to do the same. The responses are shared publicly on the gallery’s website to encourage further conversations. Ha came up with the idea for the chain letters after reading the anthology of correspondences between artist Christopher K. Ho and curator Daisy Nam in Best! Letters from Asian Americans in the arts. Chart’s letters begin with Ha’s correspondence with Ho and Nam.

In a year marked by racist violence against Asian Americans, “8 Americans” is not only appropriate, but necessary. The rich selection of works encompasses many of the important conversations on identity, suffering and perseverance that art is being used to communicate. While a somber memorial to the eight lives taken in March in Atlanta, the show is also a welcome window into a vibrant group of artists.