As the fashion world comes under greater scrutiny over the diversity of its leaders, it is also important to take a closer look at the diversity of its ideas. With an oversaturated market and unsustainable collection schedule, the pressure is on designers to make work quickly and to prioritize commercial success, often at the cost of unethical and profoundly damaging manufacturing processes. But, how one decides to use one’s platform is telling, and these seven designers stand out from the pack. Using their clothes, runway shows and activist platforms, they are leading fashion industry change by example.

“Kerby is adamant about not confusing the definitions of activism in relationship to him or his brand,” wrote artist Sable Elyse Smith about the designer behind Pyer Moss, Kerby Jean-Raymond, for Cultured in 2019. “So, the beauty here is the people he decides to feature, the people offered a moment to speak and share their concerns, dreams or experiences.” And his work certainly has proved (sadly) to be ahead of its time; in light of intensified momentum for the Black Lives Matter movement spurred by police brutality, the fashion world has been reexamining his S/S16 runway show from 2015, which opened with a 12-minute-long video on the subject.

“It has been clear for 20 years that prevailing iterations of identity politics were not subverting the fashion industry, but rather lending it content and credibility,” wrote Isabel Flower in 2018, in a profile of the gender-nonconforming fashion label No Sesso, founded by Pierre Davis. “With a different kind of authenticity in mind, Davis and her peers are insisting on working with and designing for their own communities. They are redefining the terms of and the relationship between fashion, art and popular consumption… This means looking for alternatives—alternative ways of dressing, alternative communities, alternative measures of success.”

“It’s not for you—it’s for everyone,” is the motto of Telfar Clemens’s eponymous brand, and he really means it. In addition to making a label of entirely unisex clothing long before the trend, Telfar also gives back by using its products to raise funds for social justice initiatives like the Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights Fund. “Telfar’s particular success is not so much the result of Clemens’s savvy attention to market forces and cultural whimsy but rather of his distance from these things, and his willingness to play with the industry’s conventions, expectations and biases,” wrote Flower in 2018. “In a direct-to- consumer world, without season, without gender, without designated arbiters of taste, the line between art objects and fashion pieces continues to blur as clothes shed many of the identifying features once used to demarcate garments and inject them with meaning.”

Raffaella Hanley’s clothing line is both science fiction and fantasy, the result of re-used fabrics with couture-level detailing, and a new model for sustainable fashion design. “Like the early collections of Martin Margiela, Hanley doesn’t limit herself to discarded bolts of material. She alters preexisting pieces she thrifts—approaching each like a problem waiting to be solved,” wrote Kat Herriman for Cultured in 2018. “The final garments are all but completely unique, making production almost impossible to scale especially from the artist’s improvised atelier—a small bedroom outfitted with clothing racks, a loom and a desk.”

Fashion designer Vejas Kruszewski, the youngest-ever winner of the LVMH Special Prize, revels in the art of allusion. His innovative work references film, culture and art, but subtly, and that subtlety sets him apart from his peers and models a different kind of creative exchange. “Kruszewski’s work is a prime example of how technical referencing is very different from thematic referencing; it adheres to a design sensibility grounded in construction as opposed to exoticism,” wrote Eugenie Dalland of the designer for Cultured in 2019. “It also shows how a specific kind of copying is not only a positive thing, but a necessity for innovation.” Said Kruszewski, “There might be some element I like in a garment, but I can only focus on that one part, zoom in on it and combine it with something else.”

Peruvian-born designer Mozhdeh Matin laments the fashion world’s failure to appropriately value textiles, so she amends it herself. Working directly with a manufacturer in Peru, to whom she gives a large degree of creative license, her garments use traditional Peruvian techniques that are at risk of being lost as younger generations pursue more modern occupations. Her approach is unique in an industry where the increased number of collections per year puts intense pressure on designers to produce quickly (and often unsustainably) for the next show. Wrote Dalland for Cultured, “Placing greater creative, emotional and social value on clothing design and manufacturing provides a model that could help designers—and, indeed, creatives of all fields—navigate the creative process in a way that positively engages everyone involved.”

