Sienna Fekete: I wanted to begin with the start of the film, which opens with what one might assume would be the climax, the Mexico City Olympics, when Tommie decides to take a stance on an international stage. What was your impetus for opening the film this way?

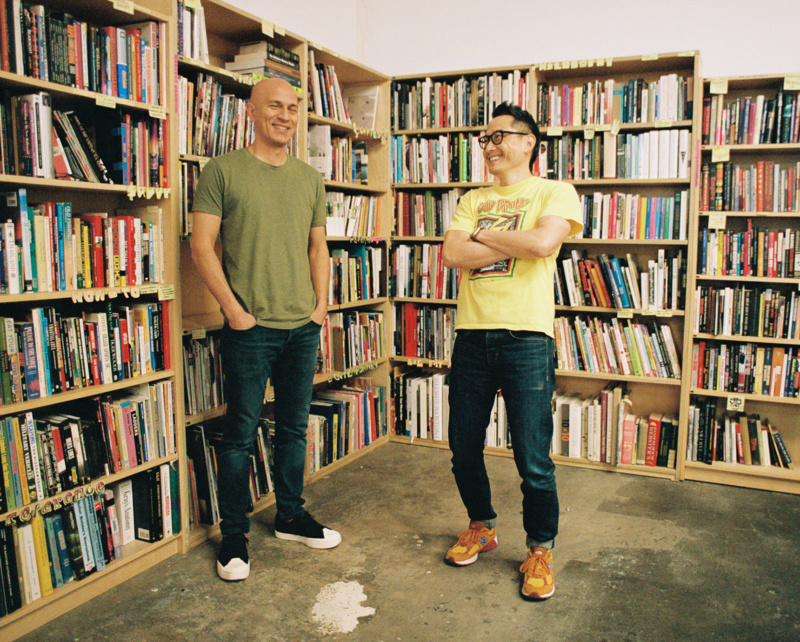

Glenn Kaino: I’d say Afshin and I started on this project years ago when we had no idea what the final format was going to be. We met Tommie under the auspices of just knowing there was a story to tell and wanting to tell it through art. Very quickly after Tommie and I started working together, I called up Afshin and we began to discuss making a documentary.

The process involved us eventually sitting down with hundreds of hours of our own footage, and what we knew to be thousands of hours of footage that Tommie had contributed to the media landscape over the past 50 years and stacks upon stacks of note cards. We ended up with the “aha” realization that Tommie’s own story arc matched the hero’s journey in how he aspired for greatness and then achieved it, but how his greatness almost became an adversary to his intention.

We didn’t have footage from the 1960s that we shot, but it was important for us to not have that period be covered in a way that was all talking heads.

The really big decision we made was to not have the film end with his salute, but to have it start with it. We wanted to say that the salute was something he did, but our film is really about the man and redemption. Not just for him, but redemption for society.

Afshin Shahidi: I don’t think I could say it any better. It’s a phoenix story. We never set out to make an archival or historical movie. We wanted it to be very much grounded in the present and Tommie’s activism and art now. As you saw, it starts with archival footage but after we establish his place in history, we move on.

SF: I’m very curious about the diverse cadre of artists you engaged in this film. What is the process like in working with these different actors, athletes, activists and journalists?

GK: I think this is where we were able to benefit from not being traditional documentary filmmakers.

AS: We didn’t have experts talking about this historical event in the way that other documentaries have. Nothing against that, but we intentionally decided we didn’t want this to feel that way. There were times where we questioned ourselves and asked if we should have someone, for instance, come in and speak about the symbol of the fist. So much of that we felt was already available.

GK: I think the landscape of expertise is changing too. For us, it was what is more credible: hearing about what it’s like to win a gold medal from a historian, or from Megan Rapinoe? What we were doing in the years before we were editing was actively connecting Tommie’s story to a new generation.

SF: You quote at the beginning of the film: “A single image has the power to change the world.” I think that’s true and I’m wondering about how this idea played into the retelling of Tommie’s story.

GK: Both of us being artists, we think about the value of what we do as image creators. I’ve always said that what art allows you to do is have a context for imagining alternative worlds. I have a utopic practice. It’s the job of the artist to imagine. It’s the ethical responsibility of those that are conscious to put forward imagery that has the power to inspire change. I think this is also very much the case in sports. Before Michael Jordan, no one had even thought about making a dunk from the free-throw line, and now it’s almost this rite of passage.

