The tally of air purifiers that pocked “SYNC,” Carolyn Lazard’s Essex Street gallery debut in September, corresponded to manufacturers’ recommendations. If shown in the volumes of the kinds of institutional spaces where Lazard’s work often appears (Palais de Tokyo, Walker Art Center and the ICA Philadelphia, to name a few), their numbers would multiply according to square footage because it is, in fact, HEPA filter purified breeze blowing from the choir of haloed machine mouths that constitutes Privatization (2020). A new vision of the mundane, Privatization offers at once a moment of toxin respite and a blistering critique in the form of a premonition of urban miasma—infinitely worsened by climate catastrophe and a police force discharging warfare-grade chemicals against its people—becoming an impossible barrier to life. “The work started out as a gesture of goodwill,” Lazard reassures me.

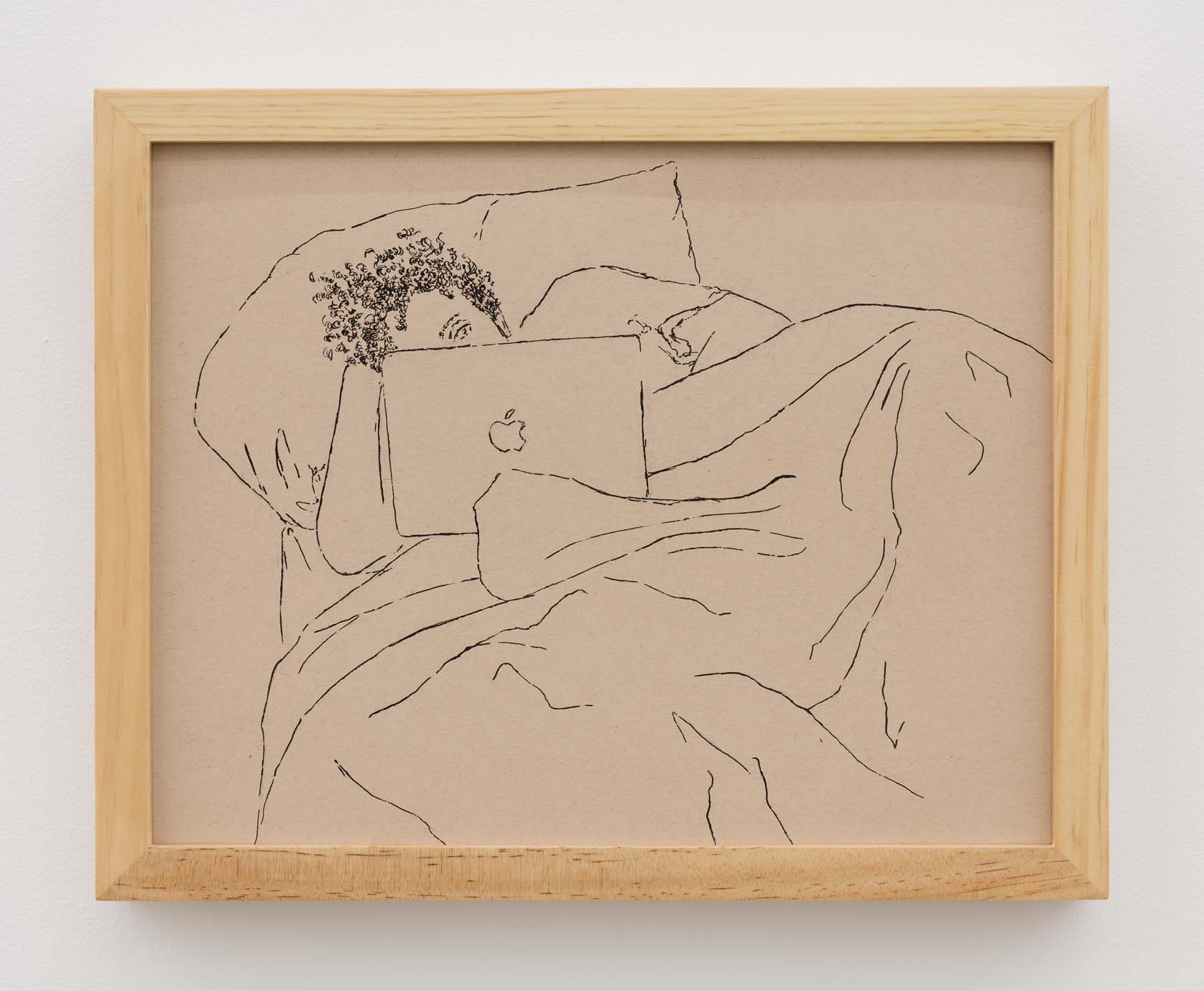

Though care for the viewer’s well-being permeates Lazard’s work, it doesn’t take away the edge of its appraisal. Lazard’s contributions as a writer, filmmaker and artist have knocked on the doors of institutions and individuals alike, to demand a fundamental overhaul of vision as it relates to our bodies and the demands we put upon them. Introducing the writings and work of crip artists to the public is central to this realignment. For “SYNC,” Lazard obtained permission to republish late writer and disability community advocate Tameka Blackwell’s And the Sun Still Shines because of the way the short story transforms the mundane into narrative complexity. “What we are told to register as an event in our lives is culturally and socially constructed, and some of the feelings and ideas behind the show deal with challenging this,” Lazard says. “Instead of hiding the temporality of the domestic, maybe we should have it be primary, and embrace the slowness of convalescence.”Questions surrounding America’s extreme discomfort with rest lay at the heart of the show, which transformed the white cube into a disjointed living room consisting of La-Z-Boys posing like figurative sculptures and a fleet of sinks moonlighting as televisions. Those indoctrinated in Lazard’s work might have expected video from the Philadelphia-based artist and, in a way, these metal and ceramic readymade basins filled that role, if only as screens for projection.