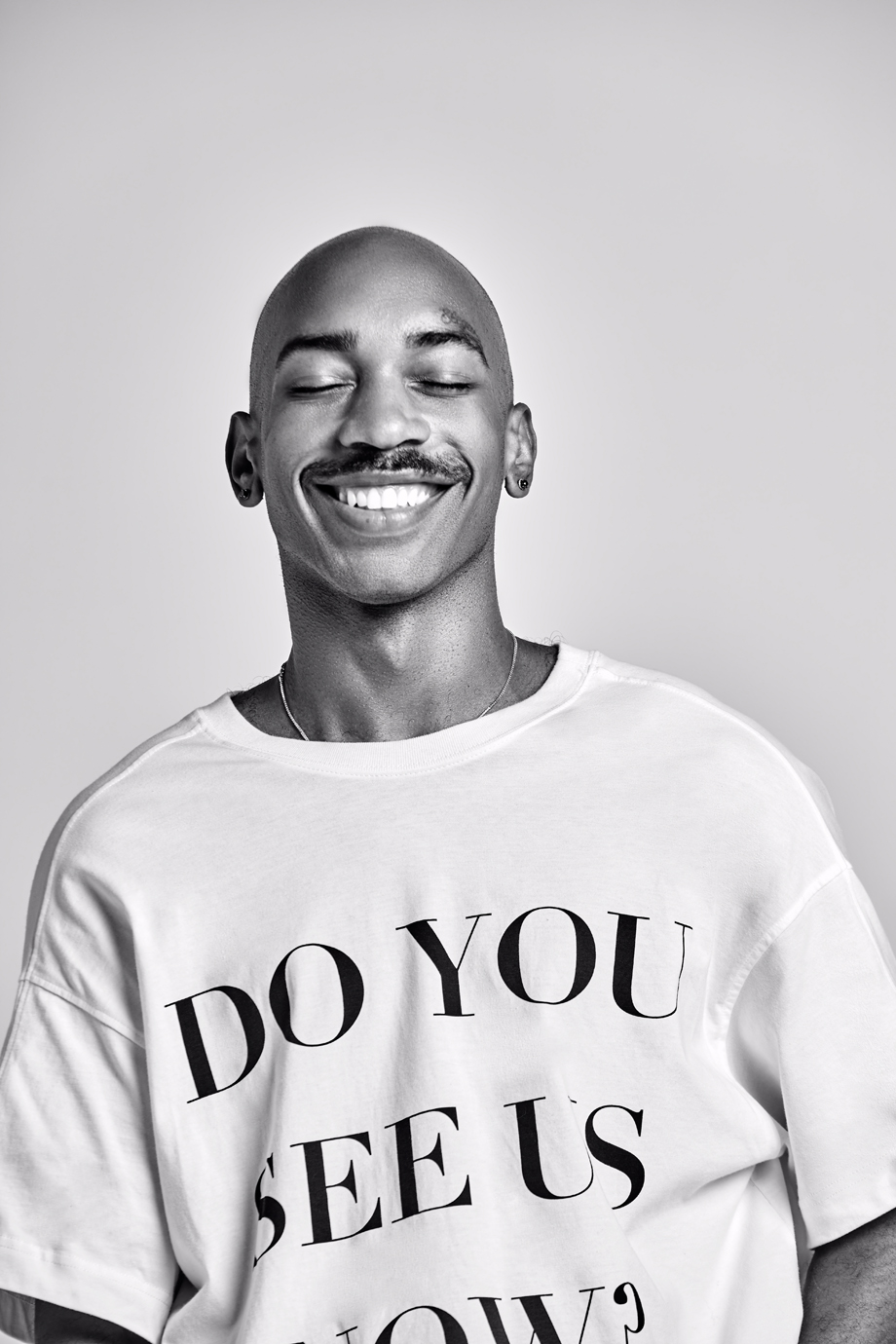

When asked about his earliest experiences with fashion, Antoine Gregory recalls the moments he shared with his grandmother, who worked for a furrier in New York City’s Garment District. On the weekends, he would accompany her on visits to thrift stores in the city, near his home on Long Island and in the Hamptons. His grandmother had an eye for fabulous things, and on these shopping trips they would come across luxury designers such as Christian Dior and Yves Saint Laurent. “That was my introduction to fashion,” Gregory tells me. “That was my introduction to luxury. That was my introduction to Black women being stylish.” He talks about his late grandmother with a wide smile, and although we’re speaking via Zoom, I can almost feel the warmth and regard he carries for her, and the impact she has had on his career and his commitment to Black people in fashion. Since graduating from the Fashion Institute of Technology (FIT) in 2017, he has blossomed into a multihyphenate, working as a stylist, director and consultant. He’s worked with some of the most coveted contemporary brands, such as Pyer Moss and Telfar, and in September 2020 he launched Black Fashion Fair.

