Life imitates art. Kaphar’s Jesus Noir (2020).

“As soon as I agreed to do the TIME cover, I immediately started to regret it. I didn’t think through how accessible I would feel,” Titus Kaphar confesses while seated on a stool, applying swift, careful strokes to the unfinished crowd in a basketball-related tableau titled Ascension IV on his studio wall. “I did not regret making the painting that is on the TIME cover or writing the poem that accompanies it,” he clarifies, eyes trained on the composition before him. “Those are real. I did regret how vulnerable I suddenly became, public in a way I’ve never been before.”

Based in New Haven, Connecticut, Kaphar has long ranked among influential and in-demand contemporary artists. A recipient of a 2018 MacArthur Fellowship, he surfaces racism by subverting the Eurocentric tradition. Colonial and Renaissance portraiture underpin Kaphar’s practice, with a restorative twist, reflecting the voices of people suppressed over and through those centuries of art and history. Famous for excising figures from a painting to focus on other characters in a composition—or to heighten absence—Kaphar’s work hovers between the second and third dimensions. Aesthetics, he’s said of his approach, often function like a Trojan Horse, beckoning viewers to open their hearts to difficult conversations about America’s racial past and present.

One of my favorite of his paintings, Behind the Myth of Benevolence (2014), reinvents a Rembrandt Peale portrait of Thomas Jefferson from 1800, to tantalizing effect. Forcing two images together through the motif of a drawn curtain hanging from its stretcher, the likeness of one of the most mythologized white men in American folklore is literally pulled back to reveal the partial image of a Black woman, leg and shoulder bared. Behind the Myth of Benevolence depicts Jefferson and Sally Hemings, he’s explained, and yet not; the woman also symbolizes all of the Black women erased by the founding fathers.

Indeed, throughout his career, Kaphar has unpacked the complexity and horror of American history. His works have entered the permanent collections of the Museum of Modern Art and the Yale University Art Gallery, among numerous others, and the National Portrait Gallery highlighted him in a two- person show in 2018. This fall, Kaphar celebrates two exhibitions: his debut with Gagosian, proclaiming a rare form of commercial success, as well as a show at Maruani Mercier Gallery in Brussels in October, for which he recasts classic religious motifs in his language of folded and crumbled canvas to defy viewers’ expectations of material space. In Jesus Noir, for example, a portrait of a young Black man is duct-taped over the face of Christ.

But Kaphar is right—the June 15th TIME magazine cover that presents his portrait, Analogous Colors (2020), vaulted him into another stratosphere of exposure and—though he would never say this himself—significance within wider culture. Analogous Colors depicts a grieving Black woman cradling the absent silhouette of her child, a harrowing reference to George Floyd calling for his mother as he was suffocated by the Minneapolis police. The issue included a special report on the nationwide protests over police brutality and systemic racism; and, in a first for the publication, TIME’s classic red border displayed text—the names of thirty-five Black Americans who were victims of racist killings. To accompany his illustration, Kaphar included a poem titled “I Cannot Sell You This Painting.” He writes, “This Black mother understands the fire. Black mothers understand despair. I can change NOTHING in this world, but in paint, I can realize her… This brings me solace… not hope, but solace. She walks me through the flames of rage. My Black mother rescues me yet again. I want to be sure that she is seen. I want to be certain that her story is told. And so, this time America must hear her voice. This time America must believe her.”