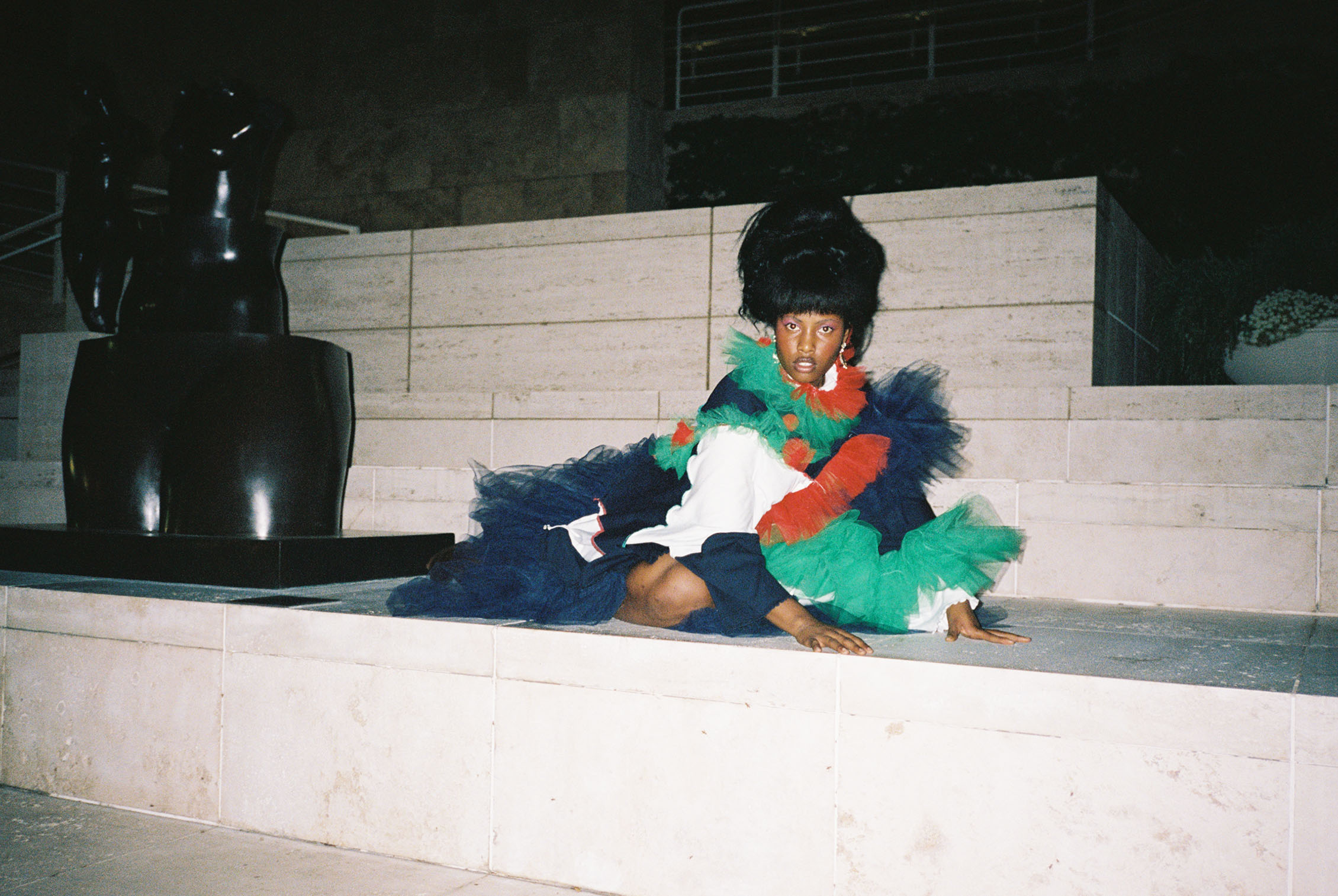

“I never really waited on anyone to validate what I was doing,” said Shayne Oliver, founder and creative force behind avant-gardist streetwear label Hood By Air, to Cultured in 2017. “It’s never really been about trying to be a fashion brand for me. When we began to evolve into the world of commerce, fashion was just a way of cataloguing the ideas we were putting forward.” His angular, genderless clothes hang on the body expansively, and are influenced by the styles of many of his friends; Boychild and A$AP Rocky have both walked the HBA runway, and artist Egon Schiele is an aesthetic inspiration, says Oliver. Following a hiatus that began in April of that year, he recently announced plans to relaunch the brand, on his own terms.

in your life?

in your life?