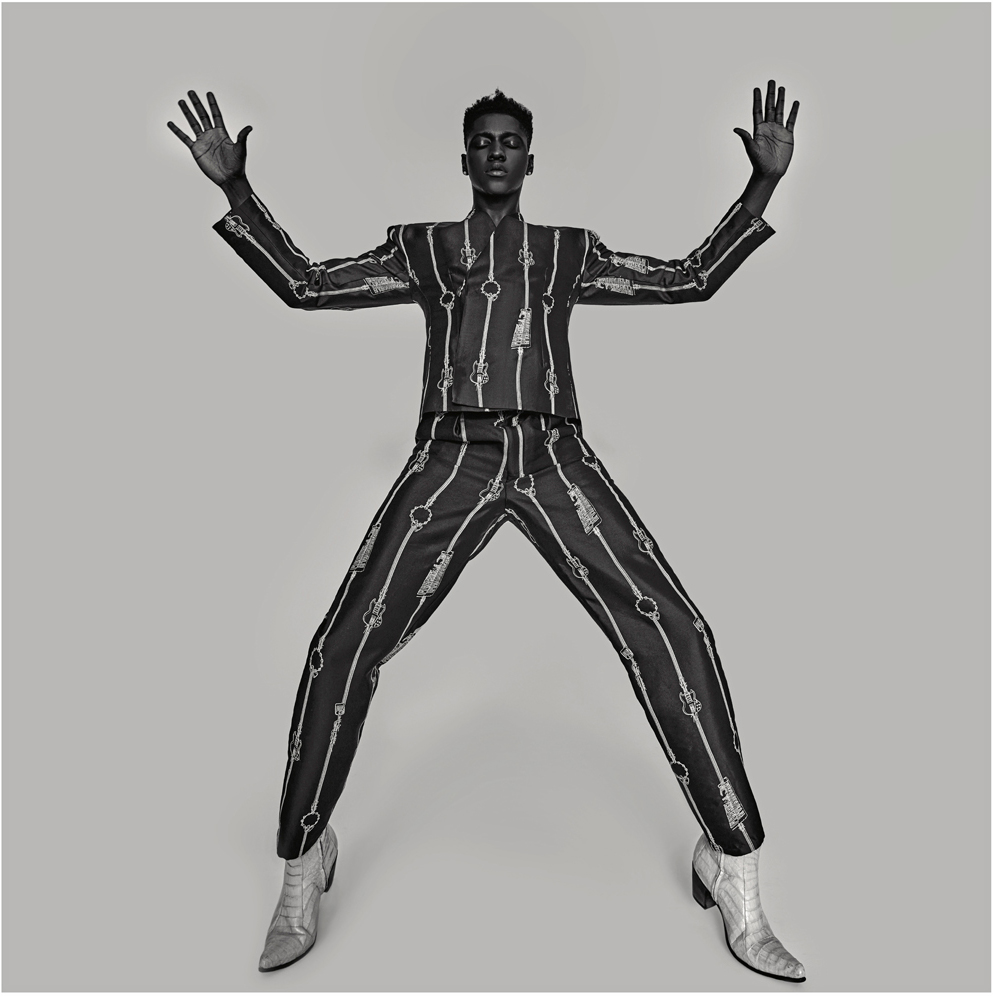

It all began with a 2016 Twitter thread, in which he listed Black designers that people should know, and grew into a mission to discover, support and further Black designers. Black Fashion Fair comprises of a first-of-its-kind, direct-to-consumer marketplace that sells products by emerging Black fashion designers such as Theophilio, Nicole Zïzi and Aliétte, plus a stories vertical featuring editorials and films styled by Gregory. Finally, there’s the directory, featuring about 250 Black designers past and present: from Ann Lowe, who designed Jacqueline Kennedy’s 1953 wedding dress, to Anifa Mvuemba, a designer who staged a 3D digital fashion show during the first wave of COVID-19 shelter- in-place orders. In 1953, Lowe’s name was omitted from the media coverage of the wedding; in 2020, Mvuemba was featured in Vogue’s September Issue. Gone are the days when the industry continually overlooks Black designers, photographers or stylists with the excuse that they simply don’t know of any. Gregory is making sure that you do.

Rikki Byrd: In 2016, you posted a thread of Black fashion designers. It was New York Fashion Week and you noticed that there weren’t a lot of Black designers on the schedule. What were the feelings behind you starting the thread?

Antoine Gregory: For me it was just how could I use the very small platform I had at the time to bring visibility to Black designers, because I’ve always kind of made it a mission of mine to support Black designers and wear Black designers and to discover them by any means. I went to FIT and I never once learned about a Black designer. And it left a really bad impression on me, where it was like, I’m going into an industry that obviously does not mirror me, that almost doesn’t even see me. How do I exist in this space when even at the educational level we’re not present?

Right out of college I got a corporate job and there were no Black people. I even interned at different companies and I would always be the only Black person, even at an interning level.

RB: What you’re speaking to as well is how fashion education is shaping the fashion industry. What we actually have to do is break apart this entire system, we have to explode this system to really address how we got to this point.

AG: I think fashion, like most industries, is reacting to what’s happening versus being progressive. So, now we see Black people being put into these positions almost just because. No one’s looking for affirmative action in fashion. Obviously, we need diversity, but we also need people in these roles that are qualified and can do the job and are passionate about what they’re doing. We don’t need to just put Black people in roles, so that in two years, you can put another white person in it and no one bats an eye. That doesn’t work. Like you said, we need to fully dismantle the system.

