"Since the breakup, our way of working has become cleaner,” comments Hans Berg on his shared artistic process with fellow artist Nathalie Djurberg. In between install of their latest, most intimate exhibition yet, “Can’t Keep it in, Can’t Lock it Away,” curated by Silvana Lagos and staged at art advisor Eva Livijn-Olin’s home in Stockholm, the Swedish artist duo joins me via video call. “Wow, Hans, do you have a new sofa?” Djurberg asks casually before we begin. After 15 years of cohabiting and working side-by-side in Berlin, Berg now lives in Stockholm and Djurberg in Allingsås, on opposite sides of Sweden. “We talk every day, perhaps more than before,” they say, finishing each other’s sentences. I fall under the spell of their collective voice: contemplative, vulnerable, contradictory, calculating and kind, it crawls and nests under my skin.

In the early aughts, Djurberg created work under her own name with music she commissioned from Berg but “started to feel embarrassed and ashamed when audiences did not acknowledge the impact of the music.” There was a disjoint and division to their labor: Djurberg created sets, clay figures and narratives to make stop-motion videos while Berg contributed with music to enhance the viewing experience. When they became a duo, the art world had a hard time grasping their choice to credit their partnership. “That fairytale idea of the lone genius, or art sprung from a divine intervention is destroyed,” Berg adds. Unfortunately, women’s creativity has often been eclipsed by their male counterparts’ in history books: Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen and Christo and Jeanne Claude took years to publicize their collaborations and in the case of architects Alvar and Aino Aalto, Aino has mostly been credited posthumously. For Djurberg and Berg, working as a defined pair with a dynamic and shared process brought the work to a better place.

Sharing, as Djurberg put it, the “responsibility, glory and blame,” they have since conquered the art world with their prickly stop motion videos illustrating our most sequestered emotions—greed, desire, shame, revenge, submission and domination. In 2009 they won the Silver Lion for most promising artists at the Venice Biennale and have had solo shows at Stockholm’s Moderna Museet, the New Museum in New York, and, opening this month, in Shanghai, at Prada Rong Zhai.