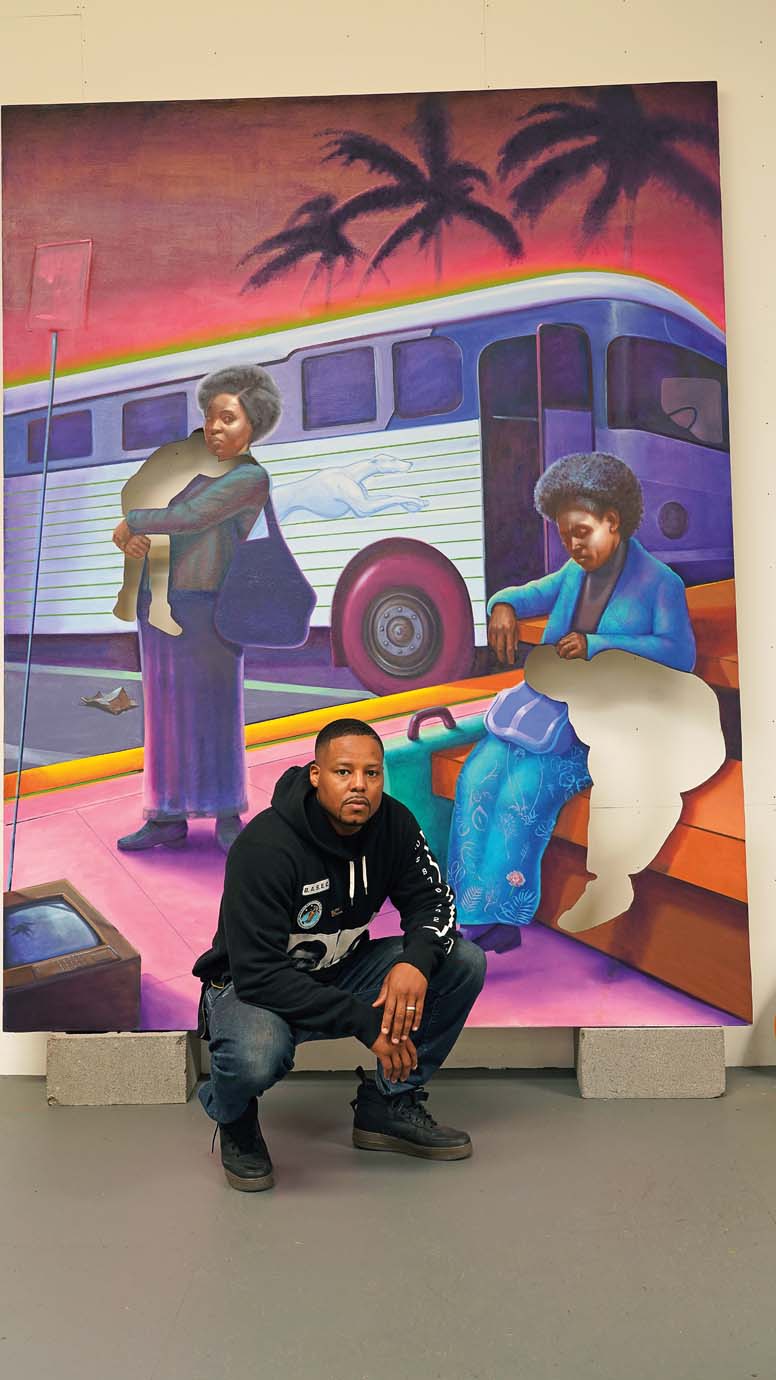

Kaphar poses with The Distance Between What We Have and What We Want (From a Tropical Space) (2019) in his New Haven studio.

Even before it hit newsstands, the cover ricocheted far beyond the art world, striking a chord on social media and news sites unlike any painting in modern memory. The number of participants suggest that the recent Black Lives Matter protests are the largest movement in the country’s history and Kaphar’s TIME painting, as it will likely come to be called, indelibly profiles America’s reckoning.

It’s been just over three months since I visited Kaphar as the first journalist to view his body of work “From a Tropical Space,” an apocalyptic series of images of Black mothers (including the original version of Analogous Colors) that unfolds in a surrealist Afro-future. Kaphar carves the children from each canvas by razor blade—a physical gesture of Black mothers’ enduring anxiety and trauma. Only weeks into lockdown, wearing masks and latex gloves, this in-person meeting felt like a minefield, as we were both unsure of the risk we were taking for our families. Early April seems like a different era: Derek Chauvin hadn’t murdered George Floyd; the country hadn’t yet erupted, millions of people taking to the streets with sorrow and rage at the incessant violence towards Black citizens. Now, I am back in his studio for this interview and to behold Analogous Colors in its current historic context. Of course, we are still social distancing, but a beleaguered normalcy has settled as the pandemic grinds on.

“Analogous Colors was already here when you came in April, but I was at the stage where it was still wrestling with me and I with it,” Kaphar tells me. “My process always begins like this: me trying to force my will on a painting that won’t submit.” He adds with a slight laugh: “For some insane reason, I must go through this again and again, before I realize that the only way for me to reach something truly articulate and poignant is to let the painting speak.” I suddenly grasp that the woman in the painting was someone else last spring, her anguish now deeper, eyebrows more angled, creases at the bridge of her nose like folded fabric. Observing her visage alongside the other paintings, she now expresses the sharpest pain of any mother in this series. “I was going through this process when George Floyd happened,” recalls Kaphar. “There were many sessions where my furrowed brow was mirroring the furrowed brow on this mother. I felt like she was going through my frustration and anger with this country beside me, or I was going through it with her.”

Kaphar at work on Ascension IV (2020).Then he got the phone call from TIME, requesting that he make another “hands up, don’t shoot” painting in response to the nation’s convulsion, similar to Another Fight for Remembrance (2015), the piece he created for the magazine five years ago, in his signature whitewash, to capture the impact of the Ferguson protests. He has since characterized this work as not not about Ferguson, but also not not about Detroit or Minneapolis. The title speaks to the repetition of police violence against Black men and women. “I told them absolutely not,” Kaphar says of TIME’s initial concept. “I don’t want to repeat myself. I’m not going to take my brush and articulate your idea.” He did, however, have a painting he’d been wrestling with. The rest—perhaps never truer than here—is history.

I ask Kaphar about how it feels to join those rare artists—like Ai Weiwei—whose work captures a seismic moment in time and compels such a deep reimagining of a country’s injustices that it transcends art history and manifests a larger collective consciousness. “Let’s be honest,” he answers. “The reason you’re making the distinction between history and art history is because by and large, what happens in art history doesn’t have a direct impact on real people’s lives. Picasso’s Guernica is an important work of art about a serious event. But if you stopped people on the street, how many of them would know the painting?” In contrast, he details the vast scope of art in the internet age, particularly amidst a social revolution—emails he received about the TIME cover from young people in Syria and Iraq.

A single message stands out: “A woman, whose name I won’t share, emailed me this beautiful text about her Black son who was murdered,” he describes softly, his voice laden with respect and compassion. “She said, ‘I’ve been looking for an image that represents my loss for years. I didn’t find one until your painting.’” When a work of art generates that kind of emotion, he says, a kind of alchemy or sorcery transpires; the two have corresponded quite a bit since. “Even though I feel like I was way too vulnerable, even though I feel too much on display,” Kaphar explains, “that one email made it clear to me: this was what I was supposed to do at this moment. Nobody else really matters.”

in your life?

in your life?