RB: So, let’s talk about your vision for how Black Fashion Fair can actually respond, rectify, recover—do a lot of work. You have said, on Twitter, “Black fashion designers are the future of fashion.” I would love to hear you talk about that.

AG: I think I’m so inspired by so many of the emerging Black designers like, Anifa [Mvuemba], Mowalola [Ogunlesi] and Kerby [Jean-Raymond], who’ve really ushered in this new generation of Black storytelling through design. So, when I say Black fashion designers are the future, that’s what I mean. Anifa did a 3D show during quarantine; when Prada did a similar thing, she was completely overlooked. She was the first one to do this in this type of environment, and to have her completely erased from that is the point of Black Fashion Fair. I wanted Black Fashion Fair to combat that happening to our stories and our people. I think Black Fashion Fair can be an institution like CFDA, like Vogue, like the British Fashion Council, because I’m doing this for the main purpose of documenting and preserving our history as it’s happening. I think that’s the greatest part about it. How many times do you want to reference something that’s so clearly Black but you cannot find where it came from? How many times was I trying to do an editorial, make mood boards, and I wanted to reference Black editorials, but they did not exist? They did not exist in a place that I could find them. So, what I’m trying to do is build that database, so when you want to reference a Black editorial or Black designers, here’s so much of it and you can take whatever you want, and it’s free.

RB: Can you talk about the importance of community to you in this project?

AG: I would not have been able to do Black Fashion Fair in the way that I did without the community of my peers, without being able to say, “Kerby, I need this collection from you.” I remember calling Jason [Rembert] and I said, “Jason, I’m doing this thing. It’s really important to me. Do you mind designing a product specifically for Black Fashion Fair?” And just like that, he did it. Just to have people like Ahmad Barber and Donté Maurice, who were the first Black photographers to shoot a cover of InStyle, to shoot a cover of Town & Country, to shoot our first fashion story. That’s important because not only am I giving visibility to these photographers, they’re giving it back to me, too.

We launched the fashion fair portion, where we sell only Black designers: all that money goes back to Black designers. I think giving people direct access to these designers was super important because you can go into a Bergdorf, you can go into a Saks and you won’t find Black designers. You may find one or two. I put, I think, 21 Black designers together. If I was able to do that, Saks should be able to do that, Nordstrom should be able to do that. So, when you walk into those stores and you don’t see Black designers, it’s a choice that someone made not to carry Black designers because they are clearly available, they have the product, and I sold a lot of it, so I know that people are buying it.

RB: It’s necessary work. And, you just answered my next question about the fair side of it. What’s been your selection process for the designers that you’re choosing for that side of the site?

AG: Well, I wanted to choose designers that had really great stories, and not just everyone who had a ton of followers. It was about having a diverse group of Black designers. Nicole Zïzi does streetwear, but it’s recycled. She makes a beautiful denim jacket out of recycled plastics from Honduras and Haiti. She’s a Haitian designer. That is a beautiful story. Jason Rembert’s brand Aliétte is heavily inspired by his mother and grandmother. That’s important to me. Pyer Moss, Fe Noel. Just like these beautiful Black stories that they tell through their clothes, it was super important to me to be able to put them all in one space and give people access.

RB: And people can learn about their work?

AG: Exactly. So even if you wanted to shop a designer, but you didn’t see a product that you liked, you can still go to the directory, go to their website and purchase from them directly.It’s not just about me having product to sell you, because, again, the designers are getting majority of the profits. Because of COVID and because of the climate that we’re in right now, a lot of brands are shifting to direct-to-consumer models. Historically, because Black designers have been left out of retail, they have always sold direct-to-consumer. So, here the industry is playing catch-up to something Black people have always been forced to do.

RB: Because of your interest in fashion history, what’re some of your favorite memories?

AG: André Leon Talley, I think he’s brilliant. I remember being in class, like, “Oh, I want to talk about André Leon Talley,” and no one knew what I was talking about. Everybody knew like Rachel Zoe. I think Pyer Moss’s spring 2020 show at Kings Theatre—that was a show that I immediately had a reaction to. It was beautiful to just see Black music and Black people and a Black choir. Reading Robin Givhan’s book about the Battle of Versailles. Christopher John Rogers, his last show [Fall 2020] was beautiful, brilliant.

RB: What’s next for you and what’s next for Black Fashion Fair?

AG: We’re working on our next fashion story, which will be an editorial and a short film. As Black Fashion Fair continues to advocate for greater access and visibility, these stories will document and preserve Black fashion and style. We’ll also be launching a designer capsule collection to highlight the designer’s story. Our first capsule is with designer Edvin Thompson of Theophilio. Our next Fashion Fair will take place this fall. I want to do an exhibit. I’m really excited about that. I’ve been having an idea to do this very specific exhibit for a long time, so I’m just hoping to find funding and grants and figuring that whole process out because it’s very difficult—I’ve put all of my savings into this project.

Craving more culture? Sign up to receive the Cultured newsletter, a biweekly guide to what’s new and what’s next in art, architecture, design and more.

in your life?

in your life?