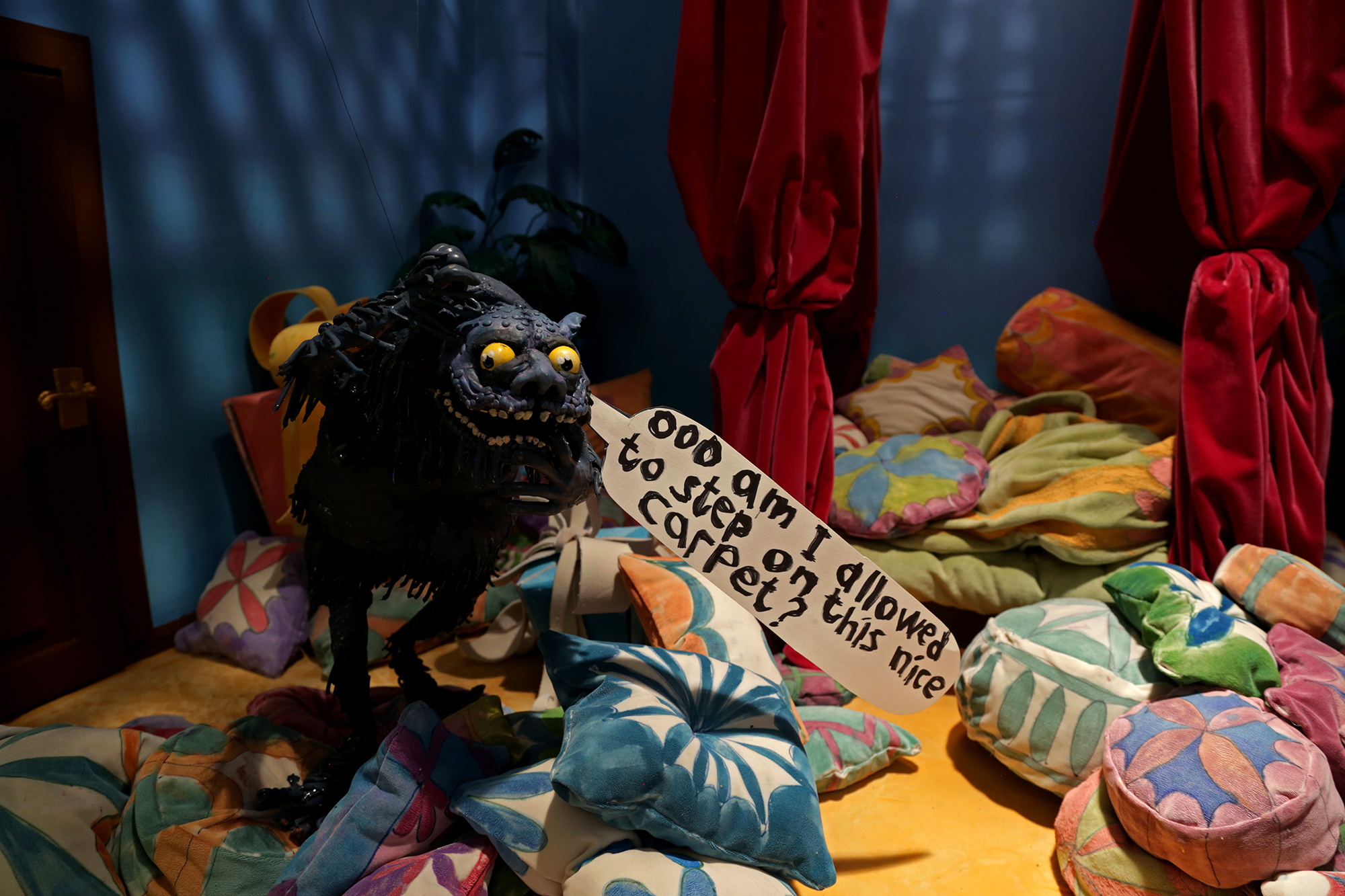

“We often forget that the white cube came at the birth of sanitation after the Spanish flu pandemic and the birth of modernism. Previously, salons were densely filled,” curator Lagos comments on her choice of venue for “Can’t Keep it in, Can’t Lock it Away.” She continues, “There is a sort of crescendo to how we invite the viewer into the space. It becomes a game of hide-and-seek as the works do not play in unison.” The setting, an ornately textured home environment illuminated by flickering candles and shaded lamps, is evocative, as many of the videos are set within interiors, specifically, rooms and hallways. The oldest work, The Prostitute (2008), installed above Livijn-Olin’s bed, is self-referential: it is about being an artist, says Berg, and “the fear of failure or getting hurt while exhibiting yourself for money.” In it, men grabb a lingerie-clad woman who is writhing seductively in a bed through a red curtain peephole.

Premiering in Stockholm, The Soft Spot (2021), installed in a small hallway leading to the bedroom, portrays a spindly man with a long Pinocchio style nose kneading the welts of a walrus. He greedily tries to grasp a pearl and a crystal, jabbing his long arm through a hole in the ice under the walrus. Leaning into imperfection, snippets of Djurberg’s hands manipulating her characters appear in many videos, however, in The Soft Spot Djurberg’s own hand kneading the walrus flashes across the screen purposely. I watch the video standing next to Berg, when he says: “A lot of it is up to interpretation.” I am assured that their work is best felt.

When we connect, Djurberg is attending to her motherly duties, “Do you feel embarrassed?” she asks referring to feeding, cooing and bouncing her two-month-old son on camera. “Of course not, I’m glad he came,” I respond. I am curious to hear if she will approach the body differently after the experience of pregnancy and giving birth. “Yes, everything that I experience comes out at one point or another,” she says. Her empathy has peaked; she chalks it up to hormones, but is grateful for her enhanced, “almost painful” sensitivity.

Motherhood has changed the way she relates to her work; she has a new reading of the 2008 piece, It’s the Mother. Initially, she created it thinking of herself as the child, recalling how “it described a longing and this frustration of wanting to merge again, but being rejected, and then being looked at.” Now, she can also read it from the perspective of a mother.

“You can never completely understand something until you have experienced it,” she says. “But, for you, Nathalie, ideas are often born from not understanding.” Berg chimes in. After a nod to Berg and a soft laugh she responds, “What I see, read, experience comes in through a funnel, and what does not pass through easily—things that create tension that I cannot let go of—seed an idea.” Berg concurs, describing it as, “things that nag us.” Animating bodies in clay is “clumsy,” Djurberg explains. “But it’s the crudeness that makes the characters open-ended,” Berg concludes.

Recently, the duo took a step away from physical molding and created a VR piece with London-based studio Acute Art. Though the process itself required some artist-to-programmer translation, the work provides “the most intimate viewing experience,” according to Berg. After all, the VR headset cuts viewers off from the outside world. The artists have also created a limited-edition sculpture for Avant Arte—a resin crocodile wearing permed wigs in a variety of colors. Berg and Djurberg speak fondly about their ugly crocodile who is desperately trying to look pretty. In 2020, they set the record for highest-selling work by living Swedish artists when another crocodile piece, Crocodile, Egg, Man, sold at Bukowskis for $1,908,983 (16,300,000 SEK).

Entering the world of Nathalie Djurberg and Hans Berg is taking a journey through the interior of the mind: a busy stage populated by characters and symbols that uncomfortably penetrate the lexicon of human emotion. Together, the pair are similar but also complementary and have managed to navigate the precarious act of breaking up romantically without breaking up professionally. Perhaps it is because, for them, one emotion trumps all. “Every work is about sympathy,” Djurberg concludes.

Craving more culture? Sign up to receive the Cultured newsletter, a biweekly guide to what’s new and what’s next in art, architecture, design and more.