AS: The second half of the quote is really interesting. “A single image has the power to change the world by showing you something is possible.” It’s become such a piece of dialogue in terms of representation and changing the media landscape, both behind and in front of the camera. It speaks to what’s happening today and the attempts to diversify media, banking, the sciences—everything. SF: I see how your dynamic works, and it has me thinking about another scene that resonated with me. We see Tommie sitting in his den amongst his trophies and awards talking about his prolific journey. How did you cultivate the trust with him that this kind of filming requires?

GK: This was a multi-year process. Our first interview with Tommie came out of this artwork I was making. We got two hours on tape, but it was nothing special. It was the version of Tommie you get in every other documentary. We interviewed him again, and it got better, but it wasn’t awesome. And we kept repeating this, and while we are working on this film component, we were also flying around the world doing art shows and working on this education program for young kids.

Our friendships got deeper, including mine and Shahidi’s. And then a couple of years ago, we decided to really activate the film. We booked a dense week of shooting; most of the film’s footage comes from then. But mind you, this was after four years of knowing him and the pages of notes that I’d accumulated.

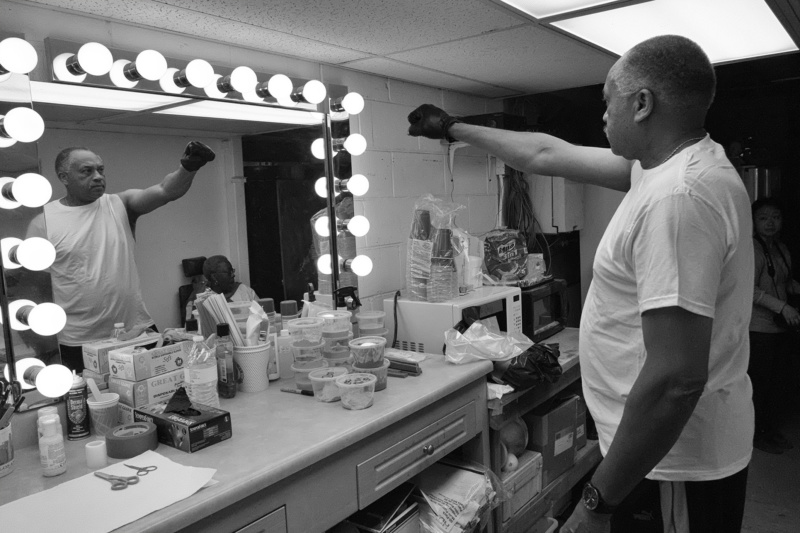

SF: I’m curious about the moment that comes right after one commits an act of defiance. In the film, journalist Jemele Hill speaks to the often-huge repercussions that occur after taking a stand against something, what late Congressman John Lewis calls “putting your body on the line” in an effort for change.

AS: I think that was a crux of the film. We felt that what everyone knew about that image ended with its taking. There is something that Jesse Williams said that I think is relevant: it’s important to jump. And what we need to do as a society is to catch that person when they do. SF: I would love to hear how the conversation around the significance of an individual gesture plays back into your sculptural practice.

GK: This whole project began with that inspiration in mind. As artists, we make work that enters the public and then has a dialogue with a viewer about meaning. As soon as a work goes into the public, I no longer have control. I’ve become very sensitive and humble and respectful about what it takes to be vulnerable and have ideas and make them real and then make yourself open to whatever they trigger in the world. So, when I looked at that picture and understood that I would have the opportunity to get the backstory, I thought: what an incredible opportunity to explore that generosity and use my own practice to make it resonate with a new generation. As students of history, these images become pages in a book. We wanted to make new works that allowed people to engage with these ideas now.

SF: Another big theme I saw emerging was the sense of legacy coming through the archival footage, the oral histories and later the physical objects that get added into the National Museum of African American History and Culture. To see Tommie work out with historian Lonnie Bunch what objects would be preserved is another form of history-making, and then to meet with President Obama about it!”

GK: Legacy has always been very important to Tommie. Tommie has led a life of humility and sacrifice. In making these works, we’ve learned how to think in a way that his legacy will be reflected over time. This took time. We are two main members of the legacy team now, and as part of that we knew that an important step was to archive the work at a museum.

To be able to use a historic moment like Tommie entering the Smithsonian as the context for President Obama to invite us into the Oval Office was like a bonus on top of a bonus.

AS: We wanted to make sure Tommie’s legacy went beyond 1968. He’s a three-dimensional human that contributed to this world far beyond this one moment